Last updated: July 8, 2022

Article

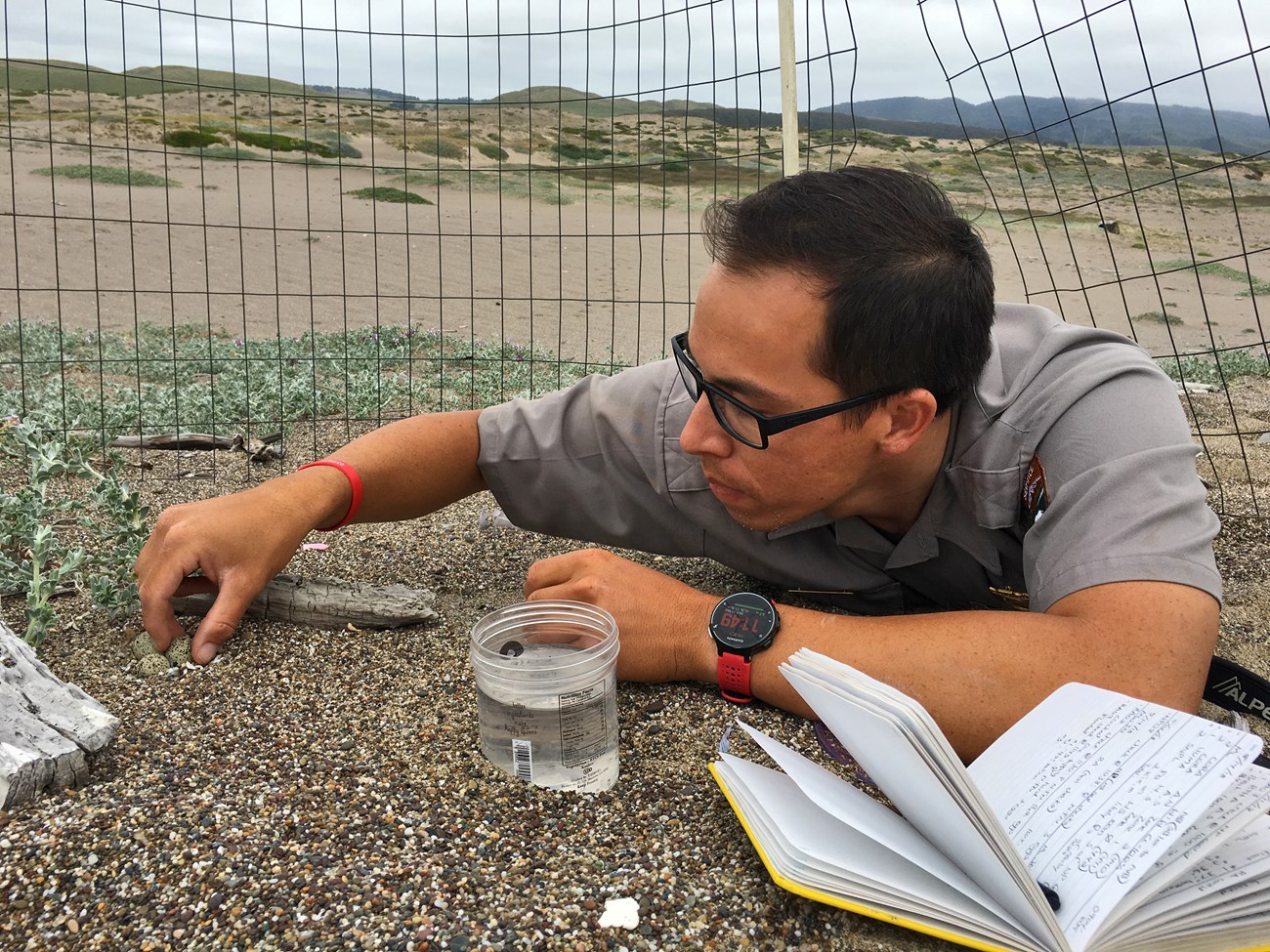

Scientist Profile: Matt Lau, Wildlife Biologist

Photo courtesy of David Pascoe

Connecting with the Natural World

“I actually grew up near Point Reyes [National Seashore], in Petaluma, CA. When I was a kid we’d go camping at a nearby park, Samuel P Taylor State Park, and that exposed me to a lot of that kind of environment and habitat and redwoods. I always remember just being around Stellar's jays so much at Samuel P Taylor and that really helped connect me with birds and the natural world. I just loved their boisterous personality so much ‘cause in a lot of ways it was very opposite of who I am myself.”

“I was also fortunate that my dad loved to bring me to national parks when I was younger. He immigrated from Hong Kong when he was young and was so enamored with the American outdoors and the national park system. We visited many of our national parks multiple times: Yosemite, Redwoods, Lassen, Crater Lake, Yellowstone, and Grand Tetons. I spent a lot of time in my formative years being surrounded by nature and wildlife.”

“And then in high school I joined the United Anglers of Casa Grande, which really formed the base of my career and getting into conservation. So I actually started out with working with fish and then converted over to birds when I went into college at Humboldt State University. Once I got into grad school I got into snowy plovers and did research on ravens in plover habitat. That's kinda how I got connected to Point Reyes and the plover monitoring program there, near where I grew up.”

A Diversity of Ideas

“As a young, aspiring conservation biologist, I didn't really have any inspirational professionals that looked like me. The conservationists that I looked up to, like Crocodile Hunter Steve Irwin, Jeff Corwin, and my early supervisors, were mostly white men. The conservation field has historically been white-dominated. But conservation issues aren't just white issues—they affect everyone. Which means we need a diversity of ideas and backgrounds to help solve these issues. Because of this, it's important to me to increase the diversity of people in the conservation workforce, particularly with people from underrepresented communities and communities directly affected by environmental issues. I want kids to see themselves represented in a National Park Service uniform, or as a biologist working with an endangered species, and see that it's possible they can do the same.”

Type-2 Fun

“Being a wildlife biologist is pretty awesome, I have to say. To me, it's the dream job. It's definitely very hard work, labor-wise. I mean I'm walking long distances on the beach almost every day between March until September, during the plover season. It's like type-2 fun where it's difficult in the moment but afterwards, it's very rewarding. Especially after, say, attending a nest hatch and banding chicks and devoting several days to monitoring the chicks and seeing them grow up and fledge. And the following year, seeing them as adults and breeding, which is happening a lot this year. Then there's the required portion of office work which in some ways can be fun, but I’d much rather be working outside.”

Photo courtesy Joey Negreann / Point Reyes National Seashore Association

“We essentially monitor breeding success of snowy plovers. And that is nest success and then also chick survival as well as another productivity measure called the number of chicks fledged per male. On top of that, we're also trying to boost reproductive success. To increase nest success, we use nest exclosures [to keep predators out]. And we use symbolic fencing to help give plovers some space from the visiting public and dogs to reduce disturbance. “

“Predation is a huge issue affecting the plover population in Point Reyes. Namely common ravens. They're the number one nest predator, and likely hatchling predator as well, although there's a little bit less evidence for that. I'm actually putting out a peer reviewed article comparing nest success and raven activity and there’s a definite statistical relationship. Nests don't do very well when raven activity is higher.”

“I really love being curious and finding new things and collaborating with other scientists. And producing peer reviewed work, spreading that knowledge, and sharing science with other people.”

NPS / Marjorie Cox, NMFS Permit No. 21425

Beach Muffins

“Even now, every time I see snowy plovers, I'm astounded by how I was able to find them. They just camouflage so well, it's amazing how well they can hide. Seeing one for the first time I think I was surprised by how small they are. And also how adorable they are. I've heard nicknames of snowy plovers like ‘beach muffins’ and ‘beach snicker doodles’—very cute nicknames.”

“It's not obvious how much personality they have at first. But over the past few years, I've noticed different personalities between birds, especially females on nests. For example there is a female on a nest in the [Abbotts Lagoon] restoration area right now, who has exhibited very weird and unusual behavior when we’re checking the eggs at her nest site. Usually, females are at least 10 to 15 meters away, watching from afar and sometimes vocalizing or doing like broken-wing displays. But this female will not leave her nest. She'll stay within a few feet from you as you're picking up and checking the eggs for hatch. Sometimes when we have an egg in hand and we're checking it for any cracks, she's just back on the nest, incubating the other two eggs just a foot away from you.”

NPS / Matt Lau

Photo courtesy Gina Graziano

Everyone has an Impact

“One thing I really enjoy about my job is that I get to talk to visitors about snowy plovers and conservation in general. Being able to connect people with science is something that I really enjoy. Sharing my love for science and conservation is something that I look forward to every day. I like to emphasize that everyone has an impact wherever you go. Even the smallest impact can have cascading effects. Like leaving orange peels on the beach. Which you would think is fine because it's compostable, but that bright orange thing might attract a raven to that spot. And there just might be a snowy plover nesting 100 meters away, and that raven can then find the snowy plover nest. And you may have indirectly affected a threatened species. So every little thing that you do can have some sort of impact on something else.”

Not Walking on the Beach

“Short vacations kind of scattered here and there throughout the summer are definitely essential for my wellbeing. I like camping—anything outdoors. I will go camping on the coast occasionally, but generally won't be walking on the beach, because I can get sick of walking on the beach. I like visiting other national parks. Hiking. Birding. Just anything in to keep active. Or anything that will be relaxing and gives me some time off my feet. Massages are good, too!”

People are More Aware

“Sometimes I feel like there's an insurmountable number of environmental problems that are hard to overcome. I worry that there's some new thing that's gonna affect snowy plover populations or any other sensitive species. Like ravens, and now climate change and sea level rise. I often have to remind myself that these species are resilient, and they've been around for millions of years, so they'll fight and persist with our help. What gives me hope is that people are much more aware of environmental issues and challenges that species are facing. And happy to help with conservation, including younger generations. I think that's what really keeps me going.”

Profile adapted from an interview by Jessica Weinberg McClosky, May 2022

Further Reading

- Lau, M. 2022. Western Snowy Plovers Could Face Multiple Threats from Climate Change. Park Science 36(1). Published online 22 June 2022.

- San Francisco Bay Area Network:

- Pacific Coast Science & Learning Center:

- Snowy Plovers at Point Reyes