The Creeks turned to their traditions, customs, and spirits to defend their homeland against American expansion and aggression during and after the War of 1812.

By the early nineteenth century, American expansion threatened the cultural integrity and political independence of the Creek country, home to roughly 20,000 people of various Muskogean and non-Muskogean ethnicities and languages.

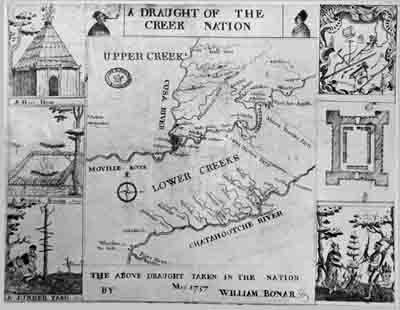

The National Archives, United Kingdom

In diplomacy with European, American, and Indian nations, Creek leaders promoted the concept of the “white path,” a metaphor for the path to the afterlife, for peace through diplomacy and in domestic life, and for the trails and rivers that connected towns (itálwa) and clans within and outside Creek country. This concept was the building block of traditional culture in the Nation, where medicine men healed the sick with aid from the Master of Breath (hisakitá misí) and knowers (kíthla) practiced their powers of clairvoyance and augury. Towns held the annual midsummer Green Corn Ceremony (póskita) that purified society.

By the early nineteenth century, American expansion threatened the cultural integrity and political independence of the Creek country, home to roughly 20,000 people of various Muskogean and non-Muskogean ethnicities and languages. An 1805 treaty led to the establishment of the Creek Federal Road, a horse and wagon path that ran through the heart of the Nation between central Georgia and Mobile. Increasing numbers of white families and their black slaves traveled on this road to the Alabama and Mississippi Territories. Between late 1811 and early 1812, more than 3,500 white travelers and black slaves passed through the Nation. Further, hundreds of illegal white squatters occupied lands beyond the Ocmulgee River, the official boundary between Georgia and the Creek Nation after 1805.

The Creeks fought back. Between 1812 and early 1814 Upper Creek “Red Sticks” organized a millennarian movement, led by prophets, along the Tallapoosa, Coosa, and Alabama River valleys that attempted to root out Creek leaders who favored adoption of American cultural norms, protested the loss of hunting grounds, and sought cultural renewal through mastery of the spirit world. On the Federal Road, some Red Stick men killed white travelers, while others obstructed the passage of the U.S. mail. Moreover, Red Stick warriors learned the “dance of the Indians of the lakes,” a spiritual import from the Shawnee prophets and warriors in the Ohio valley. Last, as the Red Sticks fled their towns and cornfields for the power and protection of the forests, the movement’s women increased their cultural role as food makers (hómpita háya) by gathering various roots and berries.

Although the Battle of Tohopeka (Horseshoe Bend) ended Creek involvement in the war in March 1814, Creek men and women adapted. Wealthy Creek leaders like William McIntosh and Big Warrior established and operated public inns on the Federal Road, while ordinary Creek men and women peddled sugar, meats, or coffee to American migrants and authorities in exchange for cash or goods in a nascent frontier exchange economy. Lower and Upper Creek towns still held the póskita. And hundreds of former Red Sticks continued to resist American expansion by establishing new towns and celebrating the póskita with their ethnic offshoots, the Florida Seminoles. In the late 1810s and early 1820s the Creeks forged ahead, adapting their culture and the world of spirits to the Southern postwar environment.

Last updated: August 14, 2017