Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Texas Parks & Wildlife Cultural Landscapes

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

Michael Strutt: I'm the director of cultural resources for parks and wildlife, so we manage your state parks. And at TPWD, we own and manage over 600,000 acres in the state, encompassing nearly 90 state parks across many varied cultural landscapes throughout the state.

Our mission statement is to conserve those resources within all that acreage and give access to the public for their enjoyment and their education. The landscapes that we manage for you, I'm assuming that most of the folks in the room are Texans, but even people from out of state, these state parks are for the general public. So we manage these things for the public, from the Piney Woods of Northeast part of the state, to the deserts of the Big Bend, to the canyons of the Panhandle to the brush country, deep South Texas along the Rio Grande. We manage lake shores and seashores, rivers and places of water recreation and water conservation, specifically for the conservation of water. We also manage places of sunsets and of contemplation.

Some of these landscapes are iconic, from the monolith that is Enchanted Rock, which is also on the National Register of Historic Places for its prehistoric archaeological resources at the park, to the designed landscape of Bastrop State Park, a National Historic Landmark for the integrity of that landscape designed by the National Park Service and built by the Civilian Conservation Corps or the CCC in the 1930s.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

We also have iconic buildings such as the Mission at Goliad and the mission of Mission Tejas, which are both reconstructed buildings, but they are part of the historic landscapes that we interpret to the public. These places, the landscapes and the built resources within them, all tell the story of Texas.

The first state park dedicated to recreation, Mother Neff State Park is named for the mother of former governor Pat Neff. Here's a picture of Mrs. Neff and her son Pat, sometime in the late 19th century. But the park land that she donated, which is named for her, is on the National Register of Historic Places. We use the National Register and National Historic Landmark designation to help us elevate the image and the perception of these landscapes to both the public and to our own staffs.

These places are educational and uplifting. They are emblematic of the state and create a sense of place, both of and in that location and for what Texas is in her public's minds. Sense of place is very strong in Texas and Texans, and the state parks embody that feeling. As a quick example of that, I was doing a little bit of research on the internet about Texas state parks to see what else was out there outside of our own webpages, and a website called Great American Country, 20 places to visit in the state of Texas, 14 of them are state parks.

But the public mostly wants to come and play in our landscapes and enjoy the outdoors, and why not? Texas manages some of the best of the state. My discussion with you today about cultural landscapes will focus on how we manage change within your landscapes, and I'll highlight our successes and challenges as well as some of the needs that we have concerning cultural landscapes and the way the research that we do helps us to manage that change.

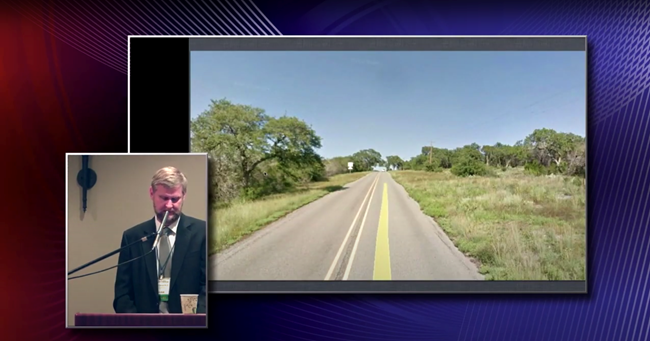

Mother Neff is a rural historic district that includes the river road running beside the Leon River in Coryell County. The section of the road running through the park is a contributing element to the district because of its bucolic tree lined viewscape, which you see here. This is an image from 1992. Some of our parks' neighbors understand the beauty of this road and the fact that it's a National Register site, and they want it maintained as such, but mother nature has her own designs for Mother Neff.

One need is that we have not assessed most of the landscapes and the parks for integrity and significance. We have not gone through that process that you heard Robert talk about this morning. We have conducted a handful of assessments on a few of the parks, designed mostly by the National Park Service and built by the Civilian Conservation Corps, and some of the parks are on the National Register, as I mentioned a moment ago. Among those that we have assessed are Mother Neff, Abilene State Park and Park Road 4, which connects Longhorn Caverns and Inks Lake State Park.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

While this nomination was written in ‘92 and you see these trees, since then a number of the trees have been lost to flood. Sometimes this park goes under water for as much as six months at a time, and then there are periods of drought. So, we are losing part of that bucolic landscape simply through mother nature's elements and her change. And then we also lose trees because they grow out over into the road, and for vehicle safety they have to come down.

Another significant road within the system is Park Road 4, which I mentioned a moment ago. It's a 15 1/2 mile long, 100 foot wide road and right of way constructed as a parkway, connecting two of our state parks and two state highways. The road was designed with the concept of getting there is half of the experience. It is a parkway. The speed limit is slow, encouraging everyone to slow down and enjoy the scenery. This park road was designed by the park service and built again by the CCC in the 1930s.

We did an assessment, we had a cultural landscape report written and a National Register nomination written because of a nexus of events and needs within that road and those parks. A road maintenance contractor had damaged one of the walls along the road in an area where the walls were covered with vegetation. Because of that, we realized that we did not know where all the landscaping elements were along the road. At the same time, a radio broadcast company wanted to construct a 400 foot transmission tower to be able to reach both Austin and San Antonio at the very foot of Longhorn Cavern State Park.

Another issue that we have started to contend with is neighboring land owners whose property adjoined what we have along the roadway is only a 100 foot right of way, they want to build their large Texas style gates for their properties. As the adjoining properties pass from one generation to the next, former ranch land becomes subdivided. So this area is becoming less and less rural and more and more suburban, although not quite the suburban that you saw in Houston or Austin earlier. Rather than dense housing, it is becoming more one and two houses here and there. But what that does, is it creates road cuts and these kinds of elements along what had been a Parkway or still is a Parkway, it's just that these are now intrusions into that landscape.

And finally, because of all of that development happening along the road and the two highways that this road adjoins, TxDOT had plans to widen the two-lane parkway into a five-lane major highway to connect those two roads. So for us, there were these combinations of issues. We instituted this cultural landscape report (CLR) and National Register (NR) nomination to help us manage and stave off some of that kind of pressure.

So, both the CLR and the NR were completed in 2007, and to this day, the road remains a two-lane parkway. There is no large radio tower. The broadcast company called me up and asked, "So tell me about how this National Register nomination is going to affect me and building a radio tower at the foot of your park but on private property." We had about a 20 minute conversation, I've never heard from the gentleman again and we don't have a radio tower, I'm happy to say. So the National Register does help.

However, there is nothing TPW really can do to slow the rapid growth and private land sales. The best we can do is manage the road and the parks to continue them being in an oasis amidst the growth. The CLR and the National Register nomination were a result of several challenges coming from outside and other entities, and the outcome was the success of maintaining our parkway design. But we continued to face the challenge of expansive regional growth.

Turning to Abilene State Park. We contracted with a historian to conduct a cultural landscape inventory as a way for us to understand the evolution of that park and in an interest to do some restoration of that cultural landscape. What we learned from this exercise is that the park has changed quite a bit over time. So what you see here is a map from the National Park Service and the design intention from 1935.

The important thing to notice about this plan is here is the center of the park. The blue line is the park boundary, and there was a circulation road around the park, it's a one way road, it was intended to give the visitor a very specific experience as they came into the park and they went through woods into open glades, back into woods, dappled sunlight, a pool in a recreation area within the park.

So here it is in 1940. Here is that one way design road. Don't look at me, look at the pretty pictures. So the development area with the pool inside the park and then the blue line is the boundary of the park.

Here we are in 1971 and you can see that there have been a number of changes to that design. These blue lines are new roads that have come in. The entrance has changed and the yellow is part of that circulation. That part of the road has actually been taken out.

Here we are in 2004. New camping theory, circular campgrounds because of the size of recreational vehicles having changed and gotten larger. I'll talk a little bit about that some more in a minute. Our circulation road does not work now.

These are the ways that the visitor comes in and experiences that landscape. I give a half day module with my staff on cultural resources in the state park to our new superintendents, assistant superintendents, and I talk about this park. And I also talk about this to our project managers and our infrastructure division. What I used to say to them is that this park really no longer is eligible in our mind for the National Register. And that didn't resonate with people. It was a, "So what?"

So, I've changed the message. Robert talked earlier about how when you speak with people who don't understand cultural landscape, sometimes you can be speaking French. I changed my language, I went from French to Polish. I have a Polish background, that’s my ethnicity. And believe it or not, people started understanding that when I started saying, rather than it's no longer really eligible for the National Register, but we have significantly altered the visitors experience here. They get that. So in the communication of what cultural landscapes are to other folks, finding what resonates with them is what works for us.

So, while we admit that the landscape has significantly changed over time, some of those changes occurred within just a few decades of the park opening, and as you saw there in the early 1970s, there's no one looking out for cultural landscapes at Texas State Parks. It was just a fledgling discipline. However, today there is a robust cultural resources program in the state parks and we operate mostly behind the scenes. I have with me today a couple of our folks.

A couple of our regional guys who help look out for these landscapes out in the parks. We operate mostly behind the scenes. The public does not see us on a day to day basis. They see the ranger in the TPWD green uniform, but it's our CR staff that pays attention to the things like the landscapes and the use of historic preservation principles.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

So, what I'm showing here is the management structure at Parks and Wildlife. It's 1300 people that are running your state park system. And not everybody there is going to understand cultural landscapes as the CR program does. And this is not a criticism of our colleagues in any ways. It highlights the fact that we all have different strengths in our training and backgrounds, and it takes a number of different perspectives to run a state park system. And let's face it, cultural landscapes is a nuanced concept. Not everyone is trained to look at these places in the way this assembled group does.

The CR staff help our operations side manage change and they all trained as archeologists, though we refer to them as Cultural Resource Coordinators because we expect them to see a broader picture of culture and resources and not just the boundaries of an archeological site.

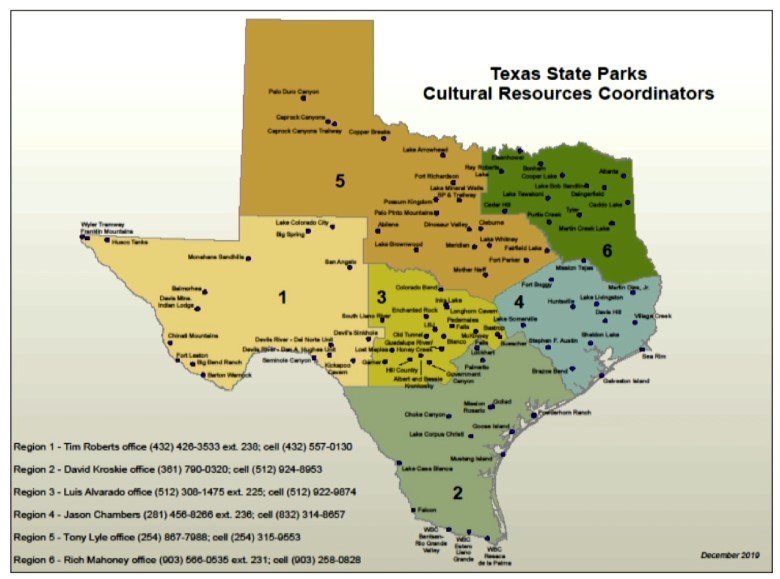

So, this is the map of the regions that these folks all handle, and within each region, each one of these RCs, as we call them, manages between 15 and 20 parks. They are housed in our regional offices and they work directly with the park superintendents, the maintenance staff and construction managers by reviewing any proposed project in a park. We have a form that any project manager must fill out and it is called, simply enough, a project review request. This form and review process is akin to a process borrowed from the National Park Service, which many years ago when I worked in it, had the rather risque name of the Triple X Process.

So, the RCs review projects and help guide new developments to manage parks and cultural landscapes through change. We fully realize that landscapes are evolutionary things, they are not static. Besides the plants that come and go, visitation has an impact on the parks.

So, today's camper has different requirements than in days past. Campgrounds used to be simple, a place to put your car, a tent, maybe a small camper and a bathroom down the way. The campsites were typically small and spread out with space in between. For decades, camping itself was fairly simple. But the units really began to grow by the 1970s. I showed earlier in the new theory of campground development.

While some campers are returning to the teardrop shape of old, the trend is to continue to increase in size. Today's users can be very different with different needs from their campground. The behemoths that ride the road today require much more room and electrical hookups. The size of the campgrounds and the roads to handle these machines have to increase for these machines. We also have to increase the size of our bridges. We have to increase the load capacity of our bridges that have been around since the 1930s because people are coming in with very large, very heavy equipment.

We can all argue that staying in one of these is hardly camping. A lot of people call this glamping. These machines are better than any luxe hotel room, if for no other reason than nobody else has ever used that toilet, right?

The point is that these machines impact the way our highly designed landscapes from the CCC era function. Those landscapes and the elements within them are getting bigger. The numbers of visitors to the parks themselves have increased substantiallyjust in the last decade. We try to accommodate the demand by adding new services and amenities to the parks. These additional elements in a park change the look and feel of a landscape.

So, the RCs work to manage that change. In preparing for this paper, we had an electronic discussion. I showed you, they are all staged out about the state and I'm in Austin, so we had an electronic discussion. How do they individually manage the projects and the people? Again, speaking French or Polish, how do they manage the parks and the projects that they are reviewing?

The review process is based on the RCs' knowledge of the parks and the landscapes. Archeologists are good in this respect because they are trained to get out into the woods and the weeds to do their work. They use GPS to record what they find and sometimes while dragging their shovels and screens through the woods, they find remnants of the CCC era, the ranching era or any other previous uses of land prior to the property becoming a state park.

But many of the projects they review are in or near already developed parts of the parks. Their decision-making process on how to manage change is done on a case by case basis. Park staffs or construction project managers propose additions or changes in order to create new or update facilities. The challenge lies in the fact that we need additional changes to the landscape for safety, rules updates or things of that nature. But there isn't necessarily a compelling reason against those changes other than it's a change to a design landscape and we can end up with a landscape's death by a thousand cuts, otherwise known as cumulative effects.

Some of our project designers think the idea of a cultural landscape is a very abstract concept when they can see up to 80 years of evolution and change over time. That is one of our challenges. The projects being reviewed can either be large scale or small and it is the small ones that frankly we struggle with most conceptually while dealing with our colleagues.

Small things like visible soda machines are some of the issues we want to avoid. Yet, if they are not visible, the customer doesn't know where to find a drink for purchase. Soda machines and signs, like you see here are probably the two things we most often wrestle over. One technique we use to persuade our folks not to add to cultural landscapes or conversely why and how to hide things like soda machines is the concept of view sheds. We heard Robert talk about the difference between view sheds and viewpoints earlier today. We can convince others that interrupting the view shed diminishes the experience for the visitor. We realize that such a tactic of course is particularistic. It is concentrating on a single element of a landscape, but that works for us much of the time, especially in the smaller parks where visitor amenities are concentrated and your viewscapes and viewsheds are concentrated.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

Even though our largest parks are still much smaller than national parks, we do have a couple that are fairly large. The one exception being Big Ben Ranch State Park at 315,000 acres. But even there, use is concentrated in specific areas of the park. This property was developed mostly within the last decade, and so we tried to, from the outset, put our campsites and other amenities out of line of sight with each other and away from prehistoric and historic elements of the landscape.

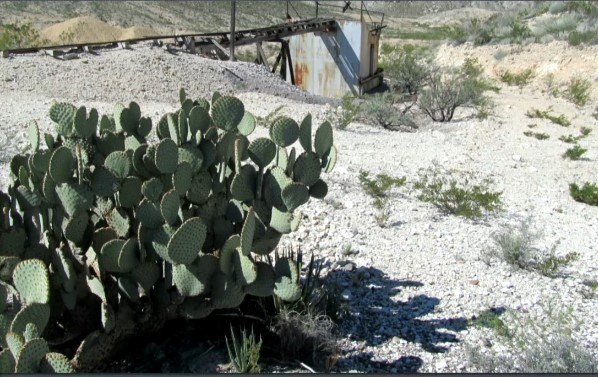

The park itself is a palimpsest of cultural landscapes dating from thousands of years ago with archeological sites through to the 20th century when Anglo settlers tried to make a go of ranching or mining. There were significantly more people on that landscape 100 years ago than they are today. The harsh desert environment pushed most out and ranching destroyed the grasslands. Today, the historic ranching and mining features of the park are managed through a process of documentation and simply allowing it to decay.

Also, in West Texas, TPWD manages several properties that have incredible prehistoric resources, varying from deep deposits in archeological sites within rock shelters to rock art and the natural desert landscapes where water is an all-important resource.

So, these prehistoric landscapes are important to our native American constituents, as we heard just a little bit ago from Holly, is the intersection of that natural world and the human made resources such as those painted images and the archeological sites and the fact that development is minimal at these sites, that they are good examples of a cultural landscape with integrity and significance.

One of these is Hueco Tanks State Historic Site and Park. Hueco Tanks spelled not like W-A-C-O, here, but H-U-E-C-O, the Spanish term for small hole. And it is in those small holes where water was retained after rains, and in this desert landscape for thousands of years, these three mountains peaks that you can see here. That's one, two and there's a third one in the back, and within this area of about 860 acres is Hueco Tanks State Historic Site and Park. Native Americans moved from hunting and gathering to actually sedentary villages here because of the water resources in this location.

The Hueco Bolson in this area is actually very dry. The mountains off in the distance is very dry, so water here was the reason. And because of that landscape, when the visitor is within those mountains, what they see today would have been very much like what the Jornada Mogollon folks, thousands of years ago would have seen.And it is also these cultural resources that the native Americans left behind for us that we are nominating Hueco Tanks as a National Historic Landmark because Hueco has the largest accumulation of painted face masks of anywhere in the Jornada Mogollon region.

Moving from the Big Bend region, just a little bit East into the Lower Pecos, Seminole Canyon is going to be part of a large accumulation of properties that would also be nominated to National Historic Landmark status. TPWD initiated both of the processes with both Hueco Tanks and the Lower Pecos folks because we feel that these landscapes are incredibly important and they retain a lot of integrity. You'll hear a lot about that tomorrow from our colleagues in the National Park Service, who are actually running that process. We started it with a group of stakeholders and other folks in the region and the NPS is going to talk a lot about that tomorrow.

But for us at TPWD, moving from the particularistic to the holistic, we continue to strive and struggle for ways to protect, while at the same time allowing public access for enjoyment of their cultural landscapes. Not all of them are significant, not all of them have integrity, but all of them in one way or another play into Texans and their understanding of themselves and their sense of place.

These resources ran from vernacular ranching features found all over the state to the highly designed landscapes with the CCC era. It is the public that we strive to do this for so they can enjoy and learn from their parks and enjoying that sense of place. Indeed, as social scientists, we realized that the parks landscapes, whether recreational or historical or cognitively created and recreated in the minds of each visitor over time, based on their own backgrounds, experiences, family values and ethnicities.

How we in the CR program handle landscapes on a day to day basis, case by case basis tends to fall to the functional and legal as review and manage for change while maintaining as much integrity of place as we can. We also impart our knowledge and concepts of cultural landscapes to our interpreters who teach the public about their past and encourage stewardship. Though sometimes at the end of the day, the public just want a cool place to sit in the stream and have a soda. We have to deal with that on a particular level. We also have to remember that humans are not the only ones to inhabit these landscapes.

Thank you.

Michael Strutt, Texas Parks and Wildlife

Speaker Biography

Dr. Michael Strutt is the Director of Cultural Resources at Texas Parks and Wildlife after working for many years as an archaeologist and architectural surveyor. His professional experience includes working at historic sites such as Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest and Monticello and George Washington's Mount Vernon. He earned a B.A. in Anthropology from Edinboro University in Pennsylvania, an M.A. in historical archeology from the College of William and Mary, and holds a Ph.D. in historic preservation from Middle Tennessee State University.