Last updated: March 7, 2022

Article

The Road to Rainbow: Snow Removal at Bryce Canyon National Park

Snow Arrives

It’s nearly 6 a.m. and the park is covered in six inches of fresh snow. Through this sea of white, Plow Operator Kelton Neilson slowly drives his car past the darkened Visitor Center toward the Maintenance Yard. Snow crystals twinkle in the headlights beneath a clear, starry sky. It’s the start of a 10-hour workday, sunrise is less than two hours away, and there’s a lot of pavement to plow before then.

Though there’s a network of side roads at its northern end, Bryce Canyon National Park has one main road. It’s 18 miles long, and it never really stops climbing. Taking this road from the park entrance at the north end to Rainbow Point at the south end is an upward journey of about 1,350 feet. This elevation change means weather conditions can be very different at either end of this road. “I’ve seen it a lot where sun’s shining at the developed area, but you get to the top of the S-turns [Mile 8] and it’s a blizzard,” says Kelton, “And then I’ve also seen it flip-flop—sun’s beaming down south and it’s hammering the developed area. It depends on what the storm pattern is.”

Climate.gov

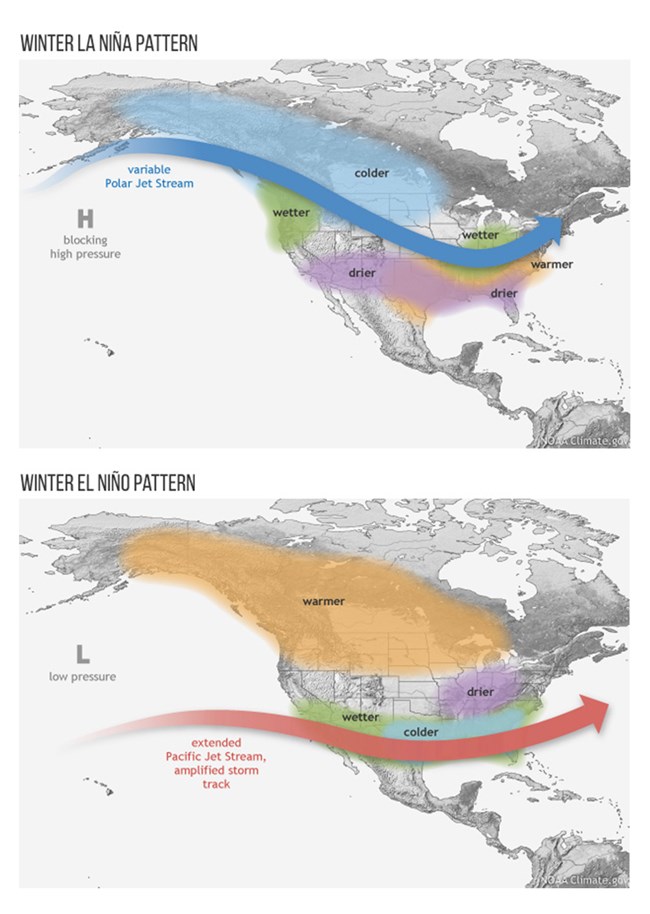

Roads and Trails Foreman Floyd Winder thinks his crew may have these patterns figured out, though they’re not sure yet. Theories concern the movement of the jet stream as it travels from the Pacific Ocean across the continent. In short, a jet stream that stays further north before diving south toward Utah should bring colder, drier snowstorms. La Niña winters tend to favor this pattern. A jet stream that comes from the south—typically the case in El Niño years—or even just dips south before reaching Utah should bring a warmer, wetter snowstorm. There’s also curiosity about whether these two patterns might deliver more snow to one end of the park than the other. Generally, though, the higher southern end of the park receives the greater portion of snow, usually at least 2-3” more per storm.

To predict whether the park is going to receive snow of any kind, Floyd spends a lot of time watching the weather. “I watch it like a hawk this time of year—I watch the radar, the Doppler, 3 or 4 news channels, NOAA, Weather Underground, WeatherBug. I gather four or five sources and put it together.”

When a winter storm is imminent and anything more than an inch or two is predicted, he’ll then schedule his staff to arrive at 6 a.m. before making the call to close the Rainbow Gate. Located at Mile 3 of the main road, this swinging wooden gate effectively seals off the southern 15 miles of the park until the snow has settled and the plows have cleared it. The priority is always the first three miles of the park. This area is typically called the “Bryce Amphitheater area” or the “developed area” and its network of side roads leading to viewpoints, trailheads, North Campground, the Visitor Center, and employee housing are the heart of winter park operations.

Plow Operations Begin

Two miles into the park, Kelton’s Toyota makes the turn toward the Maintenance Yard and the park’s fleet of snow removal equipment. Currently this fleet is comprised of two skid-steer snowblowers, a one-ton truck with a plow on it, a grader tractor, a front-loader with a snowblower attachment, and three ten-wheeler plows.

Of Roads and Trails’ six-person crew, Duane Sawyer, Troy Willis, and Ron Cooper primarily operate the skid-steers and the one-ton plow. The three ten-wheelers require a Commercial Driver’s License, and are usually driven by Rich Cropper, Lindsay Whitehead, and Kelton. They tend to use the same truck and get to know it best. Rich drives “Dino” (it’s over 30 years old and came from Dinosaur National Monument), Lindsay drives “Nickels” (three 5’s on its license plate), and Kelton drives “OPEC” (a bit of a gas guzzler).

NPS Photo

Keeping all this equipment operational through the winter is critical to keeping the park open. For Floyd this means making sure they have plenty of back-up parts on hand. Hydraulic rams that control plow movement have a way of blowing out. Shear pins on the snowblower do their job by destroying themselves rather than the blower, and hard snow and ice give them plenty of opportunities. For older vehicles, finding parts gets much harder. Dino’s fan clutch came from a junkyard in Indiana, and may be the last one they can find. Nickels’ 1997 wiper arm is discontinued with no after-market replacements. That might sound like a minor thing, but a single wiper is critical for driver safety and can make the difference between an operable and inoperable vehicle. These older plows are scheduled for eventual replacement, but even 12-year-old OPEC has challenges. Winter means plenty of work for the maintenance team and especially the park's heavy equipment mechanic, Derrick Conroy, to keep the fleet operating at full capacity.

Thankfully this morning all three ten-wheelers are functional, and shortly after 6 a.m. Dino, Nickels, and OPEC begin to rumble down from the Maintenance Yard. Plow blades are lowered and begin to loudly scrape. The temperature is still down near zero. Inside the plow cabs, temperatures are practically balmy, though. To keep snow spray melted and reduce strain on the wiper blades, drivers keep the windshield hot by cranking the heater as high as it will go. Former Plow Operator Royce Pollock would often be seen driving past in a swirl of snow, wearing short sleeves, a small hula dancer affixed to the dashboard.

As they reach the main road, both Dino and Nickels turn off to the north and plow to the park entrance sign at Mile 0 then back to the Maintenance Yard turn at Mile 2. Dino then returns north to clear the Visitor Center area while Nickels begins to plow a path to Sunrise Point.

NPS Photo

Meanwhile, Kelton turns OPEC south and plows to and around Sunset Point before continuing south to clear the roads to Inspiration and Bryce Points. As plows reach these viewpoint parking lots, radio traffic starts to crackle across the park. “213, 214, I’ve got a spot for you here at Sunset Point”. This is Kelton letting Troy know that he’s cleared a path for his pick-up truck and skid-steer on a trailer to unload and start blowing. This well-choreographed workflow gives park staff and early-bird visitors access first to the Visitor Center and Sunset Point, followed by Sunrise, Inspiration, and Bryce Points.

Since the Visitor Center requires staff to open at 8 a.m., Duane uses the 1-ton plow to clear the park’s residential areas and give morning commuters a clear path to the main road. He then clears the Mixing Circle area and provides access to fire hydrants in the Lodge and General Store area should any fire emergencies arise. North Campground is plowed last so as not to disturb campers until at least 8 a.m.

While the Roads and Trails crew focuses on clearing the park’s primary roads, much of the detail work in the developed area is handled by the other half of the park’s Facilities Management division: our Buildings and Utilities staff. In winter this includes Supervisor Dale Pollock, Maintenance Workers Moyle Johnson and Wayne Sawyer as well as Custodians Laura Martin and Dennis Greening. They too have a skid-steer blower and a smaller tractor with a blower mount. They use good old-fashioned shovels too, and assist with clearing the Visitor Center Plaza, North Campground campsites, employee driveways, and odds and ends like roadside pull-outs, Mossy Cave and other small areas.

On a good day with functional equipment and no additional snowfall, all of this can be finished well before lunchtime.

NPS Photo

The Visitor Experience

One thing you’ll notice as you drive into the park in winter is that as soon as you pass the park entrance sign the road goes from black to white with compacted snow. During a typical winter, most of the first three miles of the park’s road will probably look this way. Kelton admits he finds it a little embarrassing, as it looks like they aren’t doing their job. But there’s good reason for it. State roads are black because of road salt. The Utah Department of Transportation deploys 215,000 tons of salt per year to melt ice and snow from state roadways like SR-63 north of Bryce Canyon. Unfortunately, this salt can kill roadside plants and attract wildlife onto the road, both reasons the park opts to use rock cinders instead. If no one drove on them for a day or so after the plows passed by, park roads would melt completely too; but because vehicles quickly compact it and turn much of the snow to packed ice, it melts much more slowly. The fact that the Rainbow Gate is closed to all vehicles allows much of the park road beyond Mile 3 to melt clear.

Rock cinders won’t melt that compacted snow, but they do provide enough traction to make a big difference on hills, at stop signs, along turns and shady spots—anywhere there could be a possible slide-off or the need to stop. Unfortunately, cinders aren’t always enough to keep a vehicle on the road. Near the Rainbow Gate, the hill near the Lodge, the road to Bryce Point, and the hill above the fee booths are all known trouble spots. “Cars can make it, drivers can’t,” is how Kelton sees it, “I drive generally a 2WD car. That’s what I drive up here usually every snowstorm”. He concedes that if it’s two feet of snow, he’ll probably need to bring the truck, but adds that “our plow trucks aren’t four-wheel drive. They’re rear-wheel drive only”. The most common reason for “slide offs” cited, from the Roads and Trails crew to the Law Enforcement rangers that are called to assist, is speed. The difference between a car that stays on the road and one that leaves it is almost always a matter of simply slowing down.

NPS Photo

Parking lots and viewpoints have challenges of their own, from cars following plows too closely (they do a lot of work in reverse) to pedestrians wanting to be covered in skid-steer-blown snow. “With the blowers they want to go stand underneath your chute. What they don’t understand is that rocks are a lot of times in the snow, ice balls are in it. They think it’s soft and fluffy—it’s

not”.

If it’s especially wet snow, that’s hazardous for park signage. “We have a lot of soldiers go down,” Kelton admits, “We don’t try to break them”. Ultimately the Roads and Trails crew at the same ones responsible for replacing these signs, and that’s hard enough work. “I don’t know if you’ve dug many holes out here, but it’s not fun digging. You don’t go very far and then you hit rock”.

NPS Photo

Turning South

Once the roads, viewpoints, parking lots, and fire lanes are completely cleared of snow, OPEC, Dino, and Nickels turn their plows beyond the Rainbow Gate. Dino takes the yellow center line. Behind Dino, OPEC pushes snow to the white line on the right, while Nickels favors to the left of the yellow line and pushes snow that way. Previously plowed snowstorms create berms on the side of the road that make it easier to tell where this is, though the long stretch of road through the meadow at Mile 4 is known for its wind-blown drifts. Orange poles mark turns, curbs, and other barriers. Mostly it helps to have years of experience with this road.

At Mile 6 they reach the first viewpoint. Here at Swamp Canyon, Nickels falls behind to clear the parking lot as the other two push on up the S-curves. The leap-frog pattern continues: OPEC falling behind at Farview Point’s parking lot while Dino pushes on to Natural Bridge’s. By this time, Nickels has finished Swamp Canyon and continues to push south past Natural Bridge to Agua Canyon, and so on all the way to Rainbow Point. Behind them, skid-steers wait for word over the radio, then progress viewpoint to viewpoint, doing the finer detail snow removal around sidewalks and railings.

If weather permits and all three plows are working, the entire park can be plowed and the Rainbow Gate could be reopened in a single day. But when equipment fails, or one snowstorm is followed by another, efforts remain focused on the Bryce Amphitheater while the snow grows ever-deeper down south. Even when no new snow falls, whatever’s on the ground is always being reshaped by the wind. Areas like the 4-mile meadow and the area burned by the 2009 Bridge Fire along Whiteman Bench typically have the worst drifting. On tight corners cut into slopes, drifting can quickly create snowbanks 4 to 5 times deeper than the average snowpack in the area.

Once snow depth gets beyond a few feet, or its particularly wet snow, plows aren’t able to push the snow from the road. In times like these, the front-loader with the snow blower attachment has to drive down from the Maintenance Yard. It’s an effective tool, but a much slower-going one. During the 2018-2019 government shutdown, crews weren’t able to plow beyond the Rainbow Gate for over a month. Then, shortly after the shutdown ended, four snowstorms arrived back-to-back. Then it rained a bit, too. This created conditions that required the front-loader to take the lead all the way from the Rainbow Gate to Rainbow Point. Working every day, those 15 miles took a month and a half to clear.

NPS Photo

The front-loader’s blower creates a box-shaped path through the snow, rather than the sloping edges left by the plows’ thrown snow. These shear edges then require the grader tractor’s help. Once it arrives from the Maintenance Yard it can lift its broad central blade and knock the tops of these snow walls down to a height that the plows can begin to toss snow over them again. Since this can greatly slow the operation down, the Road Crew will begin opening the sections they’ve finished in stages. First it can open to Mile 10 at Farview Point, followed by Natural Bridge at Mile 12.5, and Ponderosa Canyon at Mile 15—viewpoints with parking lots large enough for RVs to turn around.

Being able to work without worry of other vehicles on the road helps the work go as fast as possible, and on average the Rainbow Gate only remains closed for a day or two following a single snowstorm. Asked if they felt it was worth the effort to remove snow from Miles 3 – 15 of Bryce Canyon National Park every snowstorm, Kelton and Floyd agreed it was. The work feels worth the effort, and is a welcome change of pace during the year. “I like the winter. I like summer too. It changes it up,” Kelton reflects, “Don’t get me wrong—day after day snow, it wears on you,” but even so “I hope we get three or four more feet!”

Making the Dream Possible

For the first 10 years of its history as a national park, Bryce Canyon simply wasn’t open in winter. Fee booths would operate May through August, and the park itself was only open six to eight months of the year. This all changed in 1938, when an agreement with the State Road Commission arranged for the park road to be plowed by state road crews. At some point later, by the mid-1950s at the latest--the park had its own snow plow for these purposes.

Today, experiencing Bryce Canyon all the way to Rainbow Point in winter is a dream for people all around the world. That dream is possible because of the equipment and the expertise we have in our Facilities Management division. If you'll be visiting the park November through May, we recommend keeping an eye on the park conditions by visiting Bryce Canyon's Current Conditions page as well as the helpful tips at the park's Visiting in Winter page. For road conditions leading to and from the park, we suggest visiting Utah Department of Transportation's Traffic Page.

NPS Photo