Last updated: July 11, 2023

Article

Equalization Schools of South Carolina

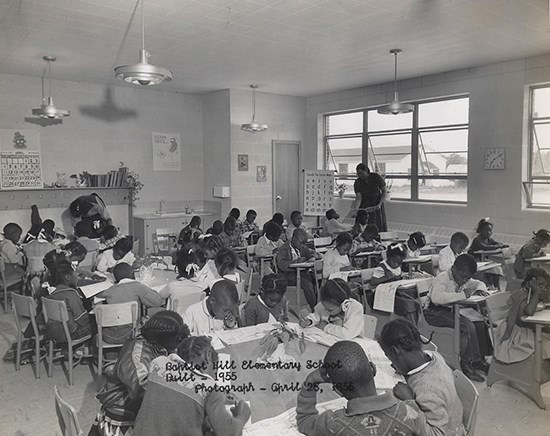

Photo courtesy of the Charleston County School District, Archives Department.

From the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation.

The state constitution that South Carolina adopted in 1895 mandated racial segregation in public schools. In 1896, the Supreme Court of the United States decided that it was constitutional to separate black and white Americans in public places. The court's idea was that racial segregation worked with American ideals as long as everyone received the same kinds of public services. This meant that if a water fountain in a courthouse was 'whites only,' then the local government had to provide a water fountain for Americans who were not white, too. This also meant that if a state or a local school board built a school for white children, they were bound by the U.S. Constitution to build a school for black children. This "separate but equal" policy supported racial segregation in the United States for over 50 years.

South Carolina used this policy in its public school system. However, while schools were separate, South Carolina never made sure they were equal. In the late 1940s, South Carolina spent $221 per white student versus $45 per black student in its schools. Outside of South Carolina's cities and towns, many African American students had to walk ten miles or more to get to school.

African American parents in South Carolina wanted their children to have the same services and schools with the same quality as the white children. In Clarendon County, a rural county in South Carolina, Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine led the parents' efforts to make this happen. DeLaine was a local pastor and teacher at Liberty Hill Elementary School. He worked with local parents and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1947, DeLaine and the parents group sued Clarendon County School District #22 and asked for a bus for black students. The court dismissed the case based on a technicality, but the parents did not give up.

DeLaine and the local parents decided to sue again. This time they sued in a federal court, not a state court. The lawsuit they filed is called Briggs vs. Elliott. Briggs was the last name of several of the African American children named in the lawsuit. Elliott was the last name of the chairman of the Clarendon County School Board #22 Board of Trustees. This 1949 lawsuit listed the differences between the white Summerton Graded School and the black Scott's Branch School. For example, the Scott's Branch school had outdoor toilets, wells for drawing water, old books, and stoves for heating. Summerton Graded had smaller class sizes, indoor plumbing, and new textbooks. This case was heard by the U.S. District Court in Charleston, South Carolina. The District Court had three judges. One of the judges was Judge J. Waites Waring. Judge Waring told the NAACP to sue for school desegregation instead of for "separate but equal" schools. Because of this, South Carolina's Briggs v. Elliot became one of the first desegregation cases in the United States.

South Carolina's new governor, James Byrnes, responded to the lawsuit with a statewide school construction program. The purpose of the program was to "equalize" black and white schools. This plan was in place by the time Briggs v. Elliott went to trial in late May 1951. During the trial, South Carolina's defense argued that it was already trying to provide "separate but equal" schools.

The U.S. District Court ruled in favor of the Clarendon County school district. However, the courts stated that South Carolina should be allowed time to equalize its schools. South Carolina was to give a progress report in six months. Judge Waring disagreed with the court's opinion. He wrote his own opinion to support the NAACP and criticize segregation:

“[S]segregation in education can never produce equality and that it is an evil that must be eradicated... the system of segregation in education adopted and practiced in the State of South Carolina must go and must go now. Segregation is per se inequality.”

"Per se" is a legal term, which means "in itself." Judge Waring was stating that he believed segregation can never be "separate but equal." It did not belong in a fair and just society. This was the first time since 1896 that a federal judge disagreed with the "separate but equal" policy.

The NAACP and the Clarendon County parents appealed the District Court's ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court heard Briggs as well as four other cases from Kansas, Delaware, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. These combined cases formed the landmark case known as Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the NAACP, stating that: "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." The Supreme Court used Judge Waring's dissent in Briggs v. Elliott when writing these words. Brown v. Board of Education overturned almost 60 years of legal segregation. This case was a victory for African Americans and the Civil Rights Movement.

Although South Carolina lost its case in Briggs v. Elliott, nothing changed immediately in the state. The Clarendon County parents who signed the lawsuit lost their jobs, homes, and land. Rev. DeLaine and his family left the state under a threat of violence. The African American students did receive new equalization schools, but remained segregated until 1963.

LEARN about South Carolina's Equalization Schools with the Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, Separate But Equal? South Carolina's Fight Over School Segregation.

VISIT places associated with segregation in education, including Brown v. Board of Education National Historical Park, Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, Crispus Attucks High School, and Rosenwald Schools including those at Cadentown, Kentucky, Catawba, South Carolina, and Finchville, Kentucky.

READ about Civil Rights in America, including School Desegretation, in theme studies by the National Historic Landmarks Program.