Last updated: May 16, 2025

Article

Deconstructing the “out of sight, out of mind” thinking: why we must protect coral reefs

NPS / John Dengler

When walking through a forest with a designated trail, it is relatively easy to avoid stepping on animals or delicate plants. But in the ocean, humans swim amongst the animals and plants, leaving aquatic life vulnerable to impacts from human interactions.

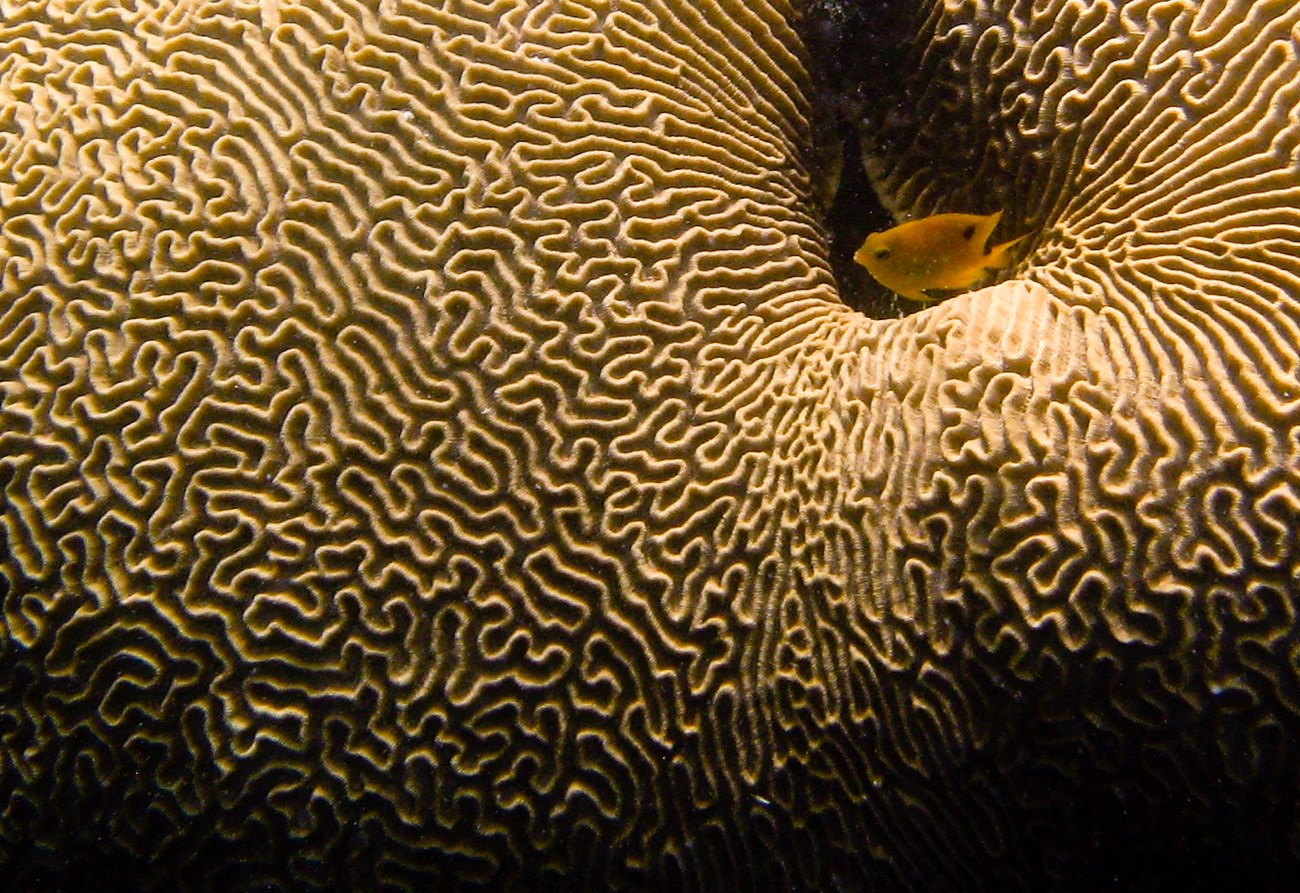

Adding to the challenges, some people may not be aware that some of the underwater objects they see are actually alive. Take coral for instance. Due to its sedentary lifestyle, rock-like texture, and plant-like structure, coral is often assumed to be just that, a rock or a plant. But like any animal, coral reproduces, eats, has a nervous system, and has a role to play in its ecosystem.

“If corals could scream when humans stepped on them, they would,” said Anna Toline, a former National Park Service (NPS) marine ecologist. “I don’t think people appreciate coral as a living organism when walking through a reef.”

Located just a short distance from most coastlines, coral reefs are often the victim of the “out of sight, out of mind” way of thinking, and the average beachgoer may not consider them in their vacation planning. From shore, when looking out at crystal clear blue waters, it is often difficult to consider what’s going on underneath. Thus, education is critical for their protection.

If you take a vacation to a tropical destination with coral reefs, such as ocean parks in the southeast United States, Caribbean, or Pacific Islands, consider the following and how to ensure your getaway protects coral and the ecosystems and services that rely on them.

What do coral reefs do?

Coral reefs are important, both as an ecosystem and to human livelihood. As one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, coral reefs provide habitat for 25% of marine animals while only covering a small percentage of the ocean floor. The reefs are breeding and feeding grounds for thousands of marine animals such as various fish, turtle, eel, shark species, and many more. When coral is harmed or removed from an ecosystem, the effects extend far beyond the coral itself.

Coral reefs are also important to humans. The fishing industry provides jobs for community members, cash flow in local economies, and a source of food for billions of people. The livelihood of many coastal communities depends on healthy, thriving coral reefs to support the fish populations upon which they rely.

Coral is also essential to the tourism industry, drawing snorkel and diving fanatics alike to marine national parks that provide these types of opportunities. If you’re more about lounging on the beach, though, you’re in luck. Coral provides physical protection to our sandy beaches, as their hard structure reduces wave energy by 97% and provides a barrier from storm surge and coastal flooding. As climate change continues to make storms more powerful, costal communities and tourists will continue to need to rely on their protection.

“Without corals, it’s a huge domino effect,” said Toline. “You don’t have coral, you don’t have fish, you don’t have tourism. It’s billions of dollars worldwide.”

To protect beach resorts, local ocean-front cafes, or your other favorite beach vacation activities, coral reefs need our protection.

What is happening to coral?

Coral reefs face a multitude of threats, including rising ocean temperatures. When ocean water gets too warm, microscopic algae (plants) that live in coral tissue are forced to leave. This algae gives coral its color but most importantly, they produce food for the coral. Byproducts of photosynthesis by the algae such as sugars help feed the coral. This is essential for coral growth and reproduction, and therefore, life.

When the algae leave the coral, the coral loses all color and turns white and frail. This event is referred to as bleaching. Bleaching can be devastating to the vibrant ecosystems and our world’s population of coral. While bleached coral isn’t dead, it does make corals more susceptible to disease or other stressors, and the prolonged high ocean temperatures or lack of algae can lead to die-offs.

“Recently we have seen an extreme bleaching event that has impacted coral reefs in national parks and all over the world,” said Jamie Kilgo, an NPS marine ecologist. “This event is due to some of the highest ocean temperatures recorded, especially in Florida and the Caribbean.”

Another major threat to coral reefs in national parks is Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD). The disease was first identified in 2014 and has rapidly spread throughout the South Atlantic and Caribbean. It is extremely lethal. Once infected, the coral will start to rapidly lose tissue, often leading to death. It is not yet known what causes the disease.

In addition to bleaching and SCTLD, reefs are facing threats from overfishing, ocean acidification, predation, invasive species, physical damage caused by marine debris, irresponsible recreation, and storm events. With a seemingly wide array of threats, it can be hard to determine what – if anything – you can do to help coral. But luckily, there are ways you can help!

This episode of Outside Science (inside parks) features researchers studying coral bleaching at War In The Pacific National Historical Park.

At War In The Pacific National Historical Park, the NPS Inventory and Monitoring Division gather data on the park’s coral.

What can you do?

It does not take an advanced educational degree in marine biology or ecology to save coral reefs. You can contribute to the protection and restoration of coral while on your beach vacation.

“It is important to think about how you can reduce your impact to coral and to recognize their vital role in supporting local communities and the marine life that live there,” Kilgo said.

Physical damage by visitors remains the largest threat to coral in national parks. Destruction comes from visitors walking on, kicking, or grabbing coral and boat groundings or anchors smashing them. The easiest way to protect the reef is to be aware of your surroundings.

-

When wading through the water, avoid stepping on the reef.

-

When snorkeling, especially with flippers on, avoid kicking the reef.

-

When operating a boat, stay vigilant of where the reef is so as to not run into it or drop your anchor onto it. Some parks may place mooring buoys nearby, which float on the surface to identify the reefs for boaters.

Minimizing this destruction can make a great impact on coral reef health and prosperity in national parks.

Additionally, many common sunscreens have chemicals that are hazardous to coral reefs (and, thus, the wildlife that rely on them) as they are washed off skin in the water. NPS scientists have detected high concentrations of these chemicals in park waters and are identifying ways to encourage the use of “reef-safe sunscreen” in national parks.

Remember, to prevent harm to coral reefs, it is best to use mineral-based sunscreens, not chemical-based. These will have zinc oxide or titanium dioxide as the active ingredients. Wearing protective clothing is another easy way to reduce the impacts of the sunscreen you use while also keeping you safe. Simple changes while on your vacation can make a big difference in coral reef health.

-

Keeping Coral Healthy

Keeping Coral HealthyLearn how you can help coral stay healthy.

-

Protect Yourself, Protect the Reef

Protect Yourself, Protect the ReefLearn how to choose sunscreens that are safe for coral reefs.

-

Pledge to Protect the Reefs

Pledge to Protect the ReefsJoin the community that is choosing to protect our ocean parks. Place a pin near where you live and pledge to protect our oceans.

What is the NPS doing?

The NPS and partners are using science to protect and restore coral reefs in national parks.

At Virgin Islands National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, both located on St. John, the NPS and University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) working hand in hand to grow coral in nurseries that will be placed in areas in need of restoration. With the nurseries, corals are sampled from colonies that have had success surviving warm ocean temperatures that led to bleaching events in other populations. The hope is that cultivating offspring from this coral, there is an opportunity to restore them to devastated areas and enhance the resilience of that populations. Partnerships are crucial to leverage work as much as possible, according to Toline.

“By working with partners like UVI, and also Coral World Ocean Reef Initiative, and The Nature Conservancy, we can identify how to address threats and increase restoration success,” she said.

NPS scientists are also responding to the threat of SCTLD, using an antibiotic paste to treat infected corals and studying corals that demonstrate resistant to the disease. Similarly to bleaching events, SCTLD outbreaks may be preventable when we understand what makes certain corals more resilient to it.

-

NPS Protects Coral from Disease

NPS Protects Coral from DiseaseLearn how NPS researchers are combatting Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease by applying amoxicillin paste to coral.

-

Stony Coral Tissue Loss in Florida

Stony Coral Tissue Loss in FloridaLearn how Dry Tortugas National Park is helping coral with Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease.

-

Coral in National Park of American Samoa

Coral in National Park of American SamoaLearn how corals off the coast of Ofu Island regularly experience extreme temperatures without widespread bleaching and mortality.