Last updated: April 19, 2021

Article

Climate Change Communication Series: Dr. Will Elder, Visual Information Specialist

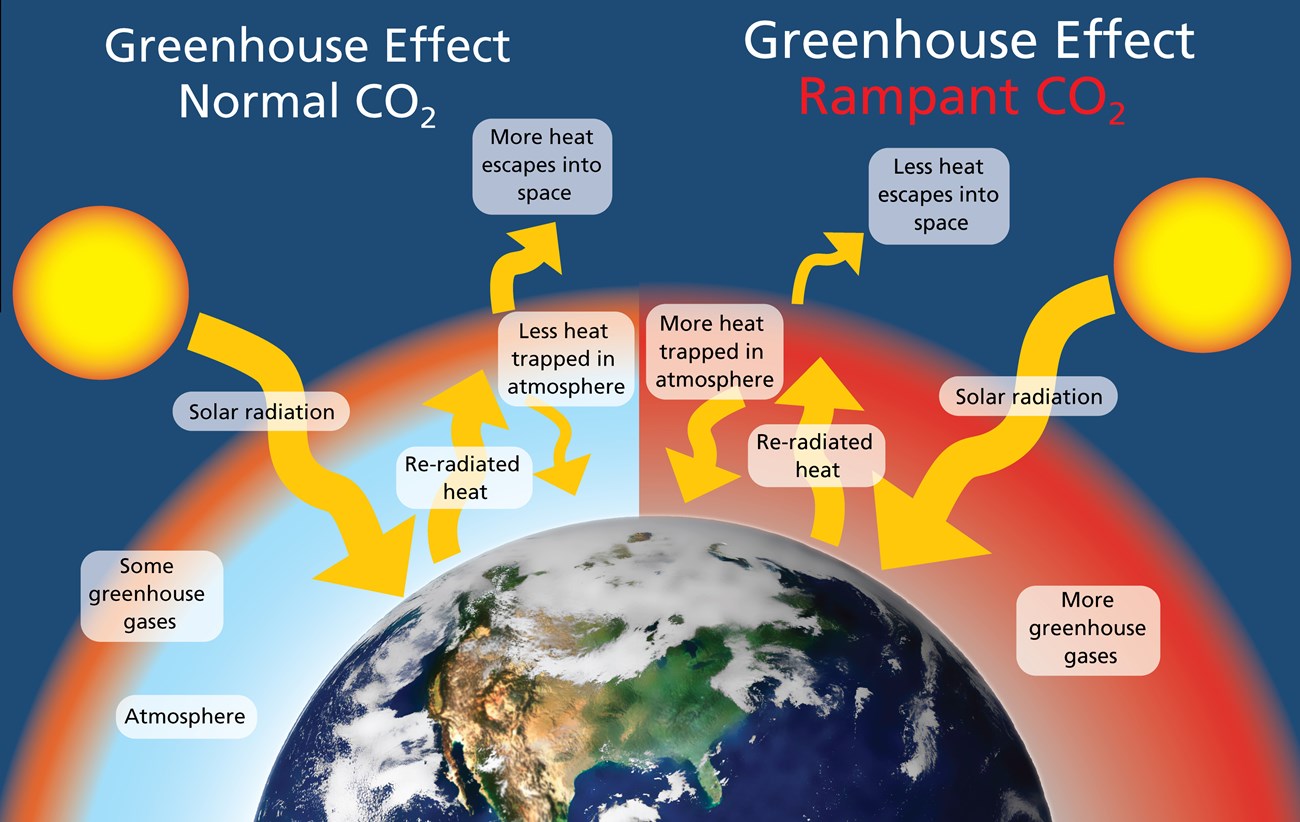

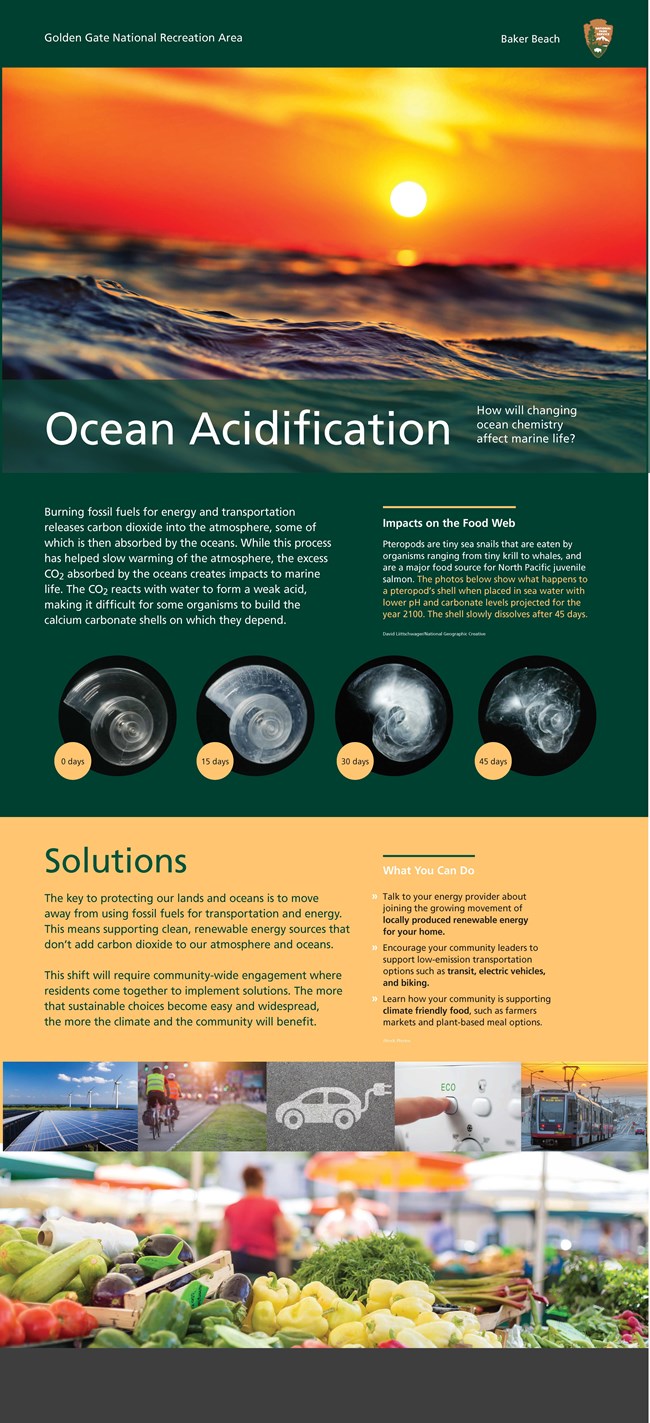

The burning of fossil fuels puts rampant amounts of carbon dioxide into our atmosphere. This results in global warming and other disruptive effects of climate change. National parks are subject to these effects even more than the US overall. While national park scientists document the trends and explore solutions, interpretive national park rangers communicate the nuances of climate change to the public. These separate roles can sometimes lead to a disconnect between scientists and communicators. How can we, as individuals or communities, use our understanding to help others increase their own climate literacy? Talking about it is a crucial first step. It can empower others to raise the topic of climate change in more settings.

Effective climate change communication is thus a vital tool for scientists, interpreters, and any concerned person working to enact change. In this interview, we dive into its strategies and nuances with Dr. Will Elder. Dr. Elder is a paleontologist and the media team lead for Golden Gate. As a visual information specialist, he also interprets the natural and human history of the park to visitors through exhibits, virtual content, and other media. Through conversations like these, we can work together to effectively convey the story of climate change. We can inspire ourselves and each other to work towards a common solution.

NPS

Can you elaborate on your background in climate science?

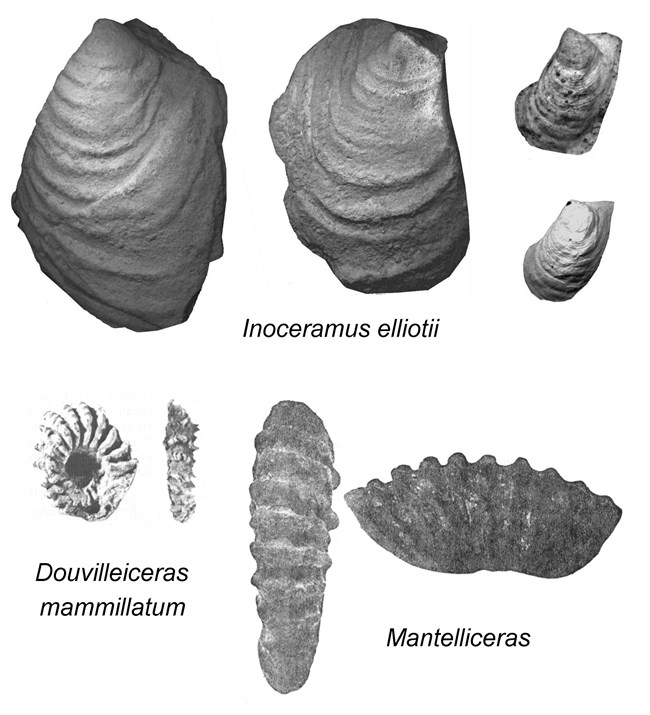

“I grew up in east Tennessee where there were a lot of fossils of various stages. My brother was a minor in paleontology in college, so we would go out and look for fossils. I learned a lot about Paleozoic history, and it was always in the back of my mind. I got my undergraduate degree in geology at UC Santa Cruz, and I went on to get a job with the USGS in Menlo Park doing geophysics. I did that for almost two years, and that was pretty cool. I applied for graduate school, and I was trying to figure out if I wanted to be a geophysicist or a paleontologist. However, I was never super good at calculus. But as it turned out, of all the schools I applied to, the one that gave me a scholarship was with a professor of paleontology at the University of Colorado Boulder. The professor I was working with was well connected with the National Center for Atmospheric Research. So my thesis evolved into studying the extinction event that occurred ninety million years ago. And of course, climate is always a suspect to major environmental events in Earth’s history. So that became a focus, and I got well-versed in all different ways of understanding climate change in the past – the far past. And I always continued looking at how we can understand paleoclimate through fossils.”

NPS

How has your background in paleontology and the sciences informed the way you approach science communication?

“It can be hard for me to get away from a hard science approach. So that’s a struggle; to make it a little easier to digest for people, a little bit more personally meaningful. I’m very detail oriented and it’s easy to get lost in the details. The way we want to portray things for people is by not getting lost in those complexities but simplifying things in a way that makes it really easy to grab onto. There’s a real balance of not leaving something out, or portraying something wrong, and I sometimes struggle to portray things in a really interpretive framework. In terms of geology, I’ll try to bring in uses of rocks that people understand. The household items; things that they can relate to a little more easily. But there’s just a lot of abstract stuff out there in relation to climate change. Attending various trainings helps me better understand social sciences, and the way that people learn and connect with things.”

In your opinion, what is most important for Golden Gate to communicate to the public about climate change?

“The idea that the park is protecting lands that have critical resources, and managing them in a way that helps build resilience to face current and future conditions. The ocean-atmosphere dynamics that we see here on the coast – the fog, the upwelling – is really telling of how climate change is affecting physical and biological systems at once. That helps our whole understanding of how the climate is acting.

And that actions can make a difference, and the park can help people understand community-level options that they can take. I think people need to hear there are things we can do to minimize some of the impacts.”

How do you see human narratives intersecting with the direction of climate change?

“I think we can talk about human adaptation to climate change over longer periods of time. This is a little indirect, but the earliest people living here were mostly living out near the shoreline thousands of years ago. And now the sea has risen significantly since then. So that’s one reason why many people think we don’t have a lot of evidence of those 8 to 10,000 year old communities. But we do know that indigenous cultures have been tremendously affected by climate change in the past. Yet they adapted – so there’s a resilience factor there.

But there’s no comparison to the climate before we had billions of people impacting the planet. Our impact is huge because of the number of people and the way we are supporting them. So externally, I think the human story is one of figuring out how we can live on this planet successfully.”

What role can urban national parks like Golden Gate play in addressing climate change? Do you think there are advantages and disadvantages in the way this park transcends urban and remote boundaries?

“It’s a double-edged sword. A traditional national park setting has a captive audience. Whereas here there are so many options for people to do things in the Bay Area, that they have a lot of other choices than to come to a program that may not really fit their mindset. But we’re also preaching to the choir here frequently. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. A choir can sometimes benefit from better understanding, or direction perhaps. Climate change communication can help those that may be panicking not panic so much. So there’s a big difference as far as audiences go than in a traditional park setting.

I think there’s a lot of opportunity in an urban park to get creative with programming. And you know, it’s always been a little uncertain to me what audience we can and want to attract in order to make a bigger difference. Because obviously the people that don’t want to change their mind at all are never going to change their mind. We probably want to contact the people that can affect the biggest positive changes. How do connect with that audience? I don’t know. But we definitely have the opportunity, because we have so many people nearby. It’ll take some work, ingenuity, and input from social science.”

NPS

What emotions do you feel when you look forward to Golden Gate’s future as climate change progresses?

“I’m optimistic that we will come up with ways to manage the park in a way that will increase its resilience and allow it to be a refuge for rare and endangered species. I’m optimistic that we will be able to keep some of these corridors open to other protected areas and enable things to move around successfully and survive. Which might not happen in other places. For example, I fear for the ability of Sierra ecosystems to survive the drought stress they’ve been going through. But I think we’re in a relatively good position here near the coast, perhaps to be a sort of showcase of how resilience and adaptation can work.”

Further Reading

Climate Change: Pacific Coast Science and Learning Center

Climate Change: National Park Service Subject site

Geologic Activity at Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Jobs and Internships at Golden Gate National Recreation Area

National Network for Ocean and Climate Change Interpretation (NNOCCI)

Interview by Lara Volski, August 2020.