Last updated: March 6, 2023

Article

A Century of Candelilla: Wax-Processing Camps in Big Bend National Park

NPS photo

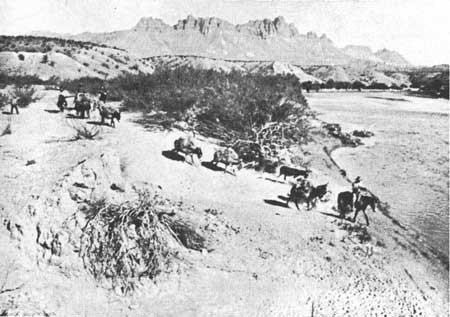

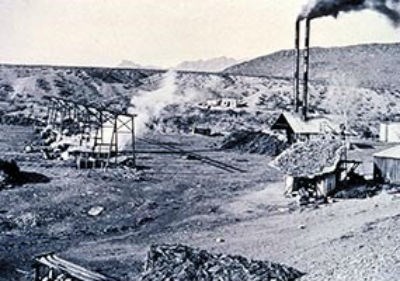

Candelilla is a flowering plant native to Texas, New Mexico, and multiple Mexican provinces. It has also been termed the “wax weed” for the natural, outer coating of wax that grows along its multiple, reed-like stalks. This wax is an ingredient for thousands of commercial products ranging from shampoos to furniture polish to chewing gum. Despite this wide usage, most of the candelilla harvesting and processing is done by laborers (most of whom are Latino) living in temporary desert camps and relying on their own hands and burro labor. Big Bend National Park contains the traces of many wax-processing camps. Because the candelilla industry is still active, some of these camps are recent. However, others are over 100 years old.

JoAnn Pospisil, Texas Beyond History

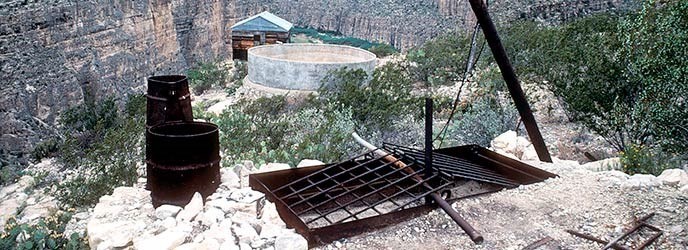

Although workers’ camps are transient, they leave their marks upon the landscape. As Curtis Tunnell noted, “the most prominent features…include vats and firepits, deeply work trails, piles of ashes, sleeping shelters, [and] cooked candelilla piles” (Texas Beyond History). According to Tunnell’s archeological and ethnographic research, processing areas within camps are often separated from living areas. The latter often contain ‘beds’ of plant piles, hearths, and other domestic remains. While many camps are open-air, laborers have also constructed dugouts or used rock shelters as additional protection from the elements.

NPS photo

Resources

Big Bend National Park, specifically the Glen Springs and Archeology pages. National Park Service.Casey, Clifford B. Soldiers, Ranchers and Miners in the Big Bend. Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation, Big Bend National Park, National Park Service, 1969.

Maxwell, Ross A. A Guide to the Rocks, Geologic History, and Settlers of the Area of Big Bend National Park. Guidebook 7. Texas Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin, February 1968.

Wax Camps along the Rio Grande. Texas Beyond History, 2004.