Last updated: March 19, 2025

Article

Climate and Water Monitoring at Montezuma Castle National Monument: Water Year 2022

Montezuma Well, Montezuma Castle National Monument.

Overview

Together, climate and hydrology shape ecosystems and the services they provide, particularly in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. Understanding changes in climate, groundwater, and surface water is key to assessing the condition of park natural resources—and often, cultural resources.

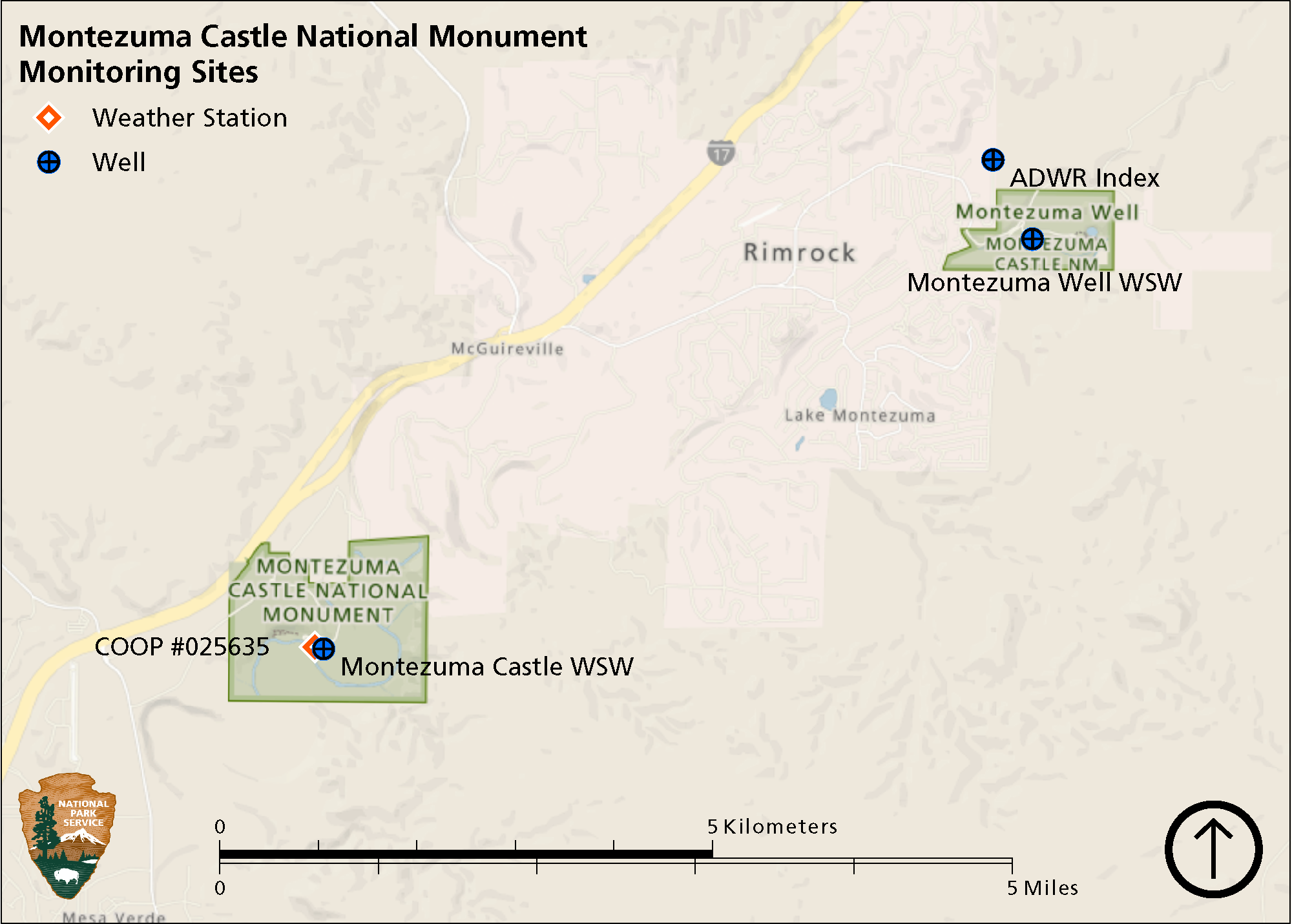

At Montezuma Castle National Monument (NM) (Figure 1), Sonoran Desert Network scientists study how ecosystems may be changing by taking measurements of key resources, or “vital signs,” year after year—much as a doctor keeps track of a patient’s vital signs. This long-term ecological monitoring provides early warning of potential problems, allowing managers to mitigate them before they become worse. At Montezuma Castle NM, we monitor climate, groundwater, and springs, among other vital signs.

Surface-water and groundwater conditions are closely related to climate conditions. Because they are better understood together, we report on climate in conjunction with water resources. Reporting is by water year (WY), which begins in October of the previous calendar year and goes through September of the water year (e.g., WY2022 runs from October 2021 through September 2022).

This article reports on results of climate and water monitoring done at Montezuma Castle NM in water year 2022.

Figure 1. Monitored weather station and groundwater wells at Montezuma Castle National Monument. WSW = water-supply well. ADWR = Arizona Department of Water Resources. COOP = National Weather Service Cooperative Observer station.

Climate and Weather

There is often confusion over the terms, “weather” and “climate.” In short, weather describes instantaneous meteorological conditions (e.g., it’s currently raining or snowing, it’s a hot or frigid day). Climate reflects patterns of weather at a given place over longer periods of time (seasons to years). Climate is the primary driver of ecological processes on earth. Climate and weather information provide context for understanding the status or condition of other park resources.

Methods

Montezuma Castle NM has operated a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Cooperative Observer Program (COOP) weather station (MONTEZUMA CASTLE NM #025635 (see Figure 1) since 1938. This station provides a reliable, long-term climate dataset used for analyses in this climate and water report. Data from this station are accessible through Climate Analyzer.

Results for Water Year 2022

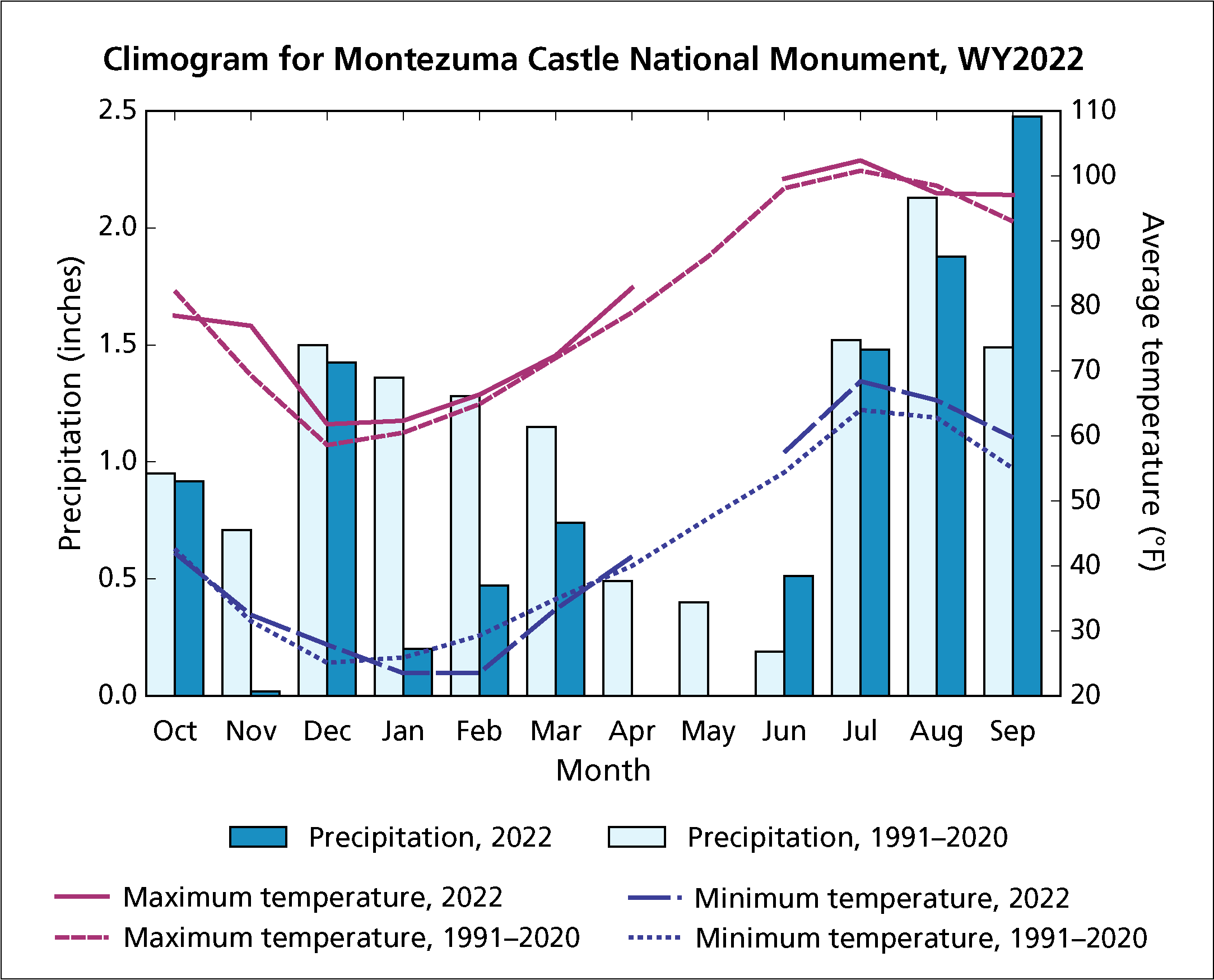

Figure 2. Climogram showing monthly precipitation and mean maximum and minimum temperature, WY2022 and the 1991–2020 means at Montezuma Castle National Monument. Due to missing data, maximum and minimum temperatures are not shown for May. Data source: climateanalyzer.org.

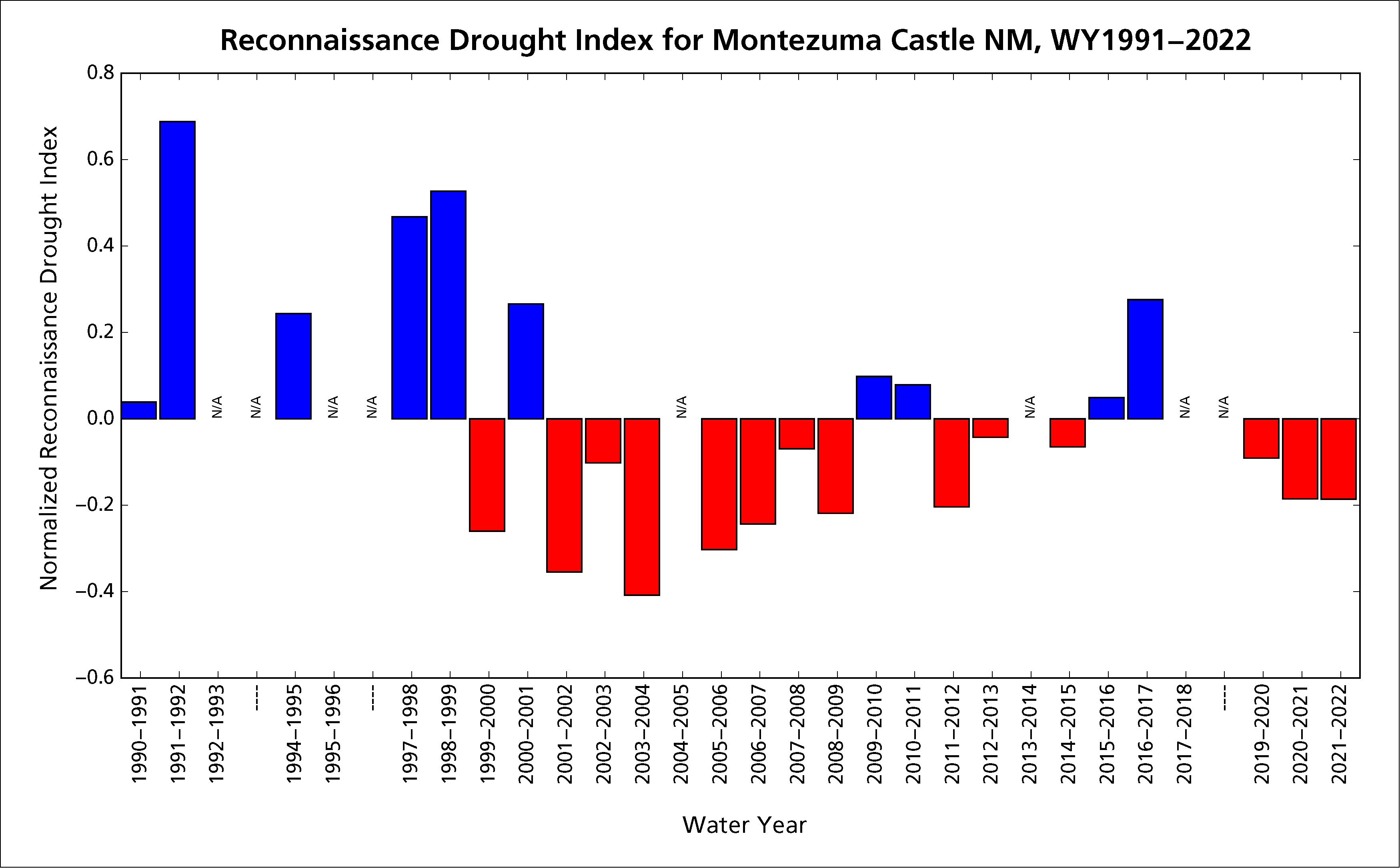

Figure 3. Reconnaissance drought index for Montezuma Castle National Monument, WY1991–2022. Data source: climateanalyzer.org. Drought index calculations are relative to the time period selected (1990–2022). Choosing a different set of start/end points may produce different results.

Precipitation

- Annual precipitation at Montezuma Castle NM in WY2022 was 10.12" (25.7 cm; Figure 2), which was 3.05" (7.8 cm) less than the annual average for 1991–2020.

- Precipitation was near or below monthly averages for most of the year, except in June and September.

- Early monsoon rains in June were 2.5 times the 1991–2020 average.

- September received 66% more rainfall than average.

- No extreme daily rainfall events (>1"; 2.54 cm) occurred in WY2022, compared to the average annual frequency of 1.8 days with extreme rainfall events.

Air temperature

- Mean annual maximum and minimum air temperatures could not be calculated in WY2022, due to missing temperature data on 20 days, primarily during May–July.

- Average monthly maximum temperatures in WY2022 were warmer than the 1991–2020 monthly averages for most of the year, up to 7.6°F (4.2°C) warmer in November.

- Average monthly minimum temperatures were more variable relative to monthly averages for 1991–2010 (Figure 2).

- Extremely hot temperatures (>105°F; 40.6°C) occurred on 17 days in WY2022, slightly fewer than the average annual frequency for 1991–2020 (20.9 days). However, extremely hot temperatures may be underrepresented due to missing data during the warm season.

- Extremely cold temperatures (<22°F; -5.6°C) occurred on 29 days, more than the average annual frequency for 1991–2020 (23.3 days).

Drought

Reconnaissance drought index (Tsakiris and Vangelis 2005) provides a measure of drought severity and extent relative to the long-term climate. It is based on the ratio of average precipitation to average potential evapotranspiration (the amount of water loss that would occur from evaporation and plant transpiration if the water supply was unlimited) over short periods of time (seasons to years). From the perspective of both precipitation and potential evapotranspiration, the reconnaissance drought index for Montezuma Castle NM indicates that WY2022 was drier than the average for 1991–2022 (Figure 3).

Groundwater

Groundwater is one of the most critical natural resources of the American Southwest. It provides drinking water, irrigates crops, and sustains rivers, streams, and springs throughout the region. Groundwater is closely linked to long-term precipitation and surface waters, as ephemeral flows sink below ground to reappear months, years, or even centuries later in the form of perennial and intermittent streams and springs. Groundwater also sustains vegetation and is the primary source of water for almost all humans in the southwestern U.S. Groundwater therefore interacts either directly or indirectly with all key ecosystem features of the arid Sonoran Desert ecoregion.

At Montezuma Castle NM, groundwater is monitored using three wells: the water supply wells for both the Castle and Well units, and a third well (ADWR Index) outside the Well unit (see Figure 1 in the Overview). Each well is monitored annually by the Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR); data are available at Arizona Department of Water Resources Well Registry Search.

Results for Water Year 2022

Groundwater monitoring results for WY2022 are summarized in Table 1.

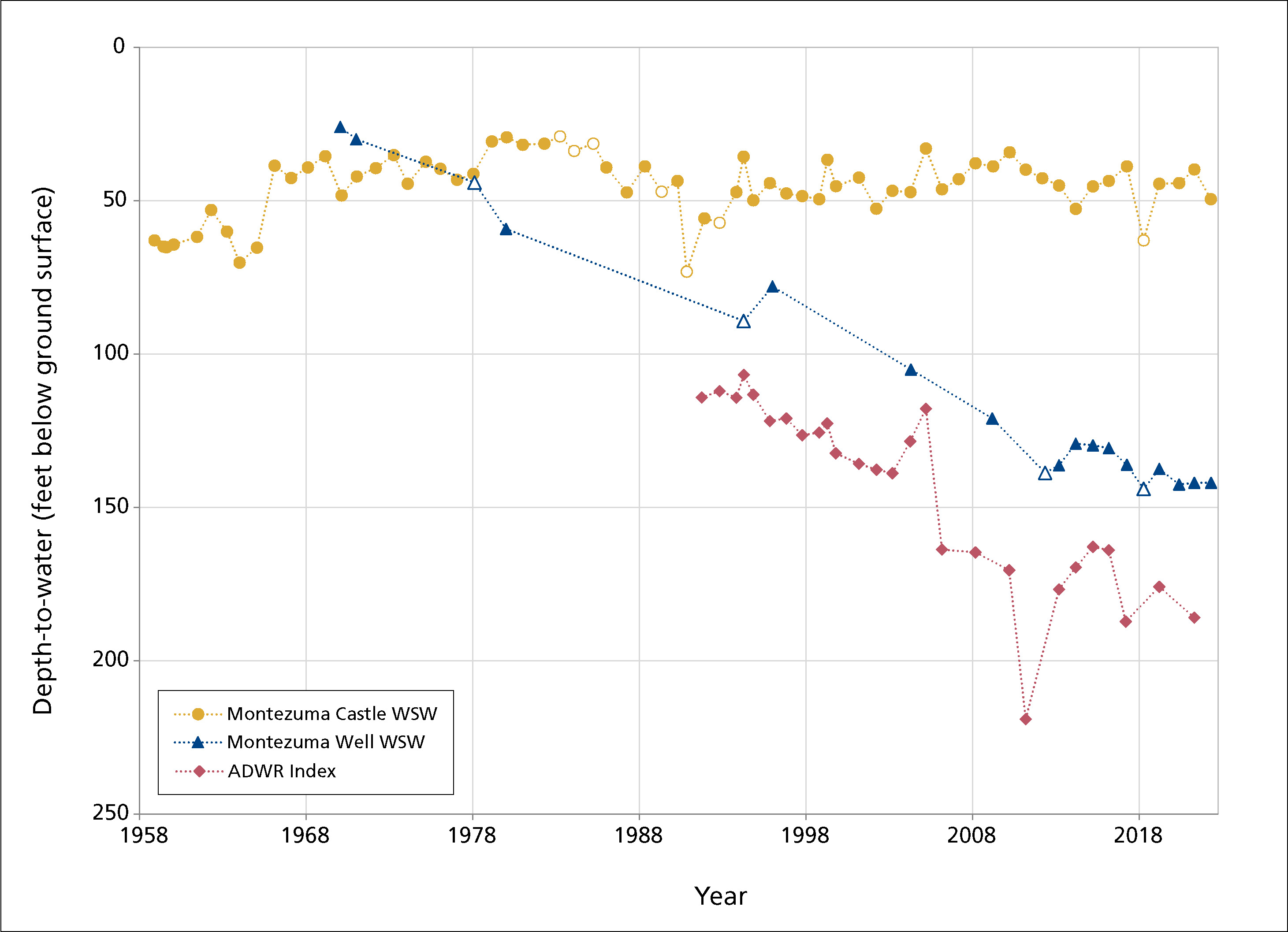

- In WY2022, the Montezuma Castle WSW (water-supply well) water level was 49.50 feet (15.09 m) below ground surface (bgs). This was lower than the previous water year but within the historic range (Figure 4), which has been generally stable since the monitoring well was established in 1958. Water levels in this well are likely regulated by flow in adjacent Beaver Creek.

- The Montezuma Well WSW water level was 142 feet (43.28 m) bgs in WY2022, the same as in WY2021. While water levels in Montezuma Well WSW have been stable over the last three years, the entire monitoring record demonstrates a steady decline.

- The ADWR (Arizona Department of Water Resources) Index well was not measured in WY2022, but the monitoring record also demonstrates a steady decline similar to that of the Montezuma Well WSW.

Table 1. Groundwater monitoring results in water year 2022, Montezuma Castle National Monument.

| Name1 | State well number | Wellhead elevation (feet amsl)2 | Depth-to-water (feet bgs)3 | Water-level elevation (amsl feet) | Elevation change from water year 2021 (± feet) | Elevation change from earliest recorded water level (± feet) (water year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montezuma Castle WSW | 629124 | 3,190 | 49.50 | 3,140.50 | -9.70 | 15.86 (1959) |

| Montezuma Well WSW | 629125 | 3,515 | 142.00 | 3,373.00 | 0.00 | -97.90 (1970) |

| ADWR Index | 514006 | 3,580 | Not collected | – | – | – |

1WSW = water-supply well; ADWR = Arizona Department of Water Resources

1amsl = above mean sea level

2bgs = below ground surface

Figure 4. Depth-to-water (feet below ground surface) at three groundwater monitoring wells at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 1958–2022. White data points indicate that the measurement was made when the well was being pumped or had recently been pumped.

Figure 4. Depth-to-water (feet below ground surface) at three groundwater monitoring wells at Montezuma Castle National Monument, 1958–2022. White data points indicate that the measurement was made when the well was being pumped or had recently been pumped.

Springs

Background

Springs, seeps, and tinajas (small pools in a rock basin or impoundments in bedrock) are small, relatively rare biodiversity hotspots in arid lands. They are the primary connection between groundwater and surface water and are important water sources for plants and animals. For springs, the most important questions we ask are about persistence (How long was there water in the spring?) and water quantity (How much water was in the spring?).

Sonoran Desert Network springs monitoring is organized into four modules, described below. Results are reported in metric measurements.

Site characterization

This module, which includes recording GPS locations and drawing a site diagram, provides context for interpreting change in the other modules. We also describe the spring type (e.g., helocrene, limnocrene, rheocrene, or tinaja) and its associated vegetation. Helocrene springs emerge as low-gradient wetlands. Limnocrene springs emerge as pools, and rheocrene springs emerge as flowing streams. This module is completed once every five years or after significant events.

Site condition

We estimate natural and anthropogenic disturbances and the level of stress on vegetation and soils on a scale of 1–4, where 1 = undisturbed, 2 = slightly disturbed, 3 = moderately disturbed, and 4 = highly disturbed. Types of natural disturbances can include flooding, drying, fire, wildlife impacts, windthrow of trees and shrubs, beaver activity, and insect infestations. Anthropogenic disturbances can include roads and off-highway vehicle trails, hiking trails, livestock and feral-animal impacts, removal of invasive non-native plants, flow modification, and evidence of human use. We take repeat photographs showing the spring and its landscape context. We note the presence of certain obligate wetland plants (plants that almost always occur only in wetlands), facultative wetland plants (plants that usually occur in wetlands, but also occur in other habitats), and non-native bullfrogs and crayfish, and we record the density of invasive, non-native plants.

Special project: eDNA inventory. In WY2022, SODN implemented an inventory of rare and invasive species and pathogens in perennial springs using environmental DNA (eDNA) techniques. Samples were preserved in ethanol prior to DNA extraction and analysis by the Goldberg Lab at Washington State University. The following rare and invasive species and pathogens were targeted:

- The non-native, invasive American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), which has been observed within the monument along Beaver and Wet Beaver creeks (Schmidt et al. 2006).

- The pathogen, chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), a major threat to amphibians globally that is currently expanding in the American Southwest, but has not been previously detected in Montezuma Castle National Monument.

- Ranaviruses that can infect amphibians and produce 90–100% mortality in tadpoles and adults and can persist in affected wetlands. Ranaviruses have not been previously detected at Montezuma Castle National Monument.

- The native amphibian, Chiricahua leopard frog (Rana chiricahuensis), a federally designated threatened species whose historic and current known range and critical habitat are south of Montezuma Castle National Monument (Schmidt et al. 2006).

- The native amphibian, lowland leopard frog (Rana yavapaiensis), a species of conservation concern that has been historically found within the monument (Schmidt et al. 2006) but may be locally extirpated.

- The native aquatic snake, northern Mexican garter snake (Thamnophis eques megalops), a federally designated threatened species which has been historically found within the monument (Schmidt et al. 2006) and may still occur within its boundaries in suitable wetland habitats. Designated critical habitat includes the nearby Verde River.

- The native mammal, jaguar (Panthera onca), a federally designated endangered species that was historically found within Montezuma Castle National Monument, although current designated critical habitat for jaguar recovery is located well south of the Verde Valley.

Water quantity

We measure the persistence of surface water, amount of spring discharge, and wetted extent. To estimate persistence, we analyze the variance of temperature measurements taken by logging thermometers placed at or near the orifice (spring opening). Because water mediates variation in diurnal temperatures, data from a submerged sensor will show less daily variation than data from an exposed, open-air sensor; this tells us when the spring was wet or dry. Surface discharge is measured with a timed sample of water volume. Wetted extent is a systematic measurement of the physical length (up to 100 m), width, and depth of surface water. It is assessed using a technique for either standing water (e.g., limnocrene and helocrene springs) or flowing water (e.g., rheocrene springs).

Water quality

We measure core water-quality parameters and water chemistry. Core parameters include water temperature, pH, specific conductivity (a measure of dissolved compounds and contaminants), dissolved oxygen (how much oxygen is present in the water), and total dissolved solids (an indicator of potentially undesirable compounds). Discrete samples of these parameters are collected with a multiparameter meter. If the meter failed calibration check(s), we do not present data. Water chemistry is assessed by collecting surface water sample(s) and estimating the concentration of major ions with a photometer in the field. These parameters are collected at one or more sampling locations within a spring. Data are presented only for the primary sampling location. Each perennial spring is somewhat unique, and there are not water-quality standards specific to most perennial springs in Arizona. Where conditions exceed water-quality standards for other surface waters (rivers, streams, lakes, and reservoirs), we note it, but the reader is advised that these standards were not developed for perennial springs. Our ongoing data collection at each spring will improve our understanding of the natural range in water-quality and water-chemistry parameters for a given site.

Results for Water Year 2022

Expansion Spring

Figure 5. Expansion Spring emerges from a limestone outcrop at Montezuma Castle National Monument, March 2022. NPS photo.

Expansion Spring (Figure 5) is a small rheocrene spring (emerges as a flowing stream) that surfaces from the base of a limestone outcrop in a side canyon and flows into Beaver Creek. When characterized on March 21, 2022, Expansion Spring contained cool, clear water flowing rapidly down a narrow (30–75 cm) channel (~10 m, fall of 1.5 m) to a large, shallow pool (3 × 2 m) located about a meter above the river (Figure 6). This pool was dammed by a large pile of boulders and cobbles, and overflowed into the creek in several locations. There were scattered patches of algae in the mixed cobble and muck bottom of the channel and pool. No aquatic animals were observed within the springbrook. The site is well-shaded by cottonwood trees.

Figure 6. Expansion Spring feeds a shallow pool adjacent to Beaver Creek. NPS photo.

Site condition. In WY2022, the crew recorded slight disturbance from wildlife use, as deer and raccoon tracks were noted in and around the lower pool. Disturbance from wildlife use has varied since monitoring began in WY2021. There were no other anthropogenic or natural disturbances observed at Expansion Spring in WY2022.

The crew did not observe crayfish or bullfrogs (non-native invasive aquatic animals), nor did they detect any non-native plants. No obligate or facultative wetland plants were observed, though the nearby Beaver Creek riparian corridor contained a number of wetland plant species.

Special project: eDNA inventory. Four water samples were collected and filtered (0.45-µm mesh) from the orifice, springbrook, and terminal pool at Expansion Spring on March 21, 2022. None of our target organisms (see Methods section) was detected. Additional data collection for this inventory is occurring at this site, with additional information provided in a future, more detailed report.

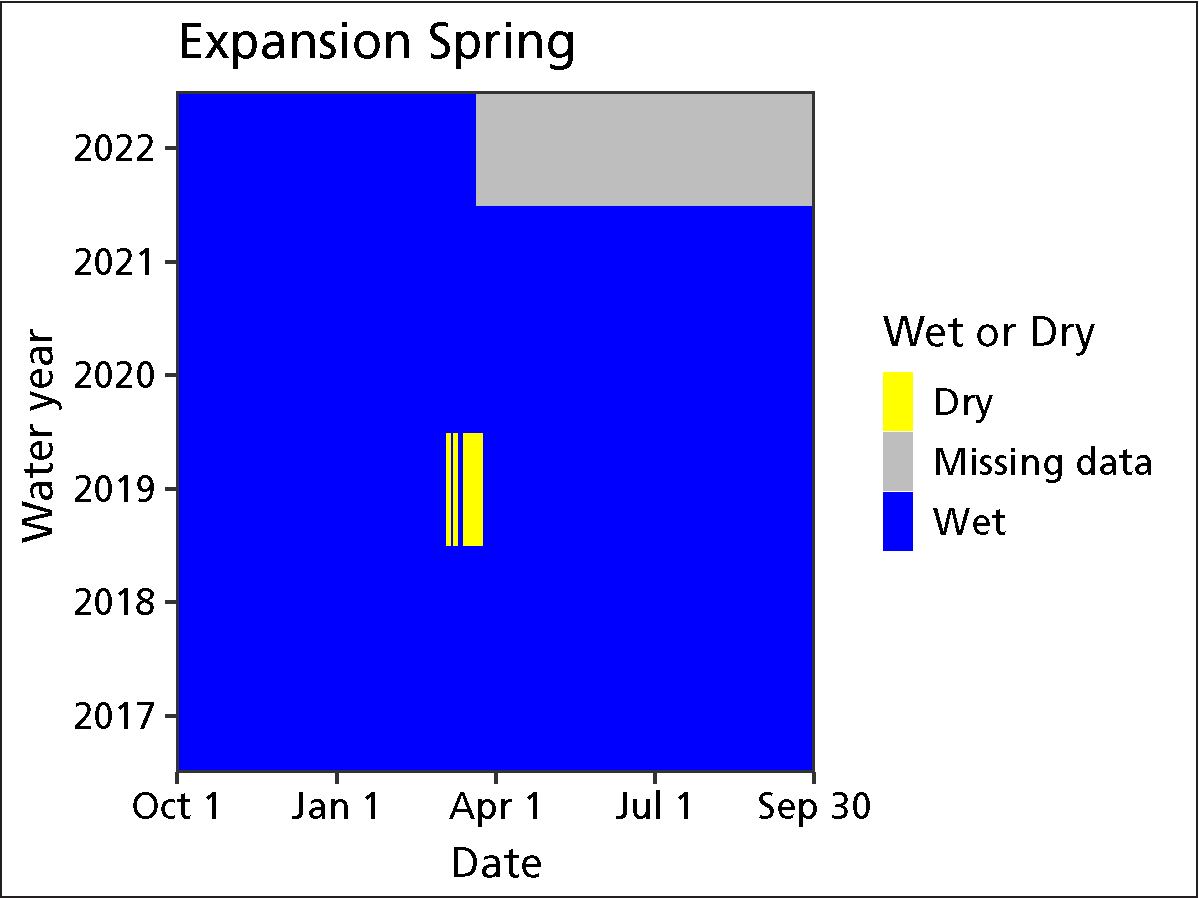

Figure 7. Water persistence in Expansion Spring, Montezuma Castle National Monument, 2017–2022.

Water quantity. During the WY2022 visit on March 21, 2022, the spring was wetted (contained water). Discharge was estimated at 151.1 ± 6.1 liters per minute. Due to changes in sampling locations, discharge from previous years is not comparable to that of WY2022. Wetted extent was evaluated using a method for flowing water. The total brook length was 19 meters. Width and depth averaged 58.2 centimeters and 4.9 centimeters, respectively. Wetted extent was within the range observed in past years (Table 1).

Temperature sensors indicated that Expansion Spring was wetted for 172 of 172 days (100%) measured up to the WY2022 visit (Figure 7). In prior water years, the spring was wetted 95.3–100% of the days measured.

Water quality. Core water-quality and water-chemistry data were collected at the primary sampling location. The values were generally within the range recorded in prior years (Tables 2 and 3), although potassium (K) and sulfate (SO4) were substantially higher than in previous years (Table 3). Chloride was also slightly higher and pH slightly lower than during the range of prior years.

Table 1. Average (± SD) width and depth (cm) of Expansion Spring within springbrook length (up to 100 m) in WY2022, and a range of values from prior years.

| Measurement | WY2022 value (range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|

| Width (cm) | 58.2 ± 47.9 (21.3–62.8) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| Depth (cm) | 4.9 ± 3.6 (0.3–12.8) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| Length (m) | 18.9 (11.5–21.6) | 2017–2021 (4) |

Table 2. Data on core water-quality parameters for Expansion Spring in WY 2022, and a range of values from prior years.

| Sampling location | Measurement location (width, depth) |

Parameter | WY2022 value (range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Center | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) | 7.58 (0.85–7.75) | 2017–2021 (3) |

| 001 | Center | pH | 7.23 (7.3–7.49) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Specific conductivity (µS/cm) | 596 (580.9–883) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Temperature (°C) | 16.2 (15.5–20) | 2017–2021 (5) |

| 001 | Center | Total dissolved solids (mg/L) | 388 (377.6–572) | 2017–2021 (4) |

Table 3. Data on water-chemistry parameters (mg/L) for Expansion Spring in WY2022, and a range of values from prior years.

| Sampling location | Measurement location (width, depth) |

Parameter | WY2022 value (range of prior values) |

Prior years measured (# of measurements) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | Center | Alkalinity (CaCO3) | 310 (265–350) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Calcium (Ca) | 54 (50–66) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Chloride (Cl) | 32 (14–29) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Magnesium (Mg) | 24 (33–70) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Potassium (K) | 35 (3.1–3.4) | 2017–2021 (4) |

| 001 | Center | Sulphate (SO4) | 8 (0–2) | 2017–2021 (4) |

Report Citation

Authors: Kara Raymond, Andy Hubbard, Cheryl McIntyre

Raymond, K., A. Hubbard, and C. McIntyre. 2023. Climate and Water Monitoring at Montezuma Castle National Monument: Water Year 2022. Sonoran Desert Network, National Park Service, Tucson, Arizona.

Tags

- montezuma castle national monument

- climate

- groundwater

- springs

- monitoring

- weather

- arizona

- weather and climate

- sodn

- science

- american southwest

- science and resource management

- swscience

- water

- water in the desert

- water in the west

- water quality

- water quality monitoring

- sonoran desert

- sonoran desert network

- monitoring report