Part of a series of articles titled Disability History: An Overview.

Article

Disability History: The NPS and Accessibility

The National Park Service (NPS) strives to make its parks, monuments, and historic sites available to all. Programs, services, and products, such as Braille alternatives of print material, sign language interpretation of tours, accessible camping sites and trails, ramps and elevators make parks more accessible. These are essential to allowing the public to fully enjoy NPS resources. In 1979, NPS formally announced its intention to approach accessibility issues on a national level, rather than on a site-by-site basis. Since that time, the NPS has continued to improve its accessibility features, as well as create new and innovative ways for participation and inclusion. Described below is a small selection of parks that engage individuals with disabilities and share their histories.

Photo by Acroterion (CC BY-SA 4.0; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Camp_Greentop_MD1.jpg).

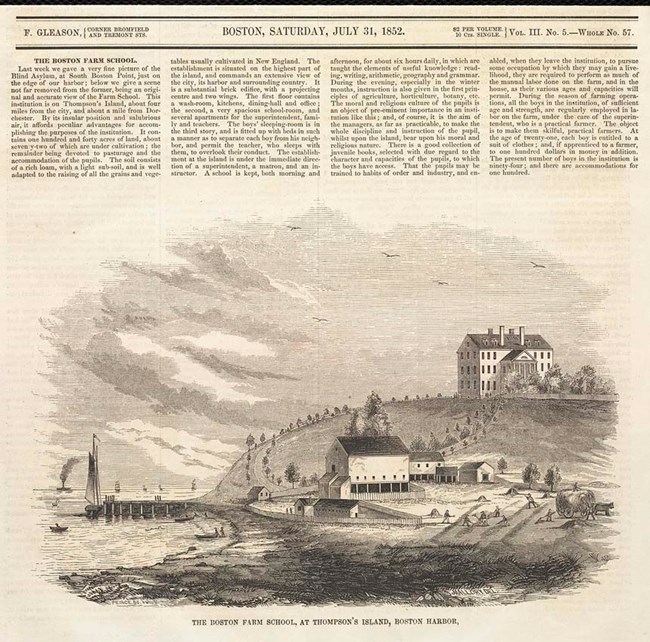

Since the early 1900s, camps and outdoor activity programs have existed for individuals with disabilities. Some of these services have been available at various national parks across the country. Though Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area was not established until 1996, the islands themselves have provided space for play and therapy for several decades. Thompson Island’s Boston Farm and Trade School assisted children with behavioral issues in the 1800s and early 1900s. In later years, managers of the island partnered with Outward Bound, an outdoor leadership program. Today, the organization encourages youth outdoor education in partnership with the National Park Service.

Similarly, children with disabilities have attended Camp Greentop since the 1930s. Camp Greentop is located in Catoctin Mountain Park in Maryland. In 1936, the NPS invited the Maryland League of Crippled Children to use their camp space. At that time, only 24 camps for children with disabilities existed in the US. This camp remains active today.[1]

Other national parks create interpretative programs for visitors that reflect on their own disability histories. Kalaupapa National Historical Park, located in Hawai'i, encompasses what was once a forced isolation center for individuals with leprosy, now more properly known as Hansen’s disease. Hansen’s disease is a contagious condition that affects the skin and nervous system. Until the 1940s, there was no effective medical treatment for the disease. From the 1860s until the 1960s, over 8,000 affected people were sent to this peninsula. In 1980, the National Park Service established Kalaupapa National Historical Park, encompassing both the isolation center and its surrounding landscape. Today, Kalaupapa National Historical Park interprets this troubled history for the public, as well as works with the local descendants and community to examine their past.

Harriet Tubman National Historical Park, located in Auburn, New York, and Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park in Church Creek, Maryland, show Tubman's dedication to public service over the course of her lifetime. Tubman is well-known as an abolitionist and “conductor” of the Underground Railroad. She helped dozens of families escape slavery and move to the north. A childhood trauma influenced Tubman’s decision to rescue others. Born into slavery, Tubman was attacked by a slave owner and received wounds to the head. This injury caused her lifelong seizures and narcoleptic episodes. She described these fits as visions in which she communicated with God. Tubman claimed these spells inspired her life's work to abolish slavery.[2]

Tubman, who lived from 1820 to 1913, eventually moved to New York State. Her work did not end there. She opened the Harriet Tubman Home for the Aged, where she also lived. This building served to shelter the needy and elderly. Many of these individuals may have lived with physical or cognitive conditions. Tubman’s lifetime of service is evidence of her willingness to help people of all abilities. After Tubman passed away, the Home for the Aged became property of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Today it continues as a museum honoring its visionary founder.

The National Park Service continues to improve its accessibility features. In 2000, the National Park Service released “Director’s Order #42: Accessibility for Visitors with Disabilities in National Park Service Programs and Services.” The Director's Order is the latest is a series of directives to staff. It explains why accessibility is a necessary feature of parks. Accessibility makes places and ideas easy to use and understand for the public. At the time of this order, the federal government required (and continues to do so under new ruling) accessibility in buildings and of programs. This order demanded that parks offer the highest level of usability. Facilities, programs, and services must apply universal design. Universal design is the concept that buildings, products, and space should be accessible to all. Services must be inclusive rather than separate or "special." With the report All In! Accessibility in the National Park Service 2015-2010 (.pdf), the NPS has continued to review its policies to effectively achieve this.

By making spaces inclusive, we can better understand our rich and complicated histories. The NPS helps tell a fuller story by including people with disabilities at their sites.

Article by Perri Meldon.

This article is part of the Telling All Americans’ Stories Disability History Series. The series focuses on telling selected stories through historic places. It offers a glimpse into the rich and varied history of Americans with disabilities.

Bibliography:

[1] Angela Sirna, “Tracing a Lineage of Social Reform Programs at Catoctin Mountain Park,” The Public Historian 38, no. 4 (2016): 167-189.

[2] Milton C. Sennett, Harriet Tubman: Myth, Memory, and History, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, 2007.

Last updated: October 31, 2017