Last updated: January 12, 2023

Article

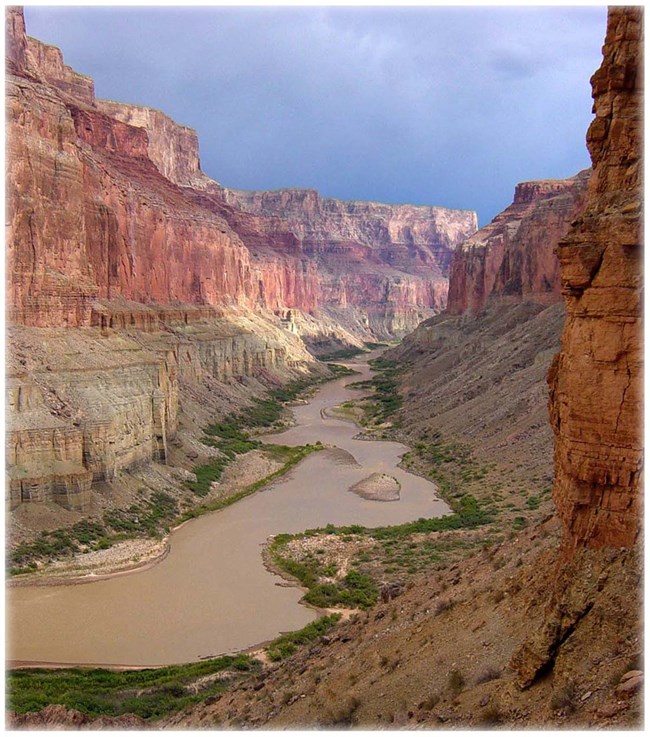

Water Resources on the Colorado Plateau

NPS/M.QUINN

From the magnificent cliffs of the Grand Canyon to the graceful arches of Southeast Utah, the Colorado Plateau has been shaped by water. This arid to semiarid region has been home to diverse wildlife, vegetation, and people for thousands of years. The contrast of delicate life among the formidable landscape fascinates visitors from all over the globe. In recent years, however, the area has experienced extreme drought, rising temperatures, and other threats that are expected to persist. How will this affect water—and therefore life—on the Colorado Plateau? Will lifeless trees pervade the landscape and native grasses wither away? Will species disappear? What would this mean for future generations of residents and visitors?

To better understand how water impacts life on the Colorado Plateau, we examine where the water came from, who uses it and for what purposes, what threatens water quality and quantity, and finally, how we can protect and conserve this precious resource.

Sources of Water

Scientists think Earth’s water originally came from water-laden comets or asteroids that crashed into our planet. Others suggest that Earth’s own rock could have contained enough hydrogen to release water during early volcanic activity. But since its appearance at least 3.8 billion years ago, water on Earth has moved in a continuous, familiar cycle. It falls as precipitation, flows over the land, and collects in depressions. Some water seeps into the ground, some evaporates, and the cycle continues. For millions of years, this movement of water has altered the surface of the earth. Ancient seas rose and receded, and rivers carved canyons in rock. On the Colorado Plateau, we see evidence of water’s enduring influence in fossils and in landforms like the Grand Canyon. Long before the canyon existed, water helped to form the sedimentary rock that now comprises the canyon walls, preserving delicate remnants of an early marine environment in the process. Today the Colorado River continues its work in the canyon, scouring the jagged narrows and laying sandbars along its path. While water continues to physically shape the Colorado Plateau, access to this water has an equally powerful effect on life there. Wildlife, vegetation, and humans on the Colorado Plateau rely on three sources of water: precipitation, surface water, and groundwater.

Precipitation

As in most other regions, precipitation is a fundamental source of water on the Colorado Plateau. The amount and timing of precipitation strongly influences ecosystems. For example, in the southern portion of the Colorado Plateau ecosystems depend on a bimodal precipitation regime—a cycle of winter snows and summer monsoons. These precipitation patterns affect soil moisture and vegetative growth, erosion, and the persistence of habitats, especially riparian habitats. Perhaps most significantly, precipitation affects the amount and availability of surface water and groundwater.

Surface Water

As precipitation falls to the earth, it is captured and channeled within distinct land areas called watersheds. The Colorado Plateau is part of the Colorado River watershed. Here, water collects primarily in higher elevations and drains into streams and rivers that ultimately flow toward the Colorado River. Some water collects to form lakes, ponds, or wetland areas. Other sources of surface water are seasonal or temporary, such as ephemeral streams or tinajas (temporary pools). All surface water sources in this dryland region, even temporary ones, are crucial for the ecosystems they serve. Springs are especially important sources of surface water on the Colorado Plateau. A spring occurs where groundwater naturally flows out of the ground, saturates the soil, or collects in a pool. Spring flow is determined by groundwater levels. In arid areas, springs are a lifeline for wildlife and vegetation. Ancient peoples including the Ancestral Puebloans and the Sinagua, and later the Hopi, Navajo, Zuni, and other Native American Indian Tribes relied on the accessible water that springs provided.

NPS

Groundwater

As surface water flows over the land, some of it sinks deep into the ground and becomes groundwater. Groundwater is stored in aquifers, units of water-bearing rock or sediment. The principal aquifers in the Colorado Plateau region are sandstone aquifers. In sandstone aquifers, groundwater moves along bedding planes, through cracks, and within pore spaces in the rock. While water does not flow as easily through sandstone as it can through unconsolidated gravel or sand, sandstone aquifers can still yield large amounts of groundwater. Older, deeper groundwater generally contains more salts and minerals than groundwater that is closer to the land surface. Within the Colorado Plateau, much of this deeper groundwater is saline and not suitable to drink or use for agriculture without significant treatment. It can take decades, centuries, or even millennia for water to reach or recharge an aquifer. But groundwater can be withdrawn from aquifers much more quickly through wells. When groundwater leaves an aquifer faster than the aquifer can recharge, the groundwater level declines; this can reduce the amount of water available for springs and streams.

SIMON WELLS

Uses of Water

All life on the Colorado Plateau depends on water. Even small patches of water-saturated soil provide vital nourishment for ecosystems. Grasses, shrubs, trees, and other vegetation provide food and shelter for wildlife. Insects and other invertebrates pollinate plants and are a source of food for birds and other animals. For thousands of years, humans have used this water to survive on the Colorado Plateau. Ancient peoples filled their vessels with water from streams and springs; they diverted water from rivers to irrigate their crops.

Today, under the pressure of an ever-growing population, humans pump millions of gallons of groundwater daily. According to a USGS report, an estimated 365 million gallons of groundwater per day were withdrawn from Colorado Plateau aquifers in 2015. That’s more water than 20 inches of rain over a square mile per day. Most of this groundwater is used for growing food, for drinking and other household uses, for generating energy, and for producing or extracting materials for the products we use today.

Surface water has also been harnessed to provide water and generate energy for the growing population. An example of this is the Glen Canyon Dam within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. This dam on the Colorado River created Lake Powell, and it helps to meet the energy and water needs of millions of people.

GARY LADD

Recreation is another important use of surface water on the Colorado Plateau. Water activities such as fishing, swimming, river rafting, boating, and kayaking provide opportunities for people to relax and enjoy nature. These opportunities are an important benefit of our national parks.

Threats to Water

While water is essential for human survival, most threats to water quality, quantity, and availability are caused by humans. To address these threats, we must first recognize and understand them.

Climate Change

Climate change is a significant threat to water on the Colorado Plateau. Climate trends suggest that if we do nothing to address climate change, rising temperatures, increased evaporation, and changing precipitation patterns will adversely affect water availability. Historic drought is already affecting the region; on August 16, 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation declared the first ever water shortage in the Colorado River Basin system, reducing water availability in the region. Not only will surface water continue to decrease, but groundwater levels may also decline due to insufficient recharge as well as possible increased pumping. As a result, water may cease to flow from some springs, and the water in streams and lakes may decrease. This will lead to cascading consequences for the Colorado Plateau, including decreased vegetative cover, increased erosion, and species loss.

Increased Population and Development

The influx of people to the Four Corner states has been increasing steadily and shows no sign of slowing. From 2010 to 2020, the combined population of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico increased by more than two million people.Today about 40 million people use water from the Colorado River. But as the population continues to increase, demand for water will also increase. This increased demand, compounded by climate change, may exceed supply in the near future, heightening the risk of continued water shortages.

Where there is not enough surface water to support human populations, humans withdraw groundwater through wells. But excessive withdrawal leads to groundwater decline and depletion. This has several possible negative effects:

-

Loss of water below ground can cause the ground above to collapse, known as land subsidence.

-

Water in springs and streams is reduced.

-

Deeper wells and/or increased pumping will be required to access declining groundwater levels.

-

As groundwater declines, deep saline water is drawn upward, contaminating the groundwater with high amounts of salts and minerals.

MOR, CC LICENSE

Contaminants

Contaminants, from plastics to pesticides to pharmaceuticals, often enter water. Some contaminants occur naturally such as metals from dissolved rock. Other contaminants are introduced by humans and can enter water in many ways:

-

agricultural runoff

-

chemical spills

-

wastewater effluent

-

litter

-

sunscreen from swimmers

Contaminants can harm vegetation, wildlife, and humans, and some can have long-lasting effects. For example, abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation have been a prolonged source of water contamination, resulting in over a decade of remediation and monitoring. An ongoing study has shown that residents in the area have higher than normal levels of uranium in their bodies, which can lead to numerous health issues for humans and animals alike.

While radioactive and other toxic substances are an obvious threat, even relatively harmless substances can be harmful at high concentrations. Nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus—abundant in fertilizers and wastewater—can cause overgrowth of algae and other aquatic plants. This unsightly overgrowth blocks light and reduces oxygen in the water, which can kill fish and other organisms.

MOAB ADVENTURER CC LICENSE

How Can We Protect Our Water?

Are we doing all we can to protect our water? This indispensable resource sustains life, provides power and recreation, and brings beauty to our lives, yet our actions can threaten the quality, quantity, and availability of water. With human ingenuity and perseverence, we can address threats and preserve our natural resources. Below are some examples of what we can do as citizens and leaders in the region to safeguard our water supply.

Conserve Water

-

Choose drought-tolerant vegetation for landscaping.

-

Prevent evaporation: water landscaping when it Is cooler outside.

-

Plant crops that require less water.

-

Reevaluate water sources: rather than pumping more groundwater, consider using harvested rainwater or recycled gray water.

-

Use reclaimed water where possible and appropriate, such as for toilet flushes, irrigation, and aquifer recharge.

-

Fix leaky pipes.

-

Install water-efficient fixtures.

-

Turn off the tap.

Protect Water Quality

-

Properly dispose of waste, including plastics, electronics, batteries, oil, and medications.

-

Pick up pet waste, especially near water sources.

-

Use mineral-based sunscreen.

-

Reduce fertilizer and pesticide use.

-

Evaluate wastewater treatment: Improved technology can significantly reduce contaminants in effluent.

Encourage Others to Protect Water

-

Help family and friends take action to protect water.

-

Learn more about regulations that protect water, like the Clean Water Act.

-

Participate in government: vote, attend public meetings, and contact legislators.

Protecting water can’t wait. We must act today to preserve this precious resource and ensure that life on the Colorado Plateau will continue to flourish for generations to come.

This article was prepared by SCPN Volunteer Intern Crystal Faucett, with Jean Palumbo.

Resources

Lovelace, J.K., Nielsen, M.G., Read, A.L., Murphy, C.J., and Maupin, M.A., 2020, Estimated groundwater withdrawals from principal aquifers in the United States, 2015 (ver. 1.2, October 2020): U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1464, 70 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1464.

National Climate Assessment. 2017. Fourth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 3: Water.

National Climate Assessment. 2017. Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States.

National Integrated Drought Information System. 2021. Drought Update for the Intermountain West.

National Park Service. Nd. Conserving Water.

National Public Radio. 2020. Water, Water, Every Where — And Now Scientists Know Where It Came From.

Nature. Nd. Living Volcanoes: Volcanic Theory of Water.

New York Times. August 16, 2021. In a First, U.S. Declares Shortage on Colorado River, Forcing Water Cuts.

NOAA. 2021. Why do we have an ocean?

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. 2012. Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study Executive Summary.

U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. August 16, 2021. News Release: Reclamation announces 2022 operating conditions for Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2021. Historical Apportionment Data Map.

U.S. Geological Survey. 2000. Ground Water Atlas of the United States: Segment 2, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah.

U.S. Geological Survey. 2021. Sandstone aquifers.

Tags

- arches national park

- aztec ruins national monument

- bandelier national monument

- bryce canyon national park

- canyon de chelly national monument

- canyonlands national park

- capitol reef national park

- chaco culture national historical park

- el malpais national monument

- el morro national monument

- glen canyon national recreation area

- grand canyon national park

- hovenweep national monument

- hubbell trading post national historic site

- mesa verde national park

- natural bridges national monument

- navajo national monument

- petrified forest national park

- petroglyph national monument

- rainbow bridge national monument

- salinas pueblo missions national monument

- sunset crater volcano national monument

- walnut canyon national monument

- wupatki national monument

- yucca house national monument

- southern colorado plateau network

- scpn

- sw science

- research

- project

- climate change

- water conservation

- water in the west

- water resources

- groundwater

- jmrlc

- natural resources

- water