Last updated: March 19, 2025

Article

Climate and Water Monitoring at Tumacácori National Historical Park: Water Year 2022

NPS

Overview

Together, climate and hydrology shape ecosystems and the services they provide, particularly in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Understanding changes in climate, groundwater, and surface water is key to assessing the condition of park natural resources—and often, cultural resources.

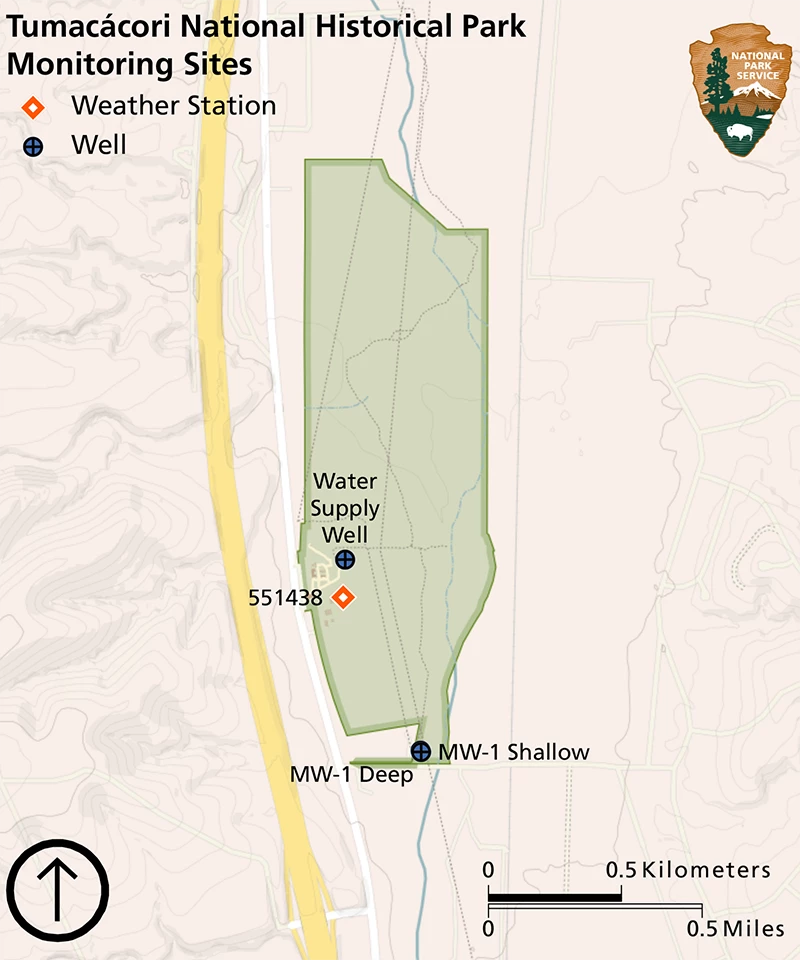

At Tumacácori National Historical Park (Figure 1), Sonoran Desert Network scientists study how ecosystems may be changing by taking measurements of key resources, or “vital signs,” year after year—much as a doctor keeps track of a patient’s vital signs. This long-term ecological monitoring provides early warning of potential problems, allowing managers to mitigate them before they become worse. At Tumacácori National Historical Park, we monitor climate and groundwater, among other vital signs.

Groundwater conditions are closely related to climate conditions. Because they are better understood together, we report on climate in conjunction with water resources. Reporting is by water year (WY), which begins in October of the previous calendar year and goes through September of the water year (e.g., WY2022 runs from October 2021 through September 2022).

This article reports the results of climate and groundwater monitoring at Tumacácori National Historical Park (Figure 1) in WY2022.

NPS

Climate and Weather

There is often confusion over the terms “weather” and “climate.” In short, weather describes instantaneous meteorological conditions (e.g., it’s currently raining or snowing, it’s a hot or frigid day). Climate reflects patterns of weather at a given place over longer periods of time (seasons to years). Climate is the primary driver of ecological processes on earth. Climate and weather information provide context for understanding the status or condition of other park resources.

A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Cooperative Observer Program (COOP) weather station (ID# 028865) has been operational at Tumacácori National Historical Park since 1946 (Figure 1). This station typically provides a reliable climate dataset. However, in WY2022 the station was missing data on 90 days. As a substitute, climate analyses in this year’s report use 30-year averages (1991–2020) and gridded surface meteorological (GRIDMET) data from the location of the Visitor Center at Tumacácori National Historical Park. Subsequent reports may revert to the weather station as the data source, depending on future data quality.

GRIDMET is a spatial climate dataset at a 4-kilometer resolution that is interpolated using weather-station data, topography, and other observational and modeled land-surface data. Temperature and precipitation estimated from GRIDMET may vary from actual weather at a particular location, depending on the availability of weather station data and the difference in elevation between the location of interest and that assigned to a grid cell. Data from both the weather stations and GRIDMET are accessible through Climate Analyzer.

Results for Water Year 2022

Precipitation

Annual precipitation at Tumacácori National Historical Park in WY2022 was 17.15″ (43.6 cm; Figure 2), 1.52″ (3.8 cm) more than the 1991–2020 annual average. This surplus occurred in June, August, and September, which had rainfall totals above the 1991–2020 monthly averages. June had over four times the average rain amount. Rainfall amounts in all other months were less than the 1991–2020 averages, with three months receiving no measurable rain (Figure 2).

Air Temperature

The mean annual maximum air temperature at Tumacácori National Historical Park in WY2022 was 81.6°F (27.6°C), 1.1°F (0.6°C) above the 1991–2020 average. The mean annual minimum temperature in WY2022 was 47.6°F (8.7°C), only 0.1°F (0.1°C) warmer than the 1991–2020 average. Mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures in WY2022 differed by as much as 5.9°F (3.3°C; see November as an example) relative to the 1991–2020 monthly averages (Figure 2). Mean monthly maximum temperatures were warmer than the 1991–2020 monthly averages in all but three months. Mean minimum monthly temperatures were more variable relative to the 1991–2020 averages.

NPS

Drought

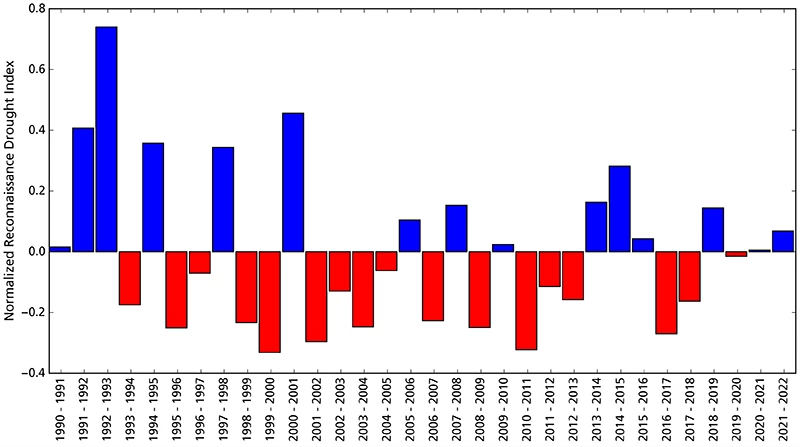

Reconnaissance drought index (Tsakiris and Vangelis 2005) provides a measure of drought severity and extent relative to the long-term climate. It is based on the ratio of average precipitation to average potential evapotranspiration (the amount of water loss that would occur from evaporation and plant transpiration if the water supply was unlimited) over short periods of time (seasons to years). The reconnaissance drought index for Tumacácori National Historical Park indicates that WY2022 was slightly wetter than the 1991–2022 average from the perspective of both precipitation and potential evapotranspiration (Figure 3).

Reference: Tsakiris G., and H. Vangelis. 2005. Establishing a drought index incorporating evapotranspiration. European Water 9: 3–11.

NPS

Groundwater

Groundwater is one of the most critical natural resources of the American Southwest, providing drinking water, irrigating crops, and sustaining rivers, streams, and springs throughout the region.

Methods

Tumacácori National Historical Park groundwater is monitored at three wells by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (Figure 1). The Water Supply Well is manually monitored quarterly. The co-located MW-1 Deep and MW-1 Shallow wells are monitored using automated methods. Data are available at the Arizona Department of Water Resources Well Registry Search.

Recent Findings

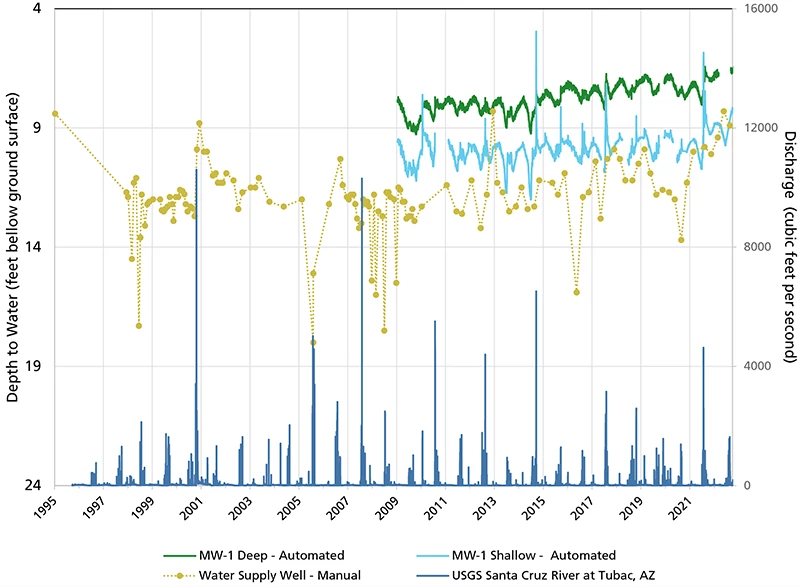

Groundwater monitoring results for WY2022 are summarized in Table 1. Mean depth to water at all wells was slightly higher than in WY2021. Water levels in all three wells appear to be trending slightly upward (Figure 4). This increase has a few likely drivers, including above-average rainfall in recent years and increasing discharge of treated effluent from the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant. Further studies and additional monitoring are needed to determine if this trend continues and, if it continues, to attribute the primary sources of the recharge. The MW-1 Shallow well represents the shallow aquifer, and therefore has greater seasonal fluctuations over the monitoring record due to the influence of seasonal precipitation, high flow events, and evapotranspiration in the riparian area. The MW-1 Deep well represents the deeper confined aquifer, which is buffered from large rain and streamflow events, resulting in fewer fluctuations relative to the shallow aquifer. The water level in MW-1 Deep is usually higher than in MW-1 Shallow due to elevated pressure in the confined aquifer. The Water Supply Well is also completed in the deep aquifer, but has experienced greater fluctuations, likely because this well is routinely pumped to support the park’s water needs and is also located farther from the Santa Cruz River than the other monitoring wells.

| Name | State Well Number | Wellhead Elevation (est. ft amsl) |

Average Depth to Water (ft bgs) |

Average Water Level Elevation (ft amsl) |

Change in Elevation from WY2021 (± ft) |

Change from Earliest Recorded Water Level (± ft) (year of record) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Supply Well | 629110 | 3,250.00 | 9.18 | 3,240.82 | 1.19 | 2.53 (1960) |

| MW-1 Deep | 551438 | 3,262.60 | 6.82 | 3,255.78 | 0.55 | 1.06 (2009) |

| MW-1 Shallow | 551439 | 3262.76 | 9.03 | 3,253.73 | 0.60 | 0.56 (2009) |

NPS

Report Citation

Authors: Kara Raymond, Andy Hubbard, Cheryl McIntyre

Raymond, K., A. Hubbard, and C. McIntyre. 2024. Climate and Water Monitoring at Tumacácori National Historical Park: Water Year 2022. Sonoran Desert Network, National Park Service, Tucson, Arizona.