Last updated: September 19, 2022

Article

Tipping the Scales

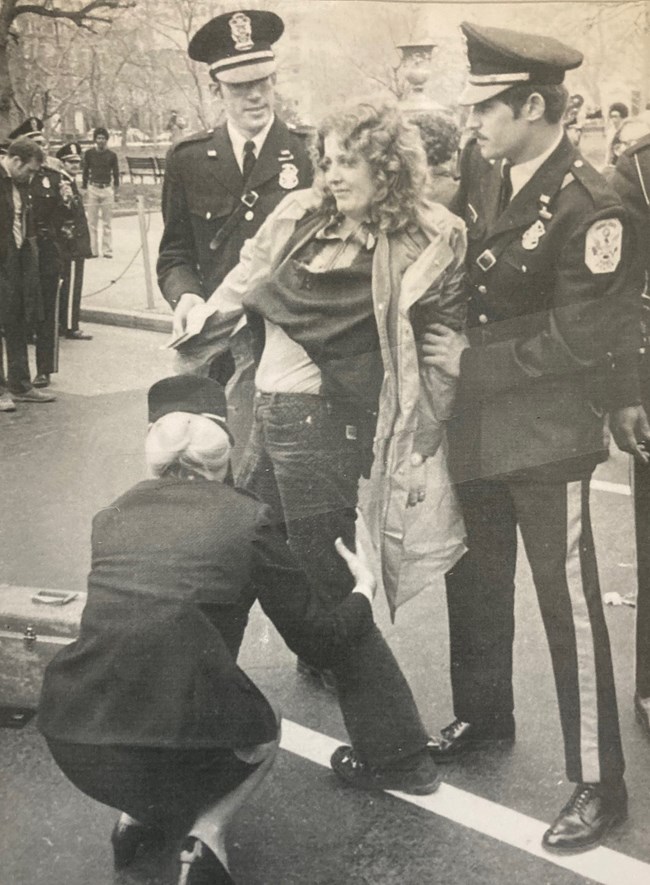

The 1970s saw the expansion of US Park Police (USPP) units, responsibilities, and force size. Equal employment opportunities resulted in more women and minority officers joining the rapidly evolving organization. Although policewomen were still a small percentage of the force, their numbers began to increase in the mid-1970s. They weren’t always accepted by their fellow officers, however, and many faced discrimination and hostile work environments.

Law and Order

Civil rights demonstrators, anti-war protesters, and counterculture youths presented law enforcement challenges to USPP officers in Washington, DC, throughout the 1960s and early 1970s. In addition, as visitation in national parks increased, crime rates did too. Park rangers often found themselves ill-equipped to deal with these issues spreading from urban areas into western parks such as Yosemite, Grand Canyon, and Yellowstone. This lack of preparedness is perhaps best illustrated by the Stoneman Meadow riots at Yosemite, a violent clash between “hippies” and rangers and other National Park Service (NPS employees) during the Independence Day holiday weekend in 1970.

Following the riots, some argued that the emphasis of NPS law enforcement shifted from protecting park resources to policing people’s behaviors. Congress’s concern for law and order in national parks was reflected in a $550,000 budget increase for 1971 to help the USPP combat the unrest. In addition, a USPP law enforcement specialist was assigned to each NPS region and a “strike force” of USPP officers was created to respond to trouble anywhere in the NPS on 12 hours’ notice.

In 1972, training for all federal law enforcement personnel (except FBI agents and military police) was consolidated to a 12-week basic training program at the Treasury Department’s Consolidated Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (CFLETC) in Washington, DC. Graduates of CFLETC then took five weeks of specialized training in local laws and park regulations followed by nine weeks under a field training officer for on-the-job training.

By 1973 the NPS had accumulated a small arsenal of police equipment. A new USPP Aviation Unit was established to provide aerial observations, photography, and rescue services. A year later 70 percent of the vehicles the NPS requested from Congress were police patrol cars.

In February 1974 the USPP also dramatically expanded its areas of operation, creating the San Francisco and New York field offices to provide visitor services, protection, and security at Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Gateway National Recreation Area, respectively. These new areas, together with ongoing social unrest, created both policing challenges and new job opportunities. A June 18, 1974, article in the New York Daily News noted that USPP “applicants, men and women, must be American citizens, 21 to 29, with two years of college.”

Gaining Ground

The November 1972 judgment changing Measuring Up standards for women, together with aggressive affirmative action recruitment and changing conditions within the USPP organization, saw more than twice as many policewomen hired in 1974 than in the previous 30 years combined. At least 15 women joined the force, including:

- Annie Simons (February 2, 1974)

- Carolyn Mercer (February 3, 1974)

- Grace Goodier (February 16, 1974)

- Kathleen “Casey” Carlson (February 17, 1974)

- Gwendolyn Winston (February 17, 1974)

- Donna Roberts (March 3, 1974)

- Sandra L. Clark (March 17, 1974)

- Diana Smith (April 28, 1974)

- Linda Gray (April 28, 1974)

- Betty Griffin (Summer 1974)

- Karen Lee (Summer 1974)

- Marcia Cronan (Summer1974)

- Susan Howell (Summer 1974)

- Marilee Morgan (Summer 1974)

- G. Johnson (Summer 1974)

Women were only 1.4 percent of the 101 new force members hired in 1974. These policewomen joined officers Paulette Dabbs, Janice A. Rzepecki, and Jane P. Marshall, bringing the number of policewomen to 18. (Grace Rowe, a policewoman hired in 1945, retired in 1974 and is not included in that total.)

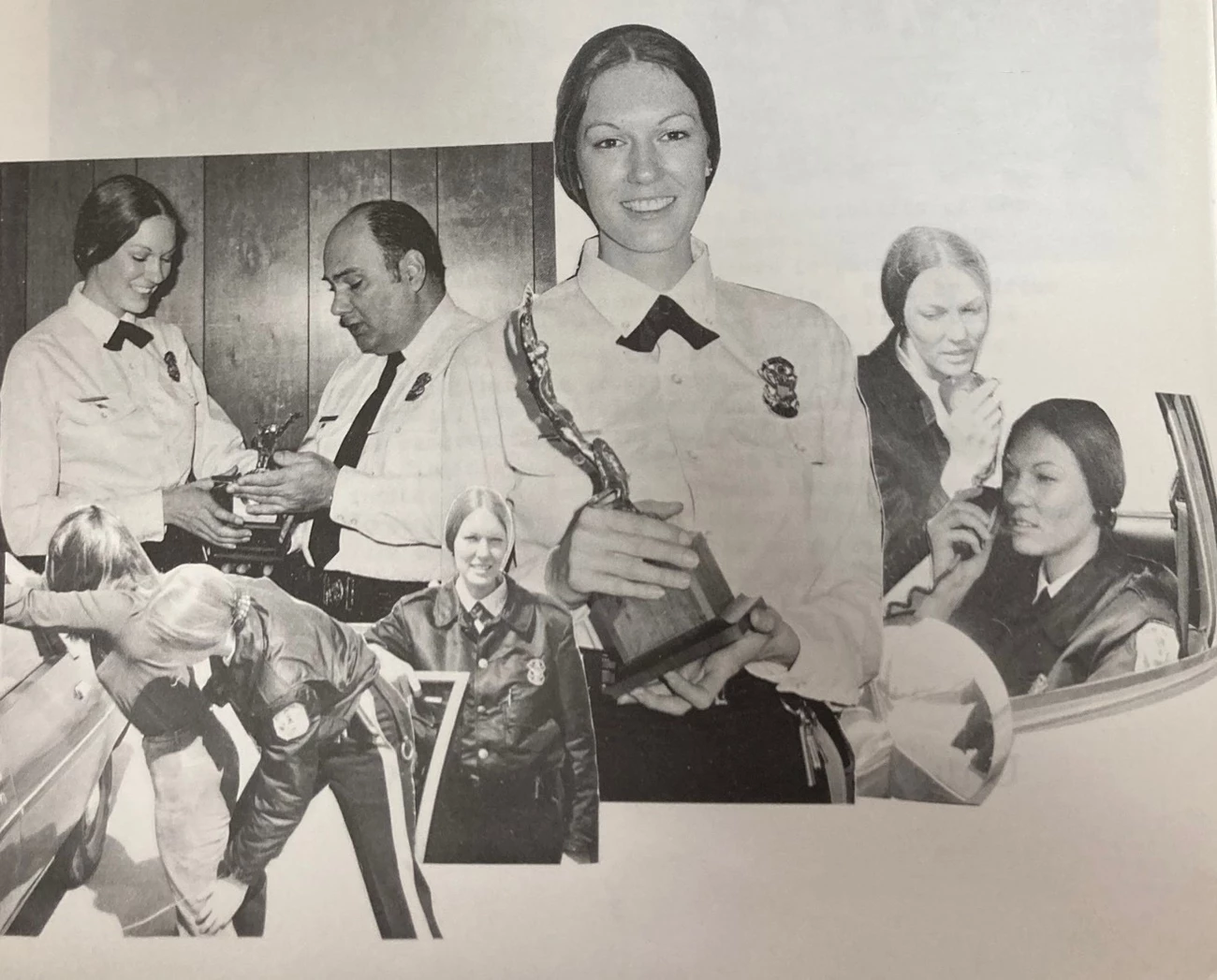

Women weren’t just joining the USPP, they often exceled. During her training, Casey Carlson achieved the highest scholastic score of any trainee at CFLETC to that point—scoring a total of 971 out of 1,000 points. She was awarded the Raymond L. Hawkins Memorial Award for Excellence in Police Training for her efforts.

The Changing Faces of the USPP

Although Simons recalled in a March 2019 interview that the USPP “didn’t want Blacks,” a third of the policewomen hired in 1974 were African American. These women—Simons, Winston, Johnson, Griffin, and Lee—may have been the first Black women USPP officers hired since Gertrude E. Wilson (1944 to 1966) became A Long-Awaited Asset. An unidentified Black woman pictured in the January to April 1971 CFLETC class photo may have been a USPP recruit, but that remains unverified. Two more Black women officers, Jacqueline Anderson (later Anderson-Parker) and Renee Jeter, joined in 1975 and 1979, respectively.

Maria A. Gonzales, the first Latina USPP officer, joined in late 1975. She attended Police School No. 54 from January to March 1976. Gonzales had a long USPP career, retiring in 2007 from the Internal Affairs Unit. Raquel Manso, the second Latina officer, joined the USPP on September 11, 1977, attending Police School No. 114 from September through December that year.

Other policewomen continued to be hired during the late 1970s including Pepper Karansky (1975), Valerie Fernandes and Patricia Horgan (1976); Roberta Hosmer (1977); Diane Maloney and Suzanne Inzerille (1978); and Phyllis Kowaloski, Catherine Hagan, Paula Hawkins, and Gretchen Merkle (1979). Although some of the women hired in the 1970s only worked a couple of years, many went on to decades-long careers with the USPP.

Ready or Not, Here We Come

Judy Shuster Ferraro’s description of the ad hoc way in which the policewomen’s uniform was developed in 1972 (see Measuring Up) suggested one way in which the USPP was unprepared for women officers. Another was the lack of facilities for women. Ferraro recalled, “The only difficulty was the men had showers; we did not. We had to use the women's restroom and use a sink to basically wash after [working out].” In 1990 NPS law enforcement specialist J.J. McLaughlin expanded on that theme, noting “They found that they had no locker rooms, no showers, or even private restrooms. They had to use the same restrooms that the public, even the prisoners, were using. In some cases, the women had to change clothes in converted closets which were much too small.”

Although women like Simons and Marshall recalled being encouraged by serving policemen to join the USPP, most faced some form of discrimination from supervisors or fellow officers. After completing the required year of foot patrol in early 1973, Shuster (now Ferraro) put in for cruiser patrol on the George Washington Memorial Parkway. She was told that the officer in charge of the parkway said that he “was not having a female on his parkway.” They promoted a man with less seniority instead. Shuster told management that if they didn’t reverse the decision, she would file a discrimination complaint. They relented and appointed her to the position she was entitled to and moved the officer with less seniority. In spite of this experience, Shuster recalled that most of the policemen she worked with “were great.” It was the men who she hadn’t worked with directly who “were the jerks.”

Recalling her experience, Simons noted that she was told, “You know, you would make a good officer. And right now, you would come in on the ground floor because they haven’t been hiring Blacks, and now they opened it up for Blacks…So, I decided to give it a try. Of course, they didn’t want Blacks on the Park Police even though they opened it up. So, I had to be a trailblazer. And being a trailblazer, I had to go through much persecution and challenges because they were trying to rule me out rather than take me in. So, I stood my ground, and I pressed my way and I made it in.”

As the only woman who attended Police School No. 114 (September to December 1977), Manso found that “it was tough being the only girl.” One instructor repeatedly sexually harassed her. She recalled that most of her supervisors accepted her, but some were “just male chauvinists, horrible, ugly people.” Often, it was other men who told them to “back off.” Over time, Manso noticed that white women seemed to be treated better than she was. “They were moved up ahead and things like that. I saw that and that was kind of troubling.” Her efforts to advance were stymied—she “never got selected. Either my paperwork was lost, or they couldn’t find it, or they never got it in time.” Years later, after she became a sergeant, a woman in personnel retired, and all of Manso’s applications were found hidden in the bottom drawer of her desk. Manso also suffered the indignity of being “renamed” Rachel because other officers claimed they couldn’t pronounce Raquel.

Karansky quickly found that being the first and only woman officer in the San Francisco Field Office had its challenges. She explained that “a lot of information got exchanged in the locker room and you weren’t privy to that. It’s like a men’s club in terms of how the assignments are made out.” In a 1980 Courier article she noted, “The biggest problem in working with the U.S. Park Police is that it is such a non-traditional male-oriented job, and the attitudes that men have are the biggest barriers you have to overcome. The easiest way I’ve found to overcome that is to try and ignore these attitudes and do the best job I can.”

Working Under a Microscope

The police stations were hotbeds of gossip about the policewomen. Ferraro recalled, “People that talk about women gossiping have never worked with men. Because let me tell you, they're ten times more malicious. And if you just had a cup of coffee with somebody, ‘Oh, they're having an affair.’ They were terrible about that.” Rumors that some policewomen were lesbians circulated without basis. The wives of male officers were sometimes jealous of a policewoman partnered with their husbands, creating further strife within the ranks.

McLaughlin wrote that many men objected to having women partners and “numerous sexual comments were made to frustrate the women to the point of leaving the police force.” Simons recalled, “During that time, men didn’t want women as their partners. They didn’t feel secure having them as their partners. The guys wanted to make you prove yourself, that you were worthy of being an officer with them. So, they wouldn’t help you in any kind of way, you had to make your own way. When they called for backup, you would be the last one to be called.”

McLaughlin also noted, “whenever a female officer made a mistake, it was because she was a woman. If a male officer made the same mistake, it was never because he was a man.” Ferraro also spoke of feeling like they were just waiting for the women to fail. Karansky recalled being disregarded and that other coworkers treated her more as a lady than a fellow officer. In one memorable instance, she recalled,

I stopped a car that was reported stolen. I was positioned behind the vehicle door with my gun drawn, waiting for my backup, when an off-duty officer drove up in his personal car, leaped out in civilian clothes and yanked the driver out of the car. He had no gun and no handcuffs for the guy he yanked out, and he was in direct line of fire from the other passenger. He made it necessary for me to endanger my life and his in taking those two men into custody.

Even after five years on the force Karansky was still scrutinized. In 1982 she recalled, “They continue to check on me. When I go on a special case with another guy, the other officers will go to him later and ask how I did, how I fought, how I handled myself. I’ve never once heard them check on a man that way.” Karansky had “passed all the same tests and took the same training [as the men officers].” She “wanted so much for them to like me, so I didn’t say anything. I just kept plugging away, working hard, and hoping someday they’d accept me for what I was—a police officer.”

As the 1980s dawned, more women police officers were expected, if not always accepted. Over the next few decades women extended their reach withing the USPP. Although their numbers remained small, policewomen continued to break barriers and were soon moving beyond foot and cruiser patrols, entering the Special Forces.

Sources:

“Discrimination Decision.” (1972, November 30). The San Bernardino County Sun, p. A-10.

Ferraro, Judith. (2022, July 22). NPS Oral History Collection, NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry Center.

Hill, D. (2019, March 26). A Women’s History Month Salute to Annie Simons. Praise 104.1. Retrieved July 13, 2022, from https://praisedc.com/1927056/a-womens-history-month-salute-to-annie-simons/

Internal Revenue Service. (1992). Women in Federal law enforcement. University of Michigan Library.

Mackintosh, B. (n.d.). National Park Service: History of U.S. Park Police. National Park Service. Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/police/police6.htm

National Park Service. (2000, Summer). “Class of 2000”.’” Arrowhead, volume 7, Number 3.

O’Flaherty, Mary. (1974, June 18). “New Arm of Law Needs Hand.” Daily News (New York), pg. B1.

Rose, Anna. (2016, May 19). “50 Years of Police Officer of the Year: 1990 First Female Awardee.” https://www.theiacp.org/news/blog-post/50-years-of-police-officer-of-the-year-1990-first-female-awardee, retrieved May 26, 2022.

United States Department of Interior. (1978). Doors to the Future: Careers for Women.

Retired US Park Police Association. (2016). United States Park Police 225th Anniversary. Acclaim Press, Moreley, Missouri.

US Park Police. (1974). Annual Report for the Year 1974. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

US Park Police Retirees Association. (n.d.). “US Park Police.” Retrieved May 20, 2022, from http://www.usparkpolice.org/citationsofvalor.htmUnited States Crime Rates, 1960-2019, retrieved at https://www.disastercenter.com/crime/uscrime.htm on July 18, 2022.

WIFLE Committee. (n.d.). Interagency Committee on Women in Federal Law Enforcement [Press release]. https://wifle.org/resources/1991-ICWIFLE/pdf/4-5.pdf

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.