Last updated: December 2, 2024

Article

Enslaved to Soldier on the Georgia Coast

NPS

The Fort as Sanctuary

With the US Army encroaching, Confederates abandoned their coastal cotton plantations. A large population of enslaved people was left behind. Freedom seekers began escaping from nearby plantations soon after the US Army conquered Fort Pulaski. The freedom seekers pictured above, some wearing cast-off soldier garb, lived in outbuildings at the fort.

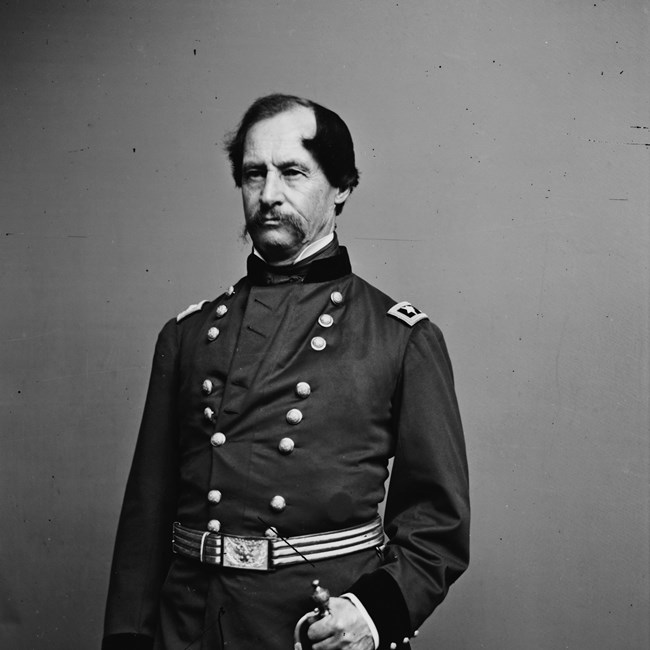

The US army put some of the men to work as laborers around the fort. Freedom seekers also served as navigators through the coastal marshes near Savannah. General David Hunter, commander of the US forces in Georgia and South Carolina, was an ardent abolitionist. He had bigger plans for the newly freed men.

Hunter’s Proclamations

Just two days after the battle for Fort Pulaski, on April 13, 1862, General Hunter issued an emancipation proclamation for all enslaved people on Cockspur Island. A month later, on May 9, 1862, Hunter issued another emancipation proclamation, declaring all enslaved people free in Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida.

President Abraham Lincoln immediately disavowed the May edict. The emancipation of enslaved people, representing millions of dollars of wealth for southerners, was to be handled at the highest levels of government, not by a general commanding troops in the field.

Library of Congress

The Hunter Regiment

Hunter began recruiting African Americans on nearby Hilton Head Island to serve as soldiers. Hunter envisioned an armed force of formerly enslaved men living among the rest of the African American population on the island. To distinguish his force of loyal soldiers, Hunter had the recruits uniformed in bright red trousers.

Hunter’s officers began training the new recruits while Hunter petitioned Washington for gear and weapons for the new soldiers. But the War Department did not support Hunter’s unauthorized experiment.

Lacking War Department support and money, Hunter disbanded the regiment within a few short months. The “volunteers” were sent back to their families without pay, and Hunter requested a new assignment. Yet within a few weeks, he would be vindicated as the War Department raised an official African American regiment off the Georgia coast.

Library of Congress

An Experiment Becomes Reality

In August 1862, the War Department sent General Rufus Saxton, a confirmed abolitionist, to the Georgia coast. He was to oversee the large population of formerly enslaved people now under US control on the coastal islands. Soon after arriving, Saxton got official permission to raise a regiment of African American soldiers. Initially, his recruitment efforts were stymied by the bad experiences in Hunter’s old regiment. The lack of pay for the men was a big stumbling block.

But eventually, the 1st South Carolina Infantry was formed on Hilton Head Island. Thomas Higginson, a Massachusetts abolitionist, was named regimental commander. Colonel Higginson was fond of the men. He encouraged their efforts to learn to read and write in the evening hours when they had finished their military drill. “Their love of the spelling book is perfectly inexhaustible,” Higginson wrote.

Within three months, the regiment was sent on assignments along the coastline, skirmishing with small enemy forces. Higginson was pleased with the results. “They seem peculiarly fitted for offensive operations, and especially for partisan warfare; they have so much dash and such abundant resources, combined with such an Indian-like knowledge of the country and its ways,” Higginson wrote.

The 1st South Carolina continued its forays along the coast throughout the winter of 1863. By spring, the War Department in Washington was satisfied with their progress. The official roll-out of African American regiments began soon thereafter.