Last updated: May 4, 2021

Article

More Than “Just” A Secretary

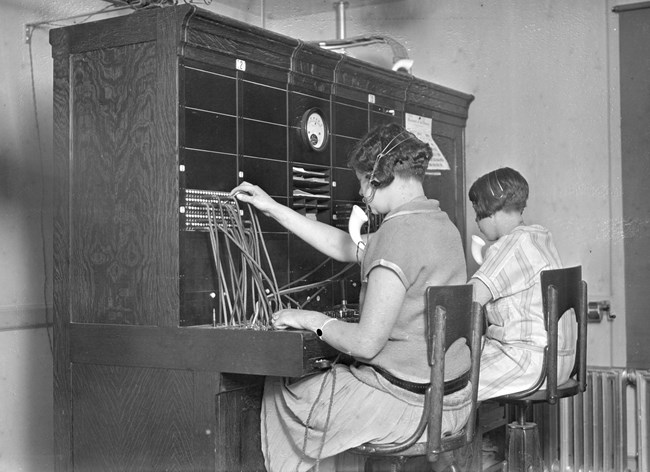

If you’re only familiar with modern office practices, you may not recognize many of jobs necessary to run an office or national park over much of the past hundred years. Today, typewriters have given way to computers, photocopy machines have replaced typing pools, stenographers are rarely seen outside of courtrooms, and callers are largely expected to pick extensions from digital directories. While secretaries and clerks are still linchpins in most offices, dedicated stenographers and switchboard operators have disappeared from the office landscape.

Diving into the Secretarial Pool

Until the 1880s, men were the clerks and secretaries of the United States. By the 1920s, most were women. As industry and government boomed after the Civil War, men moved from office work into construction, mining, and heavy industry. The development of free public high schools in the late 1800s allowed many women to become better educated, although segregated schools were the norm and didn’t provide equal opportunities for all women. Shortages of male workers during World War I played a part in opening these jobs to women, as did stereotypes that women could operate typewriters better due to their smaller fingers and that their domestic and social skills were better suited to secretarial jobs. As women began to dominate the field, these clerical positions went from being important entry-level jobs that led men into management positions to women becoming “just secretaries.”

Getting into the Park Game

Mirroring the rest of the United States, women increasingly became the clerks, secretaries, stenographers, and switchboard operators in national parks and the Washington Office in the 1920s and 1930s. Initially, women weren’t always readily accepted in these roles. For several months in 1921, Yellowstone Superintendent Horace M. Albright and Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer exchanged letters on the subject of women clerks and secretaries. In June, Cammerer wrote recommending a Miss Lonergan as a clerk for Albright. In the letter, he shared several examples of women clerks that he has sent out to parks but remarked, “I don’t want to get too many women into the park game—but there are there are places where they stand up better then men, if they are satisfied as to living conditions.”

By September, Albright’s letter declared, “I am in hope that you can find me a good male clerk. . . I am through with women clerks.” Although he identified one “girl clerk” he was satisfied with, he was unhappy with several others. He described one as lazy and grouchy, noting, “Every time I asked her for overtime work, or Sunday work, she cried like a spoiled child.” In reference to another he stated that she was “a little unreliable and careless, and is certainly fresh and flippant, but I think we might do worse if we tried to replace her now.”

Working and living in remote parks often add additional stresses for many employees. Even today, it can be difficult to get “down time” and avoid the feeling that you’re always on duty, even without a demanding boss expecting you to be available anytime. While some women didn’t stay in these clerical positions longer than a year or two, there were many who thrived in park environments.

The Adventurous Type

National park jobs offered women more than just a steady salary. For many, they offered independence and adventure difficult to find elsewhere at that time. Living and working conditions in parks were primitive by society’s standards, but adventurous women in places like Glacier, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Carlsbad Caverns, Sequoia, Rocky Mountain, and Grand Canyon made crucial contributions to park operations.

The opportunity to travel to national parks held the same appeal for many early NPS women as it does for people today. Beginning in the 1920s, it became easier for unmarried, middle-class White women to travel, although it remained more restrictive for Black and Native American women. Women working in the Washington Office like Isabelle F. Story, Beatrice M. Ward and Edna M. Peltz traveled extensively around the NPS for work and pleasure. Other women like M. Mabel Shaffer were outdoor enthusiasts who made the most of living in a national park when not on duty.

In February 1931, Shaffer skied between Rand Lake and Fern Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park, becoming the first woman to ski across that part of with range within the park boundaries."

Increased mobility also meant that women moved around the country for work. Lulu Hazelbaker transferred from the State Department in Washington, DC, to Glacier National Park in 1921. Helen T. Kinnicott received a promotion from purchasing agent to chief clerk with her move from Yosemite to Carlsbad Caverns in 1929. Clerk Anna Madsen Greer went from the Washington Office to Yellowstone. Margaret Sabin, a clerk at Rocky Mountain, became a senior clerk at Yellowstone after working there during a temporary assignment in the summer of 1929.

Many of these early women only worked for the NPS for a few years, leaving after they got married—or becoming “park wives” if they married fellow employees (Two for the Price of One). Other women such as Francis L. Downs, who worked at Sequoia National Park for 35 years, had long careers in the NPS.

Although they never wore NPS uniforms, these women and many others who came after them made it possible for superintendents to share information with park staff, for the field and the Washington Office to communicate with each other, for employees to be paid and supplies to be purchased, and for parks to share information with the public. Next time you read an early park report or official memo, spare a thought for the unnamed woman who most likely typed it.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.