Part of a series of articles titled Coastal Processes.

Previous: Coastal Processes—Tides

Article

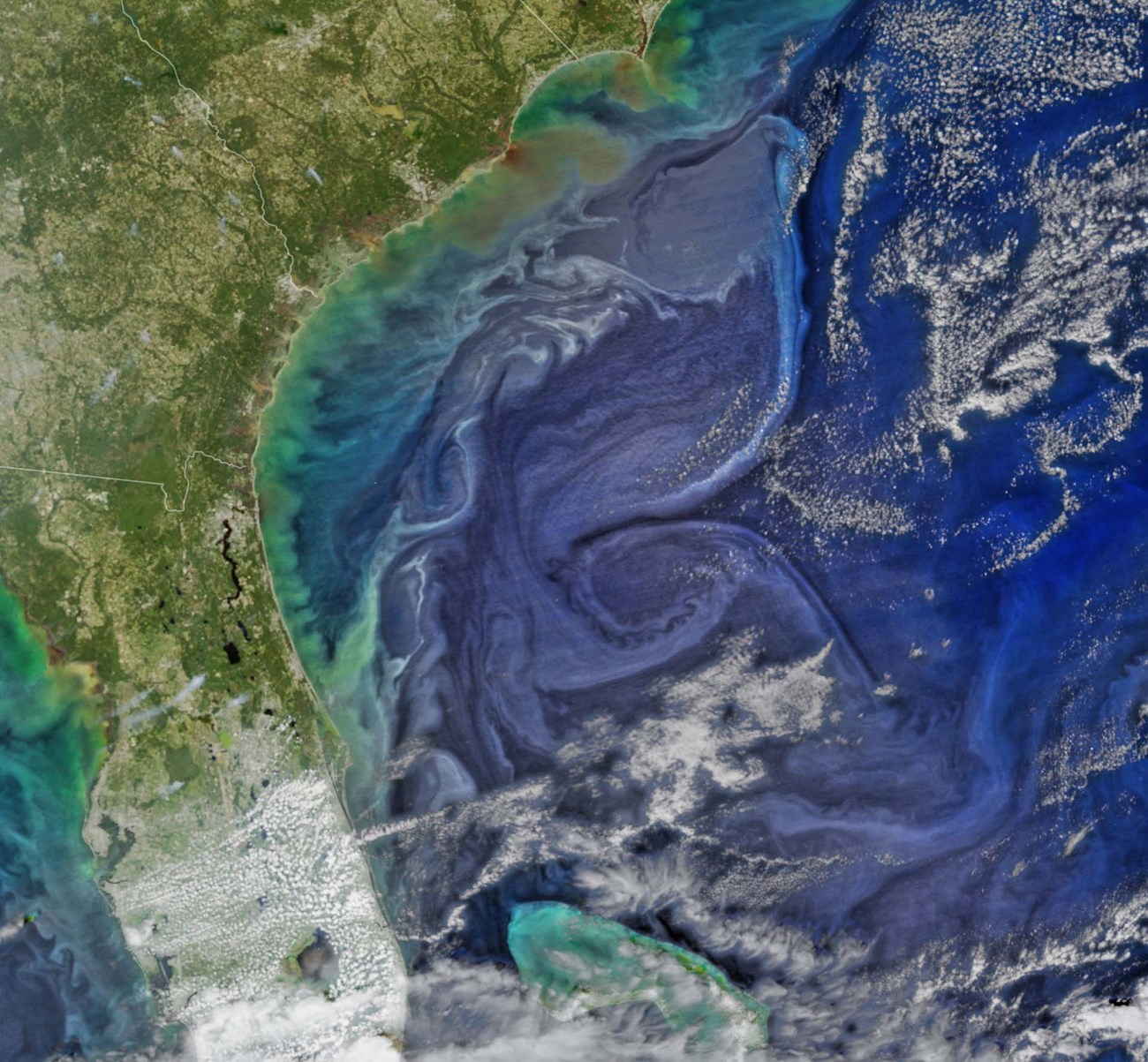

NASA/Goddard/SuomiNPP/VIIRS via NASA's OceanColor

The continuous, directed movement of water (or air) is called a current. Reflected, or turned back, by the beach slope, water from waves becomes undertow or cross-shore currents, flowing seaward. As cross-shore currents meet with incoming waves, some water spreads sideward and merges with other sideward-moving water. The combined waters form an elongated cell from which water flows seaward as a rip current, which extends to the so-called rip end, as much as half mile (0.80 km) offshore, where the water disperses in various directions. Rip currents disperse outside of the surf zone.

NOAA Photo.

Meanwhile, some water from undertow and incoming waves flow sideward parallel to the shore as longshore currents. These are created in part by waves meeting the shore obliquely. Longshore currents can be very strong; they can transport sediments and people along the coast. In areas with offshore mounds of sand, known as sandbars, longshore currents are often very strong in the trough that separates the sandbar from the beach. Longshore currents commonly feed into rip currents, mainly those on the downwind side. Strong currents are present at some park beaches. Learn more about dangerous currents to stay safe.

Waves are often known as the "shakers" of the beach environment. The motions of waves in shallow water act to suspend sediment, while currents move or transport the sediments. Currents associated with tides can transport and erode sediment where flow velocities are high. This is usually confined to estuaries or other enclosed sections of coast that experience semi-diurnal tides with a high range.

Part of a series of articles titled Coastal Processes.

Previous: Coastal Processes—Tides

Last updated: March 8, 2019