Last updated: January 14, 2026

Article

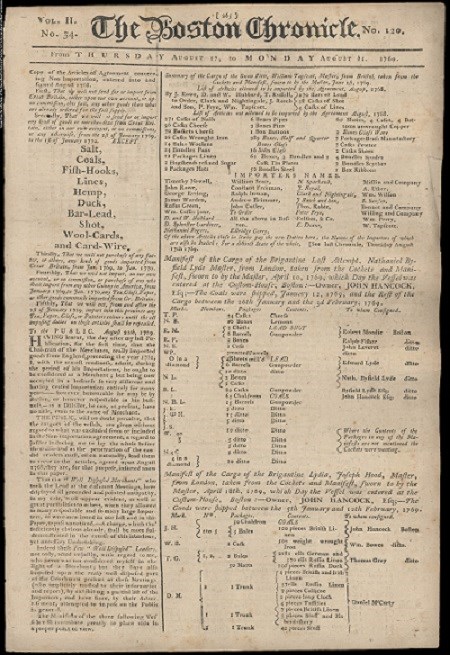

William Molineux: Boston’s Forgotten Firebrand

He had an aversion to all order, civil or Ecclesiastic; he Swore the King was a Tyrant, the Queen a Whore, the prince a Bastard, the Bishops papists, and the House of Lords & Commons a Den of thieves.[1]

On March 15, 1775, Dr. Thomas Bolton, a loyalist, delivered these scathing words at a Boston coffee house. The man Bolton referred to was Boston's William Molineux, who had unexpectedly passed away the previous October. Although five months had passed since Molineux's burial, Boston's loyalists still spoke harshly of the man they argued had played a leading role in igniting rebellion in the colony of Massachusetts.[2]

William Molineux's actions were those of a mob leader, dedicated to using crowd action to achieve liberty. Upon associating himself with the Sons of Liberty, he quickly worked his way up to leadership.[3] Two of his notable contributions as commander of Boston mobs included the upholding of the city’s nonimportation agreements in 1770 and the destruction of tea in 1773.

Massachusetts Historical Society

Following Parliament's passage of numerous acts that taxed goods heavily consumed by colonists, William Molineux became an ardent advocate of nonimportation agreements, or boycotts. Many Boston merchants united in their refusal to import and sell British goods by placing their signatures on the Non-Importation Agreement of 1768.

Molineux commanded enough respect on the streets to lead mobs against anyone who refused to uphold or abide by nonimportation. In 1770, Molineux targeted the two sons of the Massachusetts Royal Governor, Thomas Hutchinson, who had violated nonimportation by secretly stockpiling goods. At a Faneuil Hall gathering, Molineux boldly proposed to lead a crowd to the governor’s home and demand the surrender of the goods. A witness described how Molineux threatened to take his own life when his fellow Sons of Liberty opposed such a radical proposal: "[H]e drew his hands across his Throat, and declar’d he was ready to Die that minute…."[4]

Incensed and frustrated at the passivity of his supposed fellow patriots, Molineux stormed out of Faneuil Hall. Dr. Thomas Young pursued him, crying out to the rest of the Sons of Liberty: "Gentlemen, if Mr. Molineux leaves us, we are forever undone! This day is the last dawn of liberty we ever shall see."[5] William Molineux could only be persuaded to return to the gathering after James Otis and Samuel Adams gave Molineux permission to march on the governor’s residence.[6]

Upon arriving at the governor's residence, Molineux, with the mob behind him, became embroiled in a heated argument with Governor Hutchinson, who shouted down at him from an upper window. The governor ordered the illegal assembly to disperse, for he had no intention of handing his sons over to the Boston rabble.[7]

While Molineux ordered the crowd to depart peacefully that day, his audacious efforts in confronting the royal governor ultimately ended in success. When the Sons of Liberty met at Fanueil Hall the following morning, they learned that Hutchinson, unnerved by Molineux's boldness and fearful of continued unrest in Boston, had instructed his sons to surrender their stockpiled goods.[8]

Library of Congress

Three years later, Molineux yet again controlled the Boston rabble. In 1773, resistance mounted against the Tea Act of 1773, which granted the British East India Company a monopoly over the sale of tea in the colonies. While other cities simply forced the tea ships to return to England, resistance in Boston culminated with the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, in which colonists dumped chests of tea in the harbor.

Two months prior to the Tea Party, Richard Clarke, one of the tea consignees, had received a threatening letter from the Sons of Liberty, which demanded that he appear at the Liberty Tree and publicly resign his commission. When Clarke and the other consignees failed to appear, Molineux led a mob to Clarke's warehouse. Clarke still refused to resign, and Molineux responded that he should "expect to feel…the utmost weight of the people’s resentment."[9] The consignees were forced to take shelter in a locked upstairs room of Clarke’s warehouse and wait for Molineux’s mob to disperse.[10]

Unable to intimidate the tea consignees into resigning, the Sons of Liberty, along with thousands of citizens, gathered at the Old South Meeting House numerous times over the following weeks, beginning with the arrival of the first tea ship in late November. Governor Thomas Hutchinson stood firm, refusing to allow the tea ships to leave Boston without unloading their cargo. At the final meeting on December 16, the gathering became restless as the crowd recognized that the governor would not back down. The Sons of Liberty lost control of the meeting as men began streaming out of the Old South Meeting House.

An eyewitness inside the Old South Meeting House that evening watched the men leaving the building to follow a loud mob that had appeared outside "imitating the Powawas of Indians" as forms of disguise.[11] The unnamed witness recalled that he did not see Molineux, a constant attendee of the recent meetings, at this final meeting, suggesting that Molineux was likely among the mob inciting men to head down to the harbor and dump the tea.[12]

Francis Bernard, the governor who preceded Thomas Hutchinson, declared that William Molineux had been one of the leaders who had proposed that everything possible should be done to prevent the tea from being unloaded from the ships, even if it meant destroying it.[13] After the Boston Tea Party, the British government named Molineux a culpable leader. Governor Hutchinson wrote that Parliament planned to "send over Adams, Molineux, and other principal Incendiaries, try them, and if found guilty, put them to death."[14] If it had not been impractical to send the accused to England for trial, Molineux might have become one of the first great martyrs of the American Revolution.

NPS/Krupinski

William Molineux died suddenly in October 1774. He rests today in Boston's Granary Burying Ground along the Freedom Trail. His headstone, bearing only his name and age at death, remains silent as to his leadership role in the years preceding the outbreak of war in Massachusetts. Buried only feet away from Boston’s most famous Revolutionary leaders, Molineux continues to be overlooked and forgotten as hundreds of thousands of visitors pass by his grave each year, looking to pay their respects to Samuel Adams, John Hancock, or Paul Revere. His memory has been buried underneath the men who survived the American Revolution and went on to become leading figures in the new United States. William Molineux remains Boston's forgotten firebrand.

Footnotes:

[1] Thomas Bolton, An Oration Delivered March 15th 1775 from the Coffee House by Doctor Thomas Bolton, Manuscript Copy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Miscellaneous Bound Manuscripts, Accessed November 2020, http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=3034.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gary Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 97.

[4] John Chester Miller, Sam Adams: Pioneer in Propaganda (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1936), 209.

[5] A.J. Langguth, Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 128.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ray Raphael, Founders: The People Who Brought You a Nation (New York, The New Press, 2009), 81-82.

[8] A.J. Langguth, Patriots: The Men Who Started the American Revolution (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988), 128.

[9] Richard Clarke, “Letter From Messrs. Clarke & Sons, at Boston to Mr. Abrm. Dupuis,” in Tea Leaves: Being a Collection of Letters and Documents Relating to the Shipment of Tea to the American Colonies in the Year 1773, by the East India Tea Company, ed. by Francis Samuel Drake (Boston, MA: A.O. Crane, 1884), 282.

[10] Ibid., 286.

[11] L.F.S Upton, "Proceedings of Ye Body Respecting the Tea," The William and Mary Quarterly 22, no. 2 (April 1965): 298-300.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Volume 11 (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1910), 33.

[14] Thomas Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Esq. ed. Peter Orlando Hutchinson (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co. 1884), 183, Accessed November 2020, http://archive.org/stream/diaryandletters00hutcgoog#page/n12/mode/2up.