Last updated: August 3, 2023

Article

Salsa Is More Than Salsa

How do human interactions and musical categories shape history?

The New York Public Library

Different types of salsa music have existed across the years, like salsa romantica, salsa dura, salsa consciente, and salsa caliente, to name a few. There are also many types of music that make up salsa history, such as son, bomba, plena, bugalú, mambo, and more. Salsa dancing has many variations too, with different styles developed in New York, Cuba, Colombia, Los Angeles, and beyond.

These lists and details go on and on. Depending on the traditions, values, and experiences that people have, they might understand salsa to mean different things. Some people we might call salseros or sonatas wouldn’t even use the term “salsa” themselves. Tito Puente famously said "Yo sólo conozco una Salsa que venden en botella, llamada catsup. Yo toco música Cubana.” (I only know a Salsa sold in a bottle called ketchup. What I play is Cuban music.)

Even though Tito Puente called his music Cuban, others might call it mambo, salsa, or even Puerto Rican music. There are many debates and opinions about what makes salsa… salsa. Salsa is more than salsa: salsa is all of the connections and perspectives that bring people together to dance, sing, celebrate, and protest under the umbrella of salsa. Salsa is a complex mix of genres, cultures, and global interactions. To understand how salsa is more than salsa, read about these many variations of salsa, the commercial development of salsa in New York City, and a timeline of salsa through the decades.

Salsa Is Everything, Everywhere, All At Once

Genre

Categories help us understand the world. In music, genres are categories for certain musical, cultural, or social aspects that belong together. Genres can be defined through many aspects, however: geography, context, technique, style, and form can all be a part of identifying a genre. Genres are sometimes difficult to understand since people may not agree on what factors make up a genre. Salsa music is a genre that many people understand according to their own experiences, since the genres that created salsa also continued to exist and transform in their own ways.

For example, mambo is a genre of music, and so is salsa. Yet, many of their styles, traditions, or experiences are similar. These similarities lead many people to use mambo and salsa interchangeably. Others with different perspectives are specific in using the terms separately. Musical genres affect existing genres and create new genres, sometimes through combining and mixing throughout history. The genre of salsa arose through many genres from different cultures that came to connect, transform, and resist over the years.

Transculturation

People from different cultures come into contact with one another for many reasons, largely through migration. When these cultures interact, they often create new forms that are blends or transformations of many beliefs or practices. These can be seen in religion, art, language, and social customs. Transculturation is a part of the history of salsa. For example, musical cultures of enslaved Africans and their descendants interacted with European musical cultures throughout the Western hemisphere to create new forms of music. Transculturation is also a part of the story of the Latino communities in the United States. This is an important concept that helps us understand how salsa is from the intersections of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the United States, and beyond. Salsa grows out of a mix of transcultural interactions over generations of global contact.

Globalization

The world has become an increasingly interconnected place. As people sought opportunities for trade, they traveled around the world for goods, money, and culture. Developments in technology, such as transportation and financial institutions, made it easier for people to move and interact. Colonization and imperialism were major contributors to globalization. The economy of slavery, for example, was significant in connecting the Americas, Africa, and Europe. Even settled countries that eventually became independent were still dependent on dominant powers, meaning that global connections were here to stay.

People and nations have continued to exchange ideas, culture, and money. Salsa spread between the Caribbean and the United States to Latin America and to other corners of the globe as advances in technology and increasing migration made global connections easier, faster, and more consistent. In New York City, the popularity of Latin music and salsa were commercialized, helping it spread.

Commercializing Latin Music and Salsa

Salsa’s popularity and use as an umbrella term is largely due to the commercialization of Latin music. Before the creation of recording technology and wireless communication, it was harder for musical genres from around the world to come into contact with one another. People had to be physically together and create music live to share their own sounds. Inventions like the phonograph in 1877 and the radio in 1895 changed how the world engaged with sound. Explore some of Thomas Edison’s early sound recordings here.

In Cuba and Puerto Rico, phonograph companies recorded their first records in 1918 and radio stations broadcasted their first operations in 1922. Records and radio helped Caribbean music develop into salsa. Mass media made music more accessible to more people. This meant that musicians in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and New York City could exchange musical genres and styles with more ease. Yet, companies needed to make money off of these records. As a result, the music that appealed to consumer audiences became the music that people invested in. The popularity of music came to be defined through the music that sold the most records, concert tickets, or radio slots.

In New York City, Tin Pan Alley was a significant location for commercializing music. Located in Manhattan, five buildings on Tin Pan Alley were designated as New York Individual Landmarks in 2019. Tin Pan Alley’s business practices in the first half of the 20th century set the stage for popular music, copyright laws, and publishing norms in the United States. Record labels had to create reputations to attract talent that would sell. For Latin musicians, record labels like Riverside, Alegre, Tico, and RCA were responsible for representing their music on the commercial market.

The salsa boom of the 1970s was substantially influenced by the development of Fania Records. Fania was co-founded by Gerald “Jerry” Masucci and Johnny Pacheco in 1964 as a new record label that sought to treat its artists like a family. As Fania grew, it bought several independent Latin music labels like Alegre and Tico and expanded its markets beyond New York City. Fania eventually came to own a near-monopoly over Latin music.

Fania put together the Fania All-Stars, a group of top Latin musicians, who became widely popular after performing at the Cheetah club in 1971. Fania released Our Latin Thing in 1972, a film based on the previous year’s performance. Our Latin Thing conveyed a narrative that spoke to New York’s migrant Puerto Rican community and emphasized an urban Latino identity. The boom in popularity of salsa following Our Latin Thing led Fania to establish a marketing formula for salsa that depended on a recognizable image of star quality, Puerto Rican culture, and Latino community.

Fania Records played a large role in creating, circulating, and dominating salsa. The story of Fania shows how the economic factors of the music industry shaped salsa. Since music had to sell, salsa had to sell. Part of the reason salsa speaks to so many Latino people is that it was made to appeal to a community of people who enjoyed Latin music in New York, across the United States, and throughout Latin America. In this way, salsa is also an industry label that emerged out of the commercial need to manage music in a world with changing communities looking for connection.

A Brief Timeline of Salsa

Dive into the decades of salsa!

Enslaved Africans preserved and transformed their musical traditions in cabildos and barracones in Puerto Rico and Cuba. This led to the creation of new instruments such as the bongo, and new rhythms like yuka and makuta

In Cuba, fraternal societies called Abakuá formed. These societies’ masculine drum traditions formed a stylistic basis for rumba.

In Cuba, the musical practice of rumba was developed among dock-working Afro Cubans in Matanza. Rumba includes the musical forms of columbia, yambú, and guaguancó. The essential instruments claves and tumbadoras/congas were also created by these dock workers. At the same time, Miguel Faílde developed danzón, which became Cuba’s official dance song. Charangas featuring piano, timbales, güiro, flutes, and strings became the influential ensembles that played danzón.

As Cuba sought to define its culture, the use of drums of African origin were banned in Havana. Meanwhile, genres in Cuba’s Oriente Province including nengón, kirbiá, changüí, tumba, and punto guajiro mixed to create the son, emphasizing the tres (with its guajeo rhythm) and bongo as instruments. The plena—a now-traditional genre of music using tambourines—was born in the towns of the southern coast of Puerto Rico.

Son spread across Cuba. The first son recordings, including "Amalia Batista" and "La otra cara, Mi nena," were played by the group "Sexteto Habanero Godínez" in Hotel Inglaterra. The Cuban government continued to suppress practices derived from Africa. Jazz musicians from the United States began performing in Cuba while the people of Harlem were influenced by the tango. In Puerto Rico, plena ensembles began to emerge in the Ponce area. Puerto Rican music including aguinaldos and danzas were recorded for the first time. Puerto Ricans including Rafael and Jesús Hernández joined the US 369th Infantry "Harlem Hellfighters" band, performing jazz and settling in New York.

In Cuba, son surpassed danzón as the island’s most popular music, entering its golden age. The government continued suppressing African-derived practices, especially congas and bongos. Arsenio Rodríguez formed his first ensemble in Havana. Aniceto Díaz created danzonete out of danzón to compete with son, continuing the popularity of charangas. The National Prohibition Act in the United States drove drinking overseas to Cuba and Puerto Rico. Increased tourism and the introduction of radio in Havana spread son internationally. Radio also drew more attention to Puerto Rican musicians. Bachata is recorded for the first time in the Dominican Republic. The movement of Afrocubanismo began. The Harlem Riots began, continuing to bring together Puerto Ricans in New York City. Soon after, Victoria Hernández opened the first Puerto Rican-owned music store in the city, now known as Casa Amadeo.

Radio continues to spread the Cuban son, while also bringing in jazz, blues, samba, and tango to the island. The all-women ensemble Anacaona forms, Mario Bauzá leaves for the US to become a premier New York trumpeter, and the danzón is transformed yet again, now into mambo. Miguelito Valdés begins the improvisational soneo singing style, arrangers begin to feature piano solos in songs, and Afro Cuban instruments are incorporated into orchestras. In the US, the success of boleros and rumbas lead to a taste for Cuban music. New York City features the first Latin big bands through Augusto Coen y sus Boricuas, and Coen and Alberto Socarrás perform a packed landmark concert at the Park Palace Ballroom. Arsenio Rodríguez records one of his first political songs. Septeto Nacional debuts Ignacio Piñeiro's “Échale salsita,” the first use of the word salsa in Latin dance music.

In Cuba, Arsenio Rodríguez integrated tumbadora into his son groups and created the son montuno sound that significantly influenced salsa. Radios broadcasted batá drums and gained greater international reach. A tuning system for conga and bongo emerged, which allowed Carlos Valdés to popularize the use of two congas. A standard percussion lineup for Latin music then developed in New York through Machito and His Afro Cubans: a combination of bongo, congas, and timbales. Mambo became a widely-used term for Latin music in the city.

Arsenio Rodriguez moved to New York City. The Palladium Ballroom became the center for Latin dance music. Alegre Records was founded. Pérez Prado, Benny Moré, Tito Puente, Tito Rodríguez, Joe Loco, and others popularized mambo in the United States. Carnegie Hall hosted Mambo USA, a landmark big-band concert that kicked off a national mambo tour. In Cuba, Cachao López recorded various descargas: informal sessions of top musicians. These included solos in a montuno format, directly preceding salsa. Rafael Cortijo incorporated Afro Puerto Rican bomba and plena into son montuno with his ensemble, Cortijo y su Combo. Cha cha cha, a triple step dance, emerges in Cuba to accompany mambo, danzon, and danzonete.

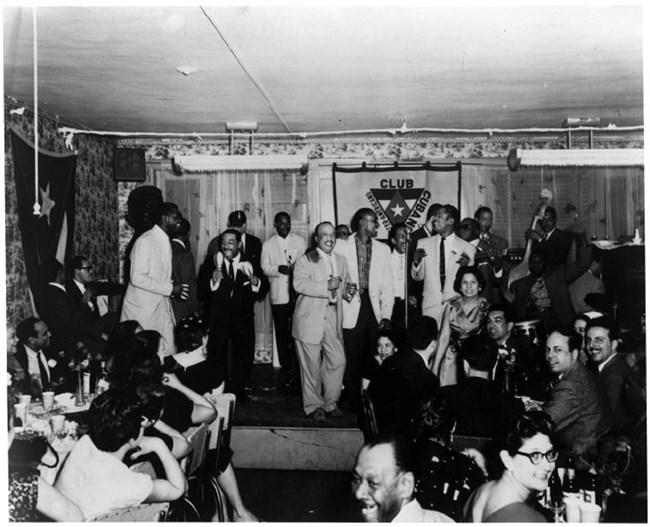

Celia Cruz, like many musicians leaving Cuba, moved to the United States. Arsenio Rodríguez performed throughout Los Angeles before returning to New York. Rodríguez inspired Johnny Pacheco and Ray Barretto, who popularized pachanga after the mambo craze faded, influencing young Puerto Ricans in the city. Pacheco founded Fania Records, becoming its creative director and producer, and put together the Fania All Stars. Bugalú, a genre that mixes son and various African American genres, became popular through Mongo Santamaría, Joe Cuba, and Pete Rodríguez. Tito Puente, Willie Colón, and Hector Lavoe release the first songs and albums to capture the sound of salsa. The clubs at Caborrojeño and Bronx Casino became regular sites for all these artists and more, including Richie Ray, Daniel Santos, Larry Harlow, and Eddie Palmieri.

Salsa was at its most popular. Willie Colón incorporated bomba and samba in some of Fania’s best-selling albums. Fania acquired many other Latin record companies in New York. Rubén Blades collaborated with many musicians, including Colón, Ismael Miranda, and Pete Rodríguez, bringing political and narrative content to salsa that resonated with Latinos in the city. The Fania All-Stars performed their landmark concert at the Cheetah in Manhattan, and the film Our Latin Thing (Nuestra cosa latina) that documented it was influential in establishing salsa. Salsa began to spread beyond New York City, throughout both the United States and the globe. Oscar D’Leon rose to prominence as a singer in Venezuela, and performed many concerts in New York with his group, La Dimensión Latina.

Salsa from around the world was performed in New York, including from Venezuela, Colombia, and Japan. Salsa in Venezuela had been outselling salsa in New York before Colombia became the major center for salsa. There, in Cali, Grupo Niche developed a salsa sound that honored Afro Colombian music. The Japanese group Orquesta de la Luz performed salsa that experimented with the East-West cultural exchange. Salsa romantica began to flourish in Puerto Rico.

The globalization of salsa continued. Salsa became a popular music recognized internationally. Salsa became mixed with pop styles through artists like Gloria Estefan, La India, and Marc Antony. In Cuba, a genre called timba becomes popular. To make timba, charangas mixed salsa, son, and other genres while emphasizing a bass drum sound. The salsa congress, a dance festival focused on salsa, began with the Puerto Rico Salsa Congress and the West Coast Salsa Congress in Los Angeles.

The Grammy Award for Best Salsa Album was awarded four times by the United States Recording Academy to Celia Cruz, Roberto Blades, Tito Puente and Eddie Palmieri, and Los Van Van. The Latin Grammys, a different set of awards presented by the Latin Recording Academy, was founded in 2000 and continues to award the Latin Grammy Award for Best Salsa Album. Salsa congresses began to be held throughout Europe.

Timba bands recorded hybrid albums that mix salsa with genres including reggaeton and hip hop. Several world salsa dancing competitions are held for the first time throughout the globe, including locations around the United States such as Las Vegas, San Diego, Miami, and Atlanta.

As salsa continues to develop, musicians, producers, DJs, and composers revisit or transform salsa in their own ways. Salsa is celebrated through diverse media forms. Many organizations and people work together to preserve and share the histories and legacies of salsa over the years. Communities around the world continue to enjoy salsa.

This article was researched and written by Hermán Luis Chávez, NCPE Intern, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Arroyo, J. “Transculturation, Syncretism, and Hybridity.” In Critical Terms in Caribbean and Latin American Thought: New Directions in Latino American Cultures, eds. Martínez-San Miguel, Y., Sifuentes-Jáuregui, B., Belausteguigoitia, M. Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2016.

Boggs, Vernon W. Salsiology: Afro-Cuban Music and the Evolution of Salsa in New York City. New York: Excelsior Music Publishing Co., 1992.

Duany, Jorge. “Popular Music in Puerto Rico: Toward an Anthropology of ‘Salsa.’” Latin American Music Review / Revista de Música Latinoamericana 5, no. 2 (1984).

Fernández, Raúl A. “The Course of U.S. Cuban Music: Margin and Mainstream.” Cuban Studies 24 (1994): 105–22.

—. From Afro-Cuban Rhythms to Latin Jazz. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006.

Flores, Juan. From Bomba to Hip-Hop: Puerto Rican Culture and Latino Identity. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Green, Douglass M. Form in Tonal Music: An Introduction to Analysis, 2nd ed. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1979.

LeGrand, William Guthrie. "Creating Salsa, Claiming Salsa: Identity, Location, and Authenticity in Global Popular Music.” Master's Thesis, University of Northern Iowa, 2010.

Lodigiani, Irene. “From Colonialism to Globalisation: How History Has Shaped Unequal Power Relations Between Post-Colonial Countries.” Glocalism: Journal or Culture, Politics and Innovation 2 (2020).

Manuel, Peter. “Puerto Rican Music and Cultural Identity: Creative Appropriation of Cuban Sources from Danza to Salsa.” Ethnomusicology 38, no. 2 (1994): 249–80.

Miller, Marilyn. “Plena and the Negotiation of ‘National’ Identity in Puerto Rico.” Centro Journal 16, no. 1 (2004): 36-59.

Mirabal, Nancy Raquel. Suspect Freedoms: The Racial and Sexual Politics of Cubanidad in New York, 1823-1957. New York: New York University Press, 2017.

Negron, Marisol. “Fania Records and Its Nuyorican Imaginary: Representing Salsa as Commodity and Cultural Sign in Our Latin Thing.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 27, no. 3 (2015): 274–303.

Rondón, César Miguel., Frances R. Aparicio, and Jackie White. The Book of Salsa : a Chronicle of Urban Music from the Caribbean to New York City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Yeo, Loo. “The Great Salsa Timeline.” Salsa & Merengue Society, 1999.

Tags

- salsa

- music

- music history

- oiste

- latino

- latino history

- latino heritage

- pathways through salsa

- migration and immigration

- arts culture and education

- us in the world community

- caribbean american heritage

- puerto rico

- cuba

- civil rights

- colombia

- latin america

- african american history

- afro latino

- black history

- culture

- slavery