Last updated: February 26, 2025

Article

The Battle of Bunker Hill

Every year, community members and the general public gather at the Bunker Hill Monument to remember the events of June 17, 1775. The granite obelisk marks the site of the battle known as "The Battle of Bunker Hill." Here, hundreds of British soldiers and colonial militia fought and died during the first major battle of the American Revolution.

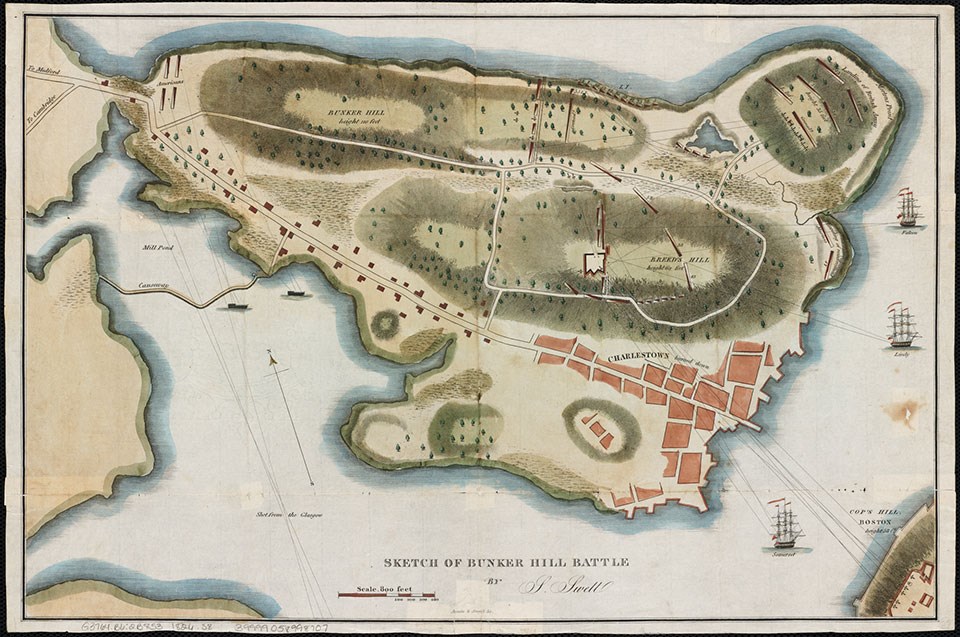

This battle took place throughout the hilly landscape and fenced pastures of Charlestown, a town just north of Boston. While named after the highest hill in the area, Bunker Hill, the battle took place on Breed's Hill, the hill situated closest to the Charles River.

The battle between the forces of the British Crown and those of New England lasted around two hours. Yet, it sent shock waves through Charlestown, the surrounding towns, and the colonies.

"View of the city of Boston from Breeds Hill in Charlestown / del. & engraved by S. Hill." Library of Congress.

Prelude

During the 1760s and the early 1770s, tensions rose between Parliament and the colony of Massachusetts. For years they clashed over unpopular taxes, occasionally resulting in physical altercations.

To stem further violence, Massachusetts' new royal governor, General Thomas Gage, took steps to prevent colonial militia from raising arms against the Crown. Local militias responded. They quietly began stockpiling arms, ammunition, clothing, and other essentials in towns such as Concord, west of Boston.

Having learned of the Concord stockpile, Governor Gage sent 700 troops to the town in April 1775.[1] Colonial militia met Gage's forces in Lexington and Concord. This conflict on April 19, 1775, marked the beginning of the American Revolution.[2]

Click on the image to explore map.

Courtesy Boston Public Library, Norman B. Levanthal Map Center and Library of Congress

Word of this engagement spread throughout the colonies. An estimated 20,000 militiamen made their way to Massachusetts, anticipating another clash.[3] They came from the nearby colonies of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire. These individuals included white colonists, freed and enslaved African Americans, and Indigenous peoples.[4] This army of New England forces aimed to contain the British military inside Boston. As forces encircled the town, thousands of citizens sought to escape this siege.

By the end of May 1775, British reinforcements arrived to break the siege. This plan included seizing two of the heights outside of Boston: Dorchester Heights to the south and Charlestown Heights to the north. Leaders of the New England militia soon received word of this plan. On the night of June 16, the militia prepared to fortify Bunker Hill on the Charlestown Heights.

Opening Moves

Around midnight on June 16, hundreds of colonial soldiers used pickaxes and shovels to construct an earthen fort, or redoubt, atop Breed's Hill, a hill southeast of Bunker Hill. These troops also reinforced a New England-style fence of stone and double wooden rails that ran north from the hill towards the Mystic River. Their leaders, Colonel William Prescott, General Israel Putnam, and Colonel Richard Gridley instructed them on how to build the defenses.

Courtesy Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center

Click on the image to explore map.

As the sun rose, General Thomas Gage and his officers in Boston saw the newly built redoubt on Breed's Hill. Around 9:00 a.m. they met to decide on a plan of action.[5] Gage instructed General William Howe to lead British troops across the Charles River in an assault on the redoubt. Meanwhile, the British Navy fired cannon from their ships off the coast of Charlestown toward the redoubt. This cannon firing started at first light and lasted two hours.

The British forces faced many challenges as they sought to land at Charlestown and take Breed's and Bunker Hills. First, they had to wait until midday for the tide to rise so that their Navy could ferry roughly 2,400 troops across the Charles River to Charlestown.[6] The British regulars next had to face Charlestown's swampy terrain and an enemy already dug in. Additionally, sailors aboard British Navy ships could not provide their troops with adequate cannon fire coverage to protect them in the field. The shallow waters and low tide prevented ships from getting a clear aim of the colonial position.[7]

The Attacks

With the delays in the British forces' attack, additional colonial forces arrived. These reinforcements helped fill gaps in the colonial defenses. In anticipation of combat, colonial officers prepared their troops who lacked combat experience. Several officers planted stakes in the ground beyond their defenses to mark at what point their soldiers should fire upon the British Redcoats.

Around 3:30 p.m., General Howe advanced his troops towards the colonial defenses. Some attacked the redoubt, breastwork, and rail fence. Another force moved along the beach on the Mystic River in an attempt to bypass the rail fence, flank the colonial defense, and attack the rear of the redoubt. Unknown to Howe, colonists barricaded the beach and stopped the British troops in their tracks.

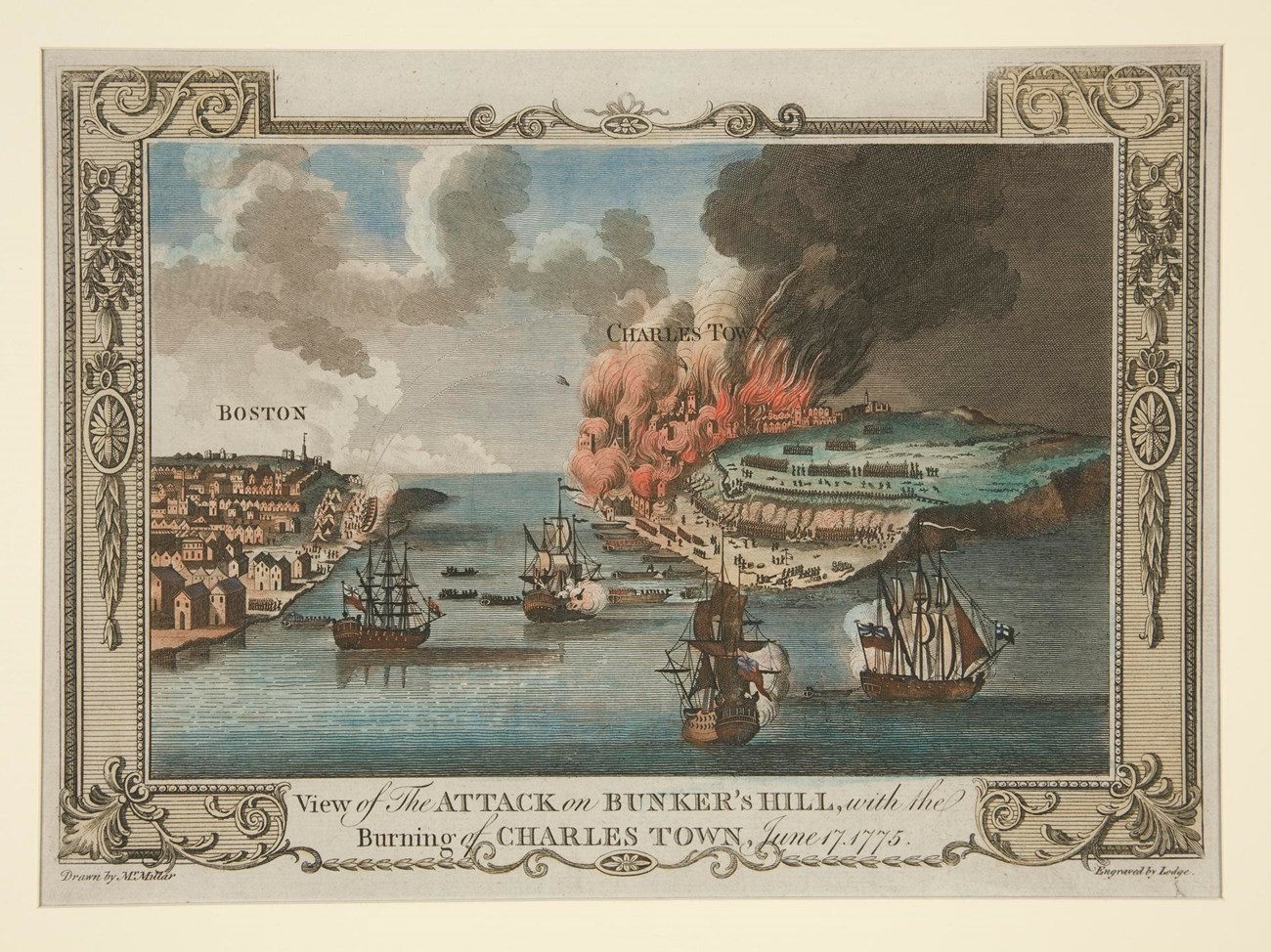

Courtesy Library of Congress

The musket fire proved devastating when the advancing British came into range. The pasture that was supposed to be the avenue for a flanking attack became a pen of slaughter. On the hill, fire from both the redoubt and from buildings at the edge of the abandoned settlement of Charlestown harassed the feint attack as well. At one point Prescott ordered his men to cease fire. Uncertain whether the colonists had fled the redoubt, British units marched closer, only to receive another heavy volley of fire. Meanwhile, British gunners trained their cannon on the abandoned town and set the buildings ablaze with red-hot heated cannonballs to drive out skirmishers at the edge of town

Howe was forced to order a withdrawal when all momentum was lost. After regrouping his forces and incorporating reinforcements, a final assault marched to the left of the redoubt rather than the right. As the British forces increased pressure upon the redoubt, men inside were exhausted and running desperately low on ammunition. As British soldiers and Marines mounted the walls, they engaged with bayonets in a bloody melee inside the redoubt. Any colonist able to flee ran as the British pursued. The British forces gave chase as far as the next hill—today's Bunker Hill. Survivors and forces that never engaged regrouped on the mainland on hills opposite Bunker Hill. Both sides awaited a counter-assault or follow-up attack. Neither came.

Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, Yale University Art Gallery.

The Aftermath and Legacy

After two hours of combat, British troops casualties totaled 1,054. Colonial losses totaled an estimated 450 soldiers by comparison.[8] When the smoke cleared, the town of Charlestown laid destroyed. Residents were forced to move or start their lives anew.

News of the battle helped unite the thirteen colonies. In the aftermath of the battle, General George Washington assumed command of the colonial forces around Boston in July 1775. Washington had been appointed by the Continental Congress to lead a new Continental Army in June 1775.[9] This army ultimately forced British troops to evacuate Boston in March 1776.

The Battle of Bunker Hill has inspired generations to consider what it takes to stand up for one's liberties. Abolitionists, suffragists, labor activists, and others have referred to the battle and its monument in their own fight for liberty and justice.[10] Today, we are asked to question what the battle and its Monument means to us as we strive to actualize the country's founding ideals.

Video Series

-

Bunker Hill (Part 1): Prelude to the Battle

Join Ranger Patrick in an overview of how the Battle of Bunker Hill came to happen on June 17, 1775 across the hilly pastures north of Boston.

- Duration:

- 7 minutes, 47 seconds

-

Bunker Hill (Part 2) "One Step Further"

Ranger Patrick explores how the battle unfolded on June 17, 1775.

- Duration:

- 11 minutes, 53 seconds

-

Bunker Hill (Part 3) "The Decisive Day"

Join Ranger Patrick for our concluding installment in our three-part series about the Battle of Bunker Hill and its aftermath. Learn about how the British were eventually forced to evacuate Boston on March 17th, 1776.

- Duration:

- 10 minutes, 22 seconds

Footnotes

[1] Kevin Phillips, 1775 A Good Year For Revolution (New York: Penguin Group, 2012), 10; Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds., The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 66.

[2] Learn more about Lexington and Concord by visiting Minute Man National Historical Park's website.

[3] Bernard Knollenberg, "Bunker Hill Re-Viewed: A Study in the Conflict of Historical Evidence," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 72 (1957), 86-87. Knollenberg cites a letter from Nathaniel Greene to Governor Cooke of Rhode Island, June 28, 1775, and estimates the New England forces around Boston at 19,790: Massachusetts 13,600, Connecticut 3,000, New Hampshire 1,800, and Rhode Island 1,390.

[4] To learn more about the African American and Indigenous soldiers who fought at Bunker Hill, please see Patriots of Color.

[5] General William Howe to Admiral Richard Howe, letter, Charlestown, MA, Camp upon the heights of Charlestown, June 22 and 24, The Journal of the Proceedings of his Majesty's Ship Somerset, George Curry Commanding, 1774-1778, Log of the Somerset, National Public Records Office, Kew Gardens, London, England.

[6] Paul Lockhart, The Whites of Their Eyes: Bunker Hill, the First American Army, and the Emergence of George Washington (New York: Harper Collins, 2011).

[7] Lockhart, The Whites of Their Eyes, 68, 217; Richard M. Ketchum, Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill (New York: Holt Paperback, 1999), 126.

[8] General William Howe to British Adjutant General, letter, June 22 and 24, in The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six, 131; General George Washington to brother John Augustine Washington, letter, July 27, 1775, in The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, ed. John Clement Fitzpatrick and David Maydole Matteson (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1970), 372.

[9] "George Washington's Commission as Commander in Chief: Primary Documents in American History," Library of Congress Research Guides, accessed June 29, 2024; "Siege of Boston," George Washington's Mount Vernon, accessed June 29, 2024.

[10] To learn more about the memory surrounding the battle and the Monument, please see Bunker Hill Memory.

Bibliography

Commager, Henry Steele, and Richard B. Morris, eds. The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants. New York: Harper & Row, 1975.

Hagist, Don N. These Distinguished Corps: British Grenadier and Light Infantry Battalions in the American Revolution. Warwick, England: Helion and Company, 2021.

Ketchum, Richard M. Decisive Day: The Battle for Bunker Hill. New York: Holt Paperback, 1999.

Knollenberg, Bernard. "Bunker Hill Re-Viewed: A Study in the Conflict of Historical Evidence." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 72 (1957): 84-100.

Lockhart, Paul. The Whites of Their Eyes: Bunker Hill, the First American Army, and the Emergence of George Washington. New York: Harper Collins, 2011.

Oliver, Peter. "Bunker Hill." In Peter Oliver's Origin and Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View, edited by Douglass Adair and John A. Schutz, 123-127. San Marino, CA: The Huntington Library, 1961.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution. New York: Viking, 2006.

Phillips, Kevin. 1775 A Good Year for Revolution. New York: Penguin Group, 2012.

Quintal, George. Patriots of Color: "A Peculiar Beauty and Merit": African Americans and Native Americans at Battle Road and Bunker Hill. Washington, D.C.: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, 2004. Also available online: Patriots of Color.