Last updated: March 3, 2021

Article

Vado, New Mexico on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail

Photo/Historical Society of Southeast New Mexico

In the Mesilla Valley, approximately 15 miles south of Las Cruces, New Mexico, along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro National Historic Trail, lies the community of Vado. The rich history of the small town was shaped by the efforts of Francis Marion Boyer and Ella Louise McGruder Boyer, who arrived in New Mexico from Georgia in the early 1900s and founded the first all-African American settlement in the territory.

After being threatened by members of the Ku Klux Klan, Boyer’s father who had served in the southwest with the US Army during the Mexican-American War, encouraged his son to move west. There the Boyers could realize their dream of a community where individuals could raise families and own land away from the racial violence and discrimination of Jim Crows laws in the post-Civil War southeast.

While the dates vary by source, around 1899, Boyer began the long trek with two other young men from Georgia to the Lower Pecos Valley outside of Roswell, New Mexico. Boyer was followed a few years later by his wife and children. The settlers printed newspaper advertisements encouraging others to join them, and in 1903 the Boyers and twelve other African American homesteaders established the Blackdom Townsite Company. The articles of incorporation prioritized the economic and intellectual development of the community, including a system of education.

The residents of Blackdom laid out 166 homesites in addition to a post office, general store, public square, church, several businesses, and a one-room community school serving eight grades. The community practiced self-governance and residents pursued livelihoods as farmers, ranchers, business entrepreneurs, and as oilmen. Here Boyer established several organizations including the first masonic lodge in the county.

At its peak, more than 300 individuals called Blackdom home. Success of the community was dependent upon a favorable climate and access to sufficient water for farming. Above average rainfall during the early 1910s helped the settlers prosper, but drought and crop failure in following years led to the community’s decline.

In 1920, after years of ongoing drought, the Boyers led six wagonloads from Blackdom southwest to the Rio Grande Valley to establish a new community in Vado, New Mexico. From the 1920s through 1930s, the Boyers welcomed between 40 and 60 Black families to the community. A town council was established to govern, and families dug drainage ditches to harness the water of the Rio Grande for farming. While it took substantial work to sustain the desert community, there was also time for merriment. Vado experienced its heyday from the late 1930s through 1950s and during this time an annual Juneteenth celebration was attended by individuals from across southern New Mexico and beyond.

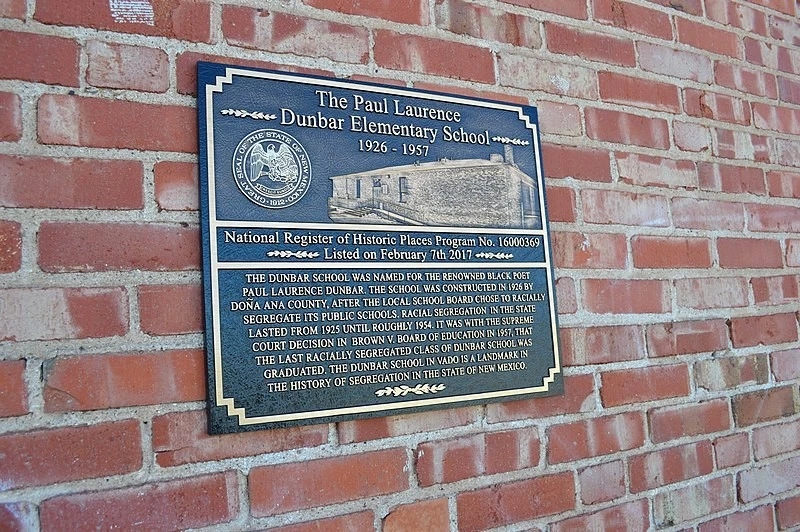

The Boyers remained committed to their original vision of education as a central pillar in community life and in 1923 built a one-room adobe schoolhouse to serve Vado’s African American youth. State law upheld racial segregation in schools and in 1926, a second facility, the Paul Lawrence Dunbar School, opened in Vado. The brick schoolhouse had four large rooms and served 175 children and operated until 1957, when the Gadsden School District was integrated. The school, named for the internationally acclaimed 19th-century Black poet, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2017.

New Mexico State Historic Preservation Officer Jeff Pappas stated, “The Dunbar school is a landmark in the history of segregation and in the history of African Americans in New Mexico.” The Dunbar School is among six surviving schools built during segregation in New Mexico.

In the 1950s many families began to move away from Vado for other opportunities. While the population declined, Francis and Ella Boyer continued to contribute to the community through a range of social and educational programs in Vado until their deaths in 1949 and 1965, respectively. The Boyers are buried in the Vado Riverview Cemetery in the small community that they called home for several decades, though their influence extends far beyond.

Photo/WikiMedia Commons

Photo/Artesia Historical Museum and Art Center

- Binkovitz, Leah. “Welcome to Blackdom: The Ghost Town That Was New Mexico’s First Black Settlement.” Smithsonian Magazine. February 04, 2013. <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/welcome-to-blackdom-the-ghost-town-that-was-new-mexicos-first-black-settlement-10750177/>

- “Blackdom New Mexico.” Homestead National Historical Park. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Accessed February 15, 2021. <https://www.nps.gov/places/blackdom-new-mexico.htm>

- “Blackdom, New Mexico.” New Mexico History: A blog about New Mexico. March 20, 2018. <https://newmexicohistoryblog.wordpress.com/2018/03/20/blackdom/>

- “Blackdom: The First All-Black Settlement in New Mexico – A Story Map.” University of New Mexico, Resource Geographic Information System. March 9, 2015. <https://rgis.unm.edu/blackdom/>

- “Blacks in a Border Country.” Frontera NorteSur: Online News Coverage of the US-Mexico Border, New Mexico State University. September 22, 2001. <https://fnsnews.nmsu.edu/blacks-in-a-border-county>

- “Francis Marion Boyer.” Homestead National Historical Park. US Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Accessed February 15, 2021. <https://www.nps.gov/people/francis-boyer.htm>

- “Vado’s Founder Walked from Georgia.” El Paso Times, February 13, 2010. <https://elpasotimes.typepad.com/morgue/2013/06/vados-founder-walked-from-georgia.html>

- “Vado, New Mexico.” Henry Boyer Family Reunion Group, Inc. Accessed February 16, 20201. <http://boyerhenryreunion.com/vado-history-part-1.html>

- “Vado School, a ‘Landmark in History of African American ins N.M.,’ Listed in National Register.” Artesia Daily Press, February 28, 2017. <http://www.artesianews.com/1428901/vado-school-a-landmark-in-history-of-african-americans-in-n-m-listed-in-national-register.html>

- Walton, M.A. “Vado, New Mexico: A Dream in the Desert.” Southern New Mexico Historical Review, Dona Ana County Historical Society, Volume II, No.1., Las Cruces, New Mexico (January 1995). <http://www.donaanacountyhistsoc.org/HistoricalReview/1995/HistoricalReview1995.pdf>

- Wiseman, Regge N. “Glimpses of Late Frontier Life in New Mexico’s Southern Pecos Valley: Archaeology and History at Blackdom and Seven Rivers.” Museum of New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies. Archaeology Notes 233 (2001). <http://www.nmarchaeology.org/assets/files/archnotes/233.pdf>

- Blackdom School, with Blackdom school teacher Loney K. Wagoner on far right with children in his class (photo: Historical Society of Southeast New Mexico)

- A sketch of Blackdom's town plan including street and property names (Source: Historic Preservation Division, Office of Cultural Affairs, Santa Fe)

- Francis Boyer, Blackdom's founder, sits centered among his family and some of Blackdom's earliest residents (Source: Artesia Historical Museum and Art Center)