Last updated: December 16, 2024

Article

Words Have Power

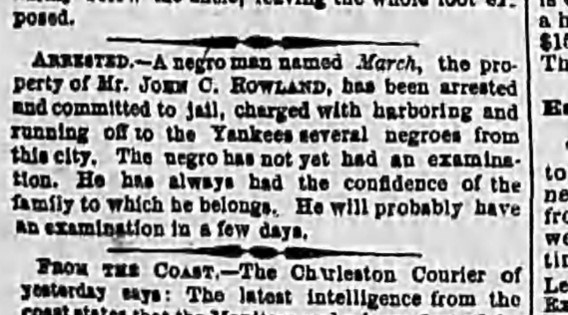

Daily Georgian 1836

Words Have Power

“A battle lost or won is easily described, understood, and appreciated, but the moral growth of a great nation requires reflection, as well as observation, to appreciate it.”-Frederick Douglass, 1864

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, few could have imagined the immense change that would emerge just four years later. At the beginning of the war, over four million people were enslaved and by the end they were free. A war that started with reunification ended as a war for freedom. The emancipation of the enslaved and abolition of slavery was not the end of the fight, however. Though free, equality was not a guarantee. The years following the end of the Civil War saw battle after battle in the fight for equality. In many ways, that battle for equality continues to this day.

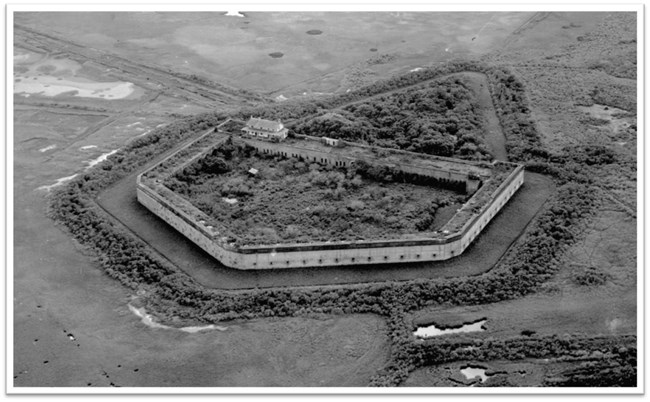

Building Fort Pulaski

Construction on Fort Pulaski lasted from 1829 to 1847. A third system fortification, the fort was built predominantly out of brick and mortar. An estimated five million bricks were used in the construction of Fort Pulaski.

Two different types of bricks were used in the construction: strong red bricks brought in by ship from Maryland and Virginia, and local grey bricks brought in from the Hermitage Plantation. Located three miles outside of Savannah, the Hermitage Plantation consisted of a sawmill, iron foundry, and a brick plant. It was at this brick plant that enslaved men, women, and children made the bricks that were used in the construction of Fort Pulaski.

Library of Congress

The Brick Making Process

Making bricks is a labor-intensive process. First, soil is thrown into a pit and mixed with water. Using their bare feet, the enslaved laborers would stomp the mixture into clay. Second, leaves, sticks, and debris must be removed from the wet mixture before being placed in a wooden mold. From there, the excess clay is removed by drawing a straight wooden stick across the top of the mold. Next, the wet bricks are removed from the mold and left out to dry over a period of several days.

Then the somewhat-dry bricks are manually moved to a drying shed where, protected by the weather, they continue drying for several weeks. Then, the bricks are yet again hauled from the drying sheds to a kiln. Inside this kiln, the bricks are fired and hardened for up to six days and nights. The bricks then must cool for around a week. Finally, the bricks had to be placed on wagons and then ships before arriving at Cockspur Island. From there, the bricks would be unloaded and hauled to the construction site.

NPS/Elizabeth Smith

Embedded in Brick

Throughout the southern United States, including in Savannah, it was against the law for an enslaved person to learn to read or write. Because of this, few written records were ever created, leading many to simply not discuss the history of slavery. Despite this, echoes of that story can be found in the form of fingerprints and handprints left behind in the bricks that make up Fort Pulaski.

Because the brick making process required the movement of many wet bricks, fingers and hands pressed into the bricks leaving behind these physical reminders. While the names of these people often went unrecorded, their legacy lives on through these glimpses into their daily lives. As you continue to explore the fort today, keep a close eye on the bricks. Look for these stories embedded in the bricks. Think about what it would have been like to make these bricks and to build this fort and remember that, though we may not know their names, we know these men, women, and children existed and they deserve to have their story told.

NPS Photo

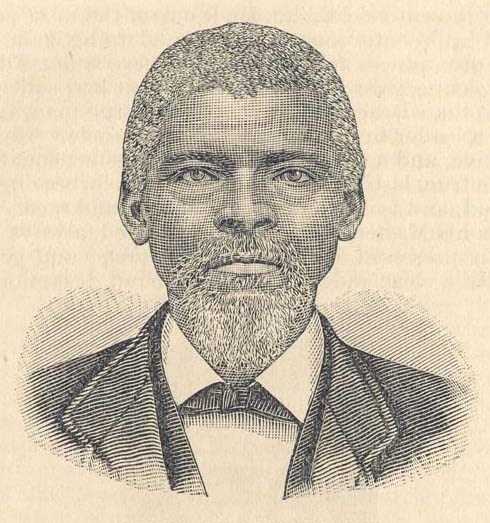

March Haynes

Born into slavery on March 4, 1825, March Haynes was brought to Savannah, Georgia, in 1858. He worked as a dock worker and a pilot on the Savannah River which allowed him to become familiar with the waterways surrounding the city. In 1861 he was brought to Fort Pulaski and his carpentry skill put to work. His knowledge of the waterways became useful to the Confederates who used him to deliver mail between the fort and the city.

During the bombardment on April 10 and 11, 1862, March Haynes remained at Fort Pulaski. When the Confederate garrison surrendered the fort, Haynes and several other enslaved people were left to wonder what would happen to them. The answer came on April 12, 1862, when Major General David Hunter issued General Orders Number 7, which read:“All persons of color lately held to involuntary service by enemies of the United States in Fort Pulaski and on Cockspur Island, Georgia, are hereby confiscated and declared free, in conformity with law, and shall thereafter receive the fruits of their own labor.”

Martin Pate

Freedom Seeker

With the United States in control of Fort Pulaski and the issuance of General Orders Number 7, March Haynes was a free man. No longer enslaved, he could have solidified his freedom by travelling further north, away from Savannah and his past enslavement.

Instead, he remained and assisted others held in bondage to take their freedom as well. At the risk of his freedom and his life, Haynes frequently traveled the waterways surrounding Savannah in a small camouflaged boat. With each return to Cockspur Island, he brought with him numerous freedom-seekers who escaped their enslavers and took their freedom on this island.

In total, several hundred enslaved men, women, and children found their freedom on Cockspur Island. While some remained on the island throughout the war, others travelled further north to the Sea Islands of South Carolina. For March Haynes, however, his job had only just begun.

Savannah Daily News

Spy and Soldier

With his knowledge of the Savannah waterways, March Haynes was invaluable as a spy for the Union army. Setting out on reconnaissance missions, Haynes and his team secretly located Confederate positions and fed the information back to the Union army.

These missions came to a halt in April 1863, however, when March Haynes was arrested in Savannah. A Savannah newspaper reported that he been caught in the act of “running off” enslaved people to the Union lines. This was a serious matter, one that would have surely ended in his death, but not a single person appeared at his trial to testify his guilt. As a result, he was released.

Soon after, Haynes left the spy business behind and officially enlisted in the United States Colored Troops. He was among the roughly 180,000 African Americans who enlisted to fight for the Union army to bring freedom for themselves, their families, and every other person held in slavery.

Nps Photo

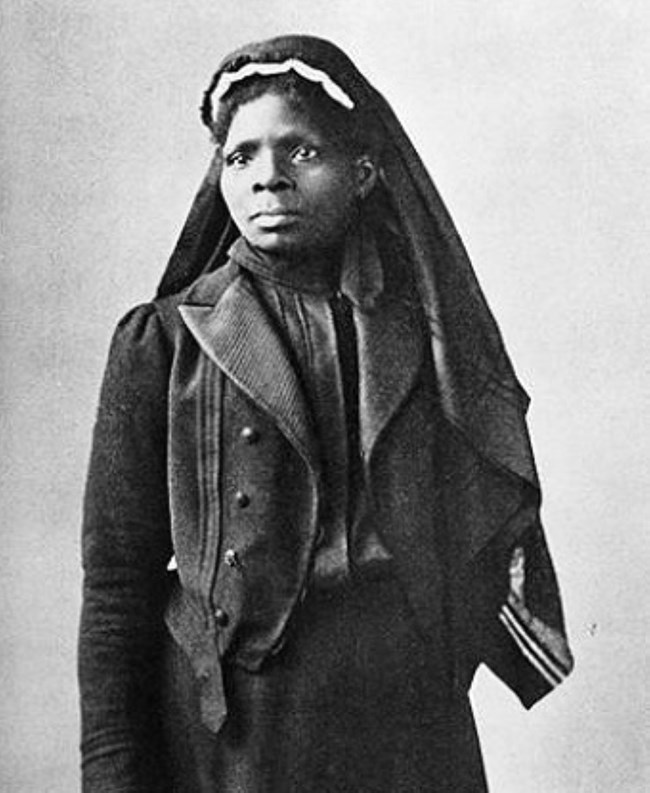

Susie King Taylor

Born into slavery near Savannah, Georgia, on August 6, 1848, Susie King Taylor should never have learned to read and write. Savannah had harsh laws forbidding the formal education of enslaved people. Despite this, she attended two secret schools run by black women, a dangerous act that shaped her entire life.

At only fourteen years old, Taylor took freedom into her own hands and escaped to the waters surrounding Fort Pulaski after it was occupied by the Union. From Fort Pulaski, she made her way north to the South Carolina Sea Islands, where she eventually attached herself to the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, one of the first units to be comprised of formerly enslaved men. Later, they would be redesignated as the 33rd Regiment United States Colored Troops.

Officially employed as a laundress and nurse, Taylor soon filled another role: teacher. At first she taught only the children, but soon she was spending nights teaching adults as well. For the duration of the war, she remained with the 33rd USCT teaching them to read and write, doing laundry, and nursing them when sick or wounded.

In Her Own Words

“Two days after the taking of Fort Pulaski, my uncle took his family of seven and myself to St. Catherine Island. We landed under the protection of the Union fleet, and remained there two weeks...and at last, to my unbounded joy, I saw the “Yankee.” (Reminiscences, page 9)“...in a week or two I received two large boxes of books and testaments from the North. I had about forty children to teach, beside a number of adults who came to me at nights, all of them so eager to learn to read, to read above anything else.” (Reminiscences, page 11)“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn...I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar.” (Reminiscences, page 21)

Reminiscences of My Life in Camp

After the war, Susie King Taylor returned to Savannah, Georgia where she hoped to continue teaching. She opened a private school for newly freed children, but the opening of a public school that same year forced her to close.

In 1872, she moved to Boston, Massachusetts. There she spent the rest of her life devoted to working with the Women’s Relief Corps, an auxiliary to the Grand Army of the Republic for Union women impacted by the Civil War. In 1902, she published a memoir titled Reminiscences of My Life in Camp With the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers.“I now present these reminiscences to you,” she wrote, “hope they may prove of some interest, and show how much service and good we can do each other, and what sacrifices we can make for our liberty and rights...”

In 2018, she was officially inducted as a Georgia Woman of Achievement, which recognizes women who have made significant statewide contributions to Georgia society.At the end of her memoir, Taylor left a final declaration: “Justice we ask,--to be citizens of these United States, where so many of our people have shed their blood with their white comrades, that the stars and stripes should never be polluted.”

Library of Congress

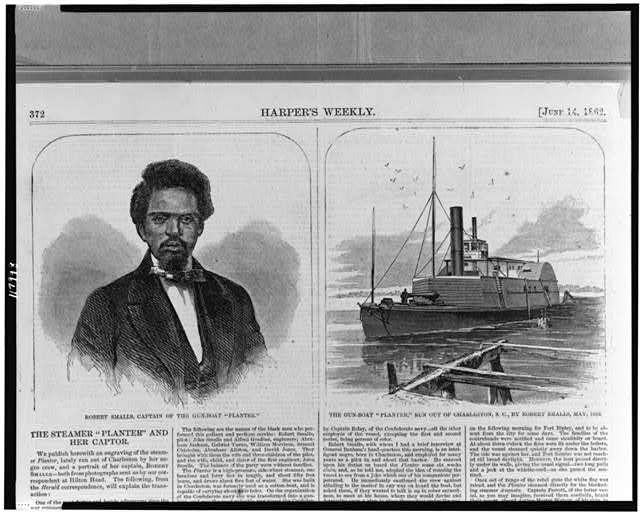

Robert Smalls

Few knew Charleston harbor better than Robert Smalls. Born into slavery on April 5, 1849, Smalls learned early the reality of the life he was a part of. In the fields, he would watch other enslaved people at “the whipping post.” This created a defiance inside of Smalls, a defiance that led him, more often than not, to the local jail.

By the time he was nineteen years old, Smalls had tried out a number of jobs in Charleston, South Carolina. In Charleston, he met and—with their enslaver’s permissions—married his wife, Hannah. They had two children, Elizabeth and Robert Jr., and what should have been a happy family was anything but. The constant fear of one, or all, of their family being sold apart haunted them, as it haunted all enslaved people.In the beginning of the 1860s, he got a job aboard the steamer Planter. It was aboard the Planter that Robert Smalls would take not only his own freedom, but also that of his wife, children, and other enslaved people desperate to be free.

A Courageous Escape

In April or May of 1862, Robert Smalls revealed a dangerous plan to his fellow enslaved workers: he was going to commandeer the Planter and steam it out of Charleston harbor to the Union ships anchored just outside. While it sounds simple, Smalls and his band of freedom seekers had to travel nearly ten miles and pass several heavily armed Confederate fortifications and gun batteries, all without raising an alarm. If caught, the punishment would have been death. With a skeleton crew of nine men along with five women and three children, the escape began in the early hours of the morning of May 13, 1862. They raised two flags, the first official Confederate flag and the South Carolina flag, and Smalls himself wore the captain’s straw-hat. As they passed the Confederate guns, they gave the correct signals required to pass.As they passed beyond the walls of Fort Sumter, they hoisted a white bed sheet and steamed toward the Union blockade. The U.S.S. Onward approached the ship and were greeted by Robert Smalls, who triumphantly shouted out, “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!

A Life of Freedom

Robert Smalls’ story did not end with the Planter. He lobbied for the enlistment of African American soldiers, and when that became a reality he returned to the Planter, this time as a pilot and later captain in the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. He saw seventeen military actions, including the April 7, 1863 assault on Fort Sumter, the same fort he had passed beneath in his escape. When the war ended in April 1865, Robert Smalls was aboard the Planter in Charleston Harbor.

After the war ended, Smalls continued to fight for freedom and equality through politics. He served in the South Carolina state assembly and senate before moving on to serve five nonconsecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives between 1875 and 1887.

In 1895, however, South Carolina passed a revised constitution that stripped African Americans of voting rights. With the rise of Jim Crow laws, Smalls continued to advocate for the political rights of African Americans. “My race,” he stated, “needs no special defense for the past history of them and this country. It proves them to be equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Harriet Tubman

In the early 1820s, a young girl named Araminta was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Like others held in slavery, Minty’s early life was far from easy. As a teenager, she took a severe blow to the head while protecting an enslaved man from an angry overseer. Though she never fully recovered from this blow, her determination to be free only grew stronger.Upon her marriage to John Tubman—a free man—in 1844, Minty changed her name to Harriet Tubman. Five years later, her enslaver died, and Harriet was left wondering what would happen to her. It soon became clear what would happen: she was to be sold away from her family and husband. Resolved not to let this happen, she made up her mind to escape.

At night and on foot, she made her way to Pennsylvania. For the first time, she was free. In Philadelphia, she found work and began to save her money. Even as she created a new life for herself, however, the thought of the loved ones left behind in bondage haunted her. And so, she resolved to change that.

Be Free or Die

Over the ten years prior to the Civil War, Harriet Tubman returned to the south at least thirteen times. With each of these journeys, she brought her family, friends, and other enslaved peoples out of bondage and into freedom. William Lloyd Garrison, a famous abolitionist, called her “Moses” and the nickname stuck.Each time she ventured south; Tubman risked everything. Had she been caught, she would have been severely punished, maybe even killed, and would certainly have been forced back into slavery. And yet she continued to return again and again, bringing more and more freedom seekers out of bondage. For Harriet Tubman, and the people who followed her, the mantra truly was “be free or die.”With Tubman’s help, over seventy people took their freedom.

Freedom at Last

The Civil War did not stop Harriet Tubman in the slightest. Seizing the opportunity, she served the United States army as a nurse, cook, scout, and spy. With the beginning of African American enlistment, Tubman travelled to South Carolina to nurse the new soldiers and civilians.On June 1, 1863, Harriet Tubman joined the 2nd South Carolina Infantry, a unit comprised of newly emancipated men. In a raid along the Combahee River, over 700 enslaved people were rescued from slavery. Many of these newly emancipated people enlisted in the Union army by the end of the war. Tubman’s role in the raid was celebrated in the papers, increasing her fame as a liberator.The conclusion of the war did not dampen Tubman’s passion. With the abolition of slavery, Tubman’s attention turned to women’s suffrage, a cause she served with the same zeal that had led her to risk life and freedom before the Civil War. She passed was in 1913 in her home in New York and was buried with military honors at Fort Hill Cemetery.

Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

The Gullah Geechee

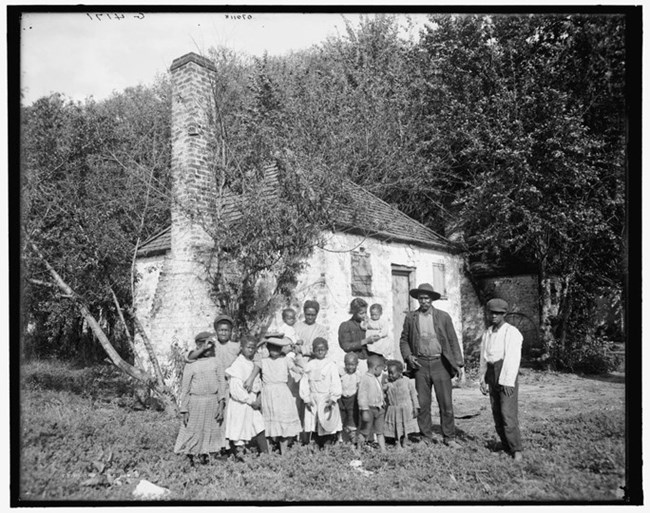

The Gullah Geechee people are descendants of Central and West Africans who were enslaved on the rice, indigo, and Sea Island cotton plantations of lower Atlantic coast. Originally coming from different ethnic and social groups, their enslavement together on the isolated sea islands created a unique culture that preserved many African practices in their language, arts, crafts, and cuisine.

The Gullah language is a unique creole language spoken along the Sea Islands and adjacent coastal areas of South Carolina and Georgia. The residents in Georgia are typically referred to as “Geechee.” The Gullah language began as a simplified form of communication among people of different language including European slave traders, slave owners, and diverse African ethnic groups. Both the vocabulary and the grammatical roots come from a blend of European and African languages. Today, the Gullah Geechee language is the only distinctly African creole language in the United States, and it has influenced traditional Southern vocabulary and speech patterns.

Arts and Food

Though unwillingly taken from Africa and brought to the United States as slaves, the Gullah Geechee people preserved their rick heritage of African cultural traditions in art and music. Much of their arts and crafts came out of the necessity of daily living. Crafts such as making cast nets for fishing, basket weaving for agriculture, and textiles arts for clothing and warmth are still prominent in the Gullah Geechee descendants today.

African cooking methods and seasonings were applied in the Gullah homes and in plantation kitchens, where the cooks were predominantly enslaved women. The traditional diet consisted of locally available foods such as vegetables, fruits, game, seafood, and livestock alongside imported items such as okra, yams, peas, and hot peppers. Rice became a staple crop, and thus a staple food. Despite the bounty of food types, there was not always a bounty of food. As such, making use of available food, making a little go a long way, supplementing with fish, game, and leftovers from butchering and communal stews shared with neighbors were African cultural practices. Today, much of the food referred to as “Southern” comes from the creativity and labor of enslaved Africans on the plantations.

Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

Stretching 12,000 square miles along the coast from Pender County, North Carolina to St. Johns County, Florida, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is not one single site. Instead, it is comprised of many historically and culturally significant places to the Gullah Geechee people. Designated as a National Heritage Area, the purpose of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor is to preserve, share, and interpret the history, traditional cultural practices, heritage sites, and natural resources associated with the Gullah Geechee people of costal North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Educating the public on the history, culture, and traditions of the Gullah Geechee people is an important part of the Heritage Corridor’s mission. They partner with schools, libraries, heritage sites, museums, and community groups to develop and present programs. Along with interpretation, they also welcome opportunities to partner with public and private entities on projects that involve efforts to document, protect, and preserve tangible and intangible Gullah Geechee heritage for the benefit of current and future generations.If you are interested in learning more about the Gullah Geechee people or the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, you can visit their website at gullahgeecheecorridor.org.

Words impact how we relate to the past and to one another.

When sharing the history of Fort Pulaski, we strive to use words that are empathetic to those whose history has been marginalized. For example, we endeavor to use phrases like enslaved rather than slave. Slave is a noun and implies that, at their core, they were nothing more than slaves. The adjective enslaved, on the other hand, implies that though held in bondage, bondage was not their core existence. Furthermore, they were enslaved by the actions of another. Therefore, terms such enslaver rather than master may be heard to emphasize one’s effort to exert power over another. Using these terms along with others reinforces the idea of people’s humanity rather than focusing on the conditions forced upon them. Though they may be simple and small, words have power. Close your eyes and consider the following word groupings.Master vs. Enslaver

Ran away vs. Self-emancipated

Plantation vs. Forced labor camp

Runaway vs. Freedom seeker

Slave vs. Enslaved