Last updated: February 26, 2026

Person

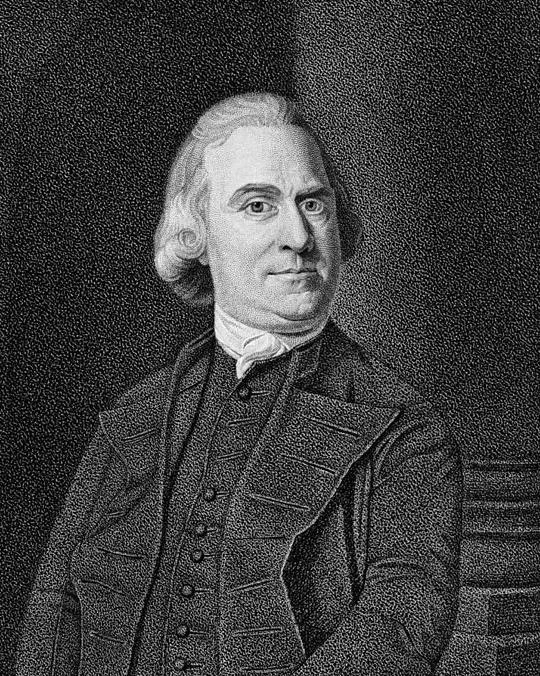

Samuel Adams

Library of Congress

Among the Revolutionary era leaders of Boston, few possessed the fervent passion of Samuel Adams.

Born on September 27, 1722 in Boston to two shipping families, Samuel Adams grew up in a home that encouraged both strict Puritan values and political activism.1 His critical assessment of political systems first arose during his time at Harvard, where Adams published a thesis that argued, "Whether it be lawful to resist the supreme magistrate, if the commonwealth cannot be otherwise preserved?"

Adams' borderline obsession with government and his lack of business acumen prevented him from holding a steady job until his election to the position of tax collector in 1756. His personal life faced its own challenges. His first wife, Elizabeth Checkley, passed away in 1757 after less than ten years of marriage. The tragedy spurred Adams into further pursuing politics. He remarried to Elizabeth Wells in 1764.

When British Parliament passed the Sugar Act in 1764, Adams's role in government changed dramatically. The Act disproportionately affected Massachusetts, leading the Boston Town Meeting to task Samuel Adams with verbalizing their opposition. Adams took to the task with enthusiasm, writing, "If Taxes are laid upon us in any shape without our having a legal Representation where they are laid, are we not reduced from the Character of free Subjects to the miserable State of tributary Slaves?"2

Parliament continued to pass taxes and duties despite Adams’s fiery protestations. When the Stamp Act passed in 1765, Samuel Adams was elected to represent Boston in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He arranged boycotts and petitions in opposition to the Townshend Acts. And all throughout, Adams published articles under the pseudonyms 'Vindex' and 'Candidus.' The stirring of public opinion led to British troops being sent to occupy Boston. The military's presence, and its clashes with the Bostonians, eventually led to the Boston Massacre.

The massacre played right into Adams's hands. With blood in the streets, Adams and the Town Meeting demanded Massachusetts governor Thomas Hutchinson withdraw the troops from Boston and arrest the soldiers involved in the Massacre. Samuel Adams's own cousin, John Adams, defended the troops during their trial, winning the majority of them 'not guilty' verdicts.

After British troops withdrew to Castle William, an uneasiness settled in Boston until the passage of the 1773 Tea Act. Failing to come to a resolution with the royal government regarding the highly taxed imported tea, colonists took direct action. On December 16, 1773, colonists stormed from Old South Meeting House to Griffin's Wharf and destroyed over 300 chests of tea. Adams praised this act of resistance, writing, "You cannot imagine the height of joy that sparkles in the eyes and animates the countenances as well as the hearts of all we meet on this occasion."3

Parliament's response to this event came in 1774 with the Coercive Acts, later known as the Intolerable Acts. The Acts closed the port of Boston, stripped Massachusetts of its charter, limited town meetings to one a year, and stationed troops within Boston itself. The First Continental Congress formed in response to this alarming escalation, with Samuel Adams representing Massachusetts as one of its delegates. Adams quickly found that the representatives of other colonies did not entirely trust Massachusetts. Some even feared that Massachusetts would declare independence, defeat Britain, and then invade the other colonies. Assuaging these fears and rallying the assistance of the other colonies to protesting the Intolerable Acts became Adams's primary concern.4

While in Philadelphia, Samuel Adams encouraged his fellow revolutionary, Joseph Warren, to create an opposition government in Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. When Adams returned to Massachusetts, he joined the Provincial Congress in Concord, staying in Lexington with John Hancock. When British troops marched on Concord to destroy stored weapons, Adams and Hancock met with the militia gathering at Lexington Green. Their encouragement helped to spark the resulting Battle of Lexington and Concord.

Fleeing to Philadelphia, Adams and Hancock joined the Second Continental Congress. With fighting underway, Adams came out strongly in favor of independence rather than reconciliation. Like many of the other delegates, Adams signed the Declaration of Independence.5

As war continued, Samuel Adams returned to Massachusetts in 1779 to help draft Massachusetts' new constitution before retiring from the Continental Congress in 1781. He remained active in politics after the Revolution, becoming Lieutenant Governor under John Hancock from 1789 to 1793. After Hancock's death, Adams won the governorship for himself, serving from 1793 to his retirement in 1797. Adams passed away on October 2, 1803 in Boston.

Learn More...

Samuel Adams: Boston's Radical Revolutionary

Footnotes:

- Samuel Adams's birth date is at times listed as September 16, 1722, for Old Style. “Samuel Adams | Biography, History, Accomplishments, Boston Tea Party, & Facts,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed October 6, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Samuel-Adams.

- Samuel Adams, "Samuel Adams to the Representatives of Boston, May 24, 1764," in The Writings of Samuel Adams vol I 1764-1769, edited by Harry Alonzo Cushing (G.P. Putnum, 1904) 5.

- Samuel Adams to Arthur Lee December 31, 1773, accessed November 2021, Samuel Adams Heritage Society.

- Nathaniel Philbrick, Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, and a Revolution (New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2013) 74.

- Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life, (The Penguin Press, 2010), 186.