Last updated: September 28, 2020

Article

Protecting Native Mixed-Grass Prairie at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument

NPS/Victoria Stauffenberg

A sea of grass ripples across the landscape of Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. These grasses are the mixed grass prairie—one of the most endangered habitats on the continent. Changes in land use and increasing human development have fragmented this prairie habitat into isolated protected islands across the Northern Great Plains. Invasive plant species have spread into the prairie, threatening to replace native species, reduce their numbers, and make these plant communities less resilient. Future climate conditions may help spread some of the most problematic invasive species, adding to the challenge of conserving what remains. Fortunately, monument staff and partners are working hard to protect this special habitat. And you can help too. Read on to learn more.

Mixed-Grass Prairie—What Makes it Special?

In healthy mixed-grass prairie, native tall and short grasses, wildflowers, and occasional shrubs grow on fertile soil that resists erosion and has few pollutants. Harmful invasive plants have little to no foothold. These qualities of healthy mixed-grass prairie offer many values:

NPS/Andy Bridges

Feeding and sheltering wildlife

- Grasses and shrubs hide birds and rodents from predators, and buffer them when the weather changes.

- Grass and flower stems, leaves, and seeds feed birds, rabbits, rodents, insects, deer, elk, antelope and others.

NPS photo

Cycling nutrients through the food chain

- Prairie plants anchor the food chain. Grass is food for a grasshopper, which is food for a mouse, which is food for a rattlesnake. The remains of the mouse are broken down by soil insects and microbes, replenishing the soil with valuable nutrients from the mouse’s body to eventually grow new grass.

Scenic beauty

- Waving grasslands transition through shades of green, gold, and hints of purple with the seasons.

At Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, the mixed-grass prairie is important for additional reasons:

NPS photo

Preserving an historically important plant community

- The monument collaborates with the Crow Tribal Historic Preservation Office to preserve the landscape as it existed historically during the Battle of Little Bighorn—in native mixed-grass prairie. While not collected in the park, many prairie plants have ethnobotanical importance to neighboring tribes for food, medicine and ceremonial purposes. All 17 associated tribal groups are consulted about management concerns and projects.

Protecting historical artifacts

- Stable soil and dense vegetation can be an archeologist’s best friend. They slow the flow of water over the ground during storms, preventing erosion that might expose historical artifacts safely buried in the soil. Healthy soil also soaks up and stores more water.

Protecting Native Mixed-Grass Prairie

With so little native mixed-grass prairie left in North America (less than 2%), places like Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument play an especially important role in conservation. While big threats like agriculture and urban development don’t occur inside the monument, other threats loom. Monument staff face several management challenges for the prairie and have a range of potential responses to address them.

Threat: The spread of invasive, exotic plants

Brought into the park by vehicles and shoes, and blown in from surrounding areas, invasive plants outcompete and can displace native grasses and forbs. They can also alter the prairie’s historical relationship with fire. Pernicious species include cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) Japanese brome (Bromus japonicus), St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum), and sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis).

NPS photo

Management actions:

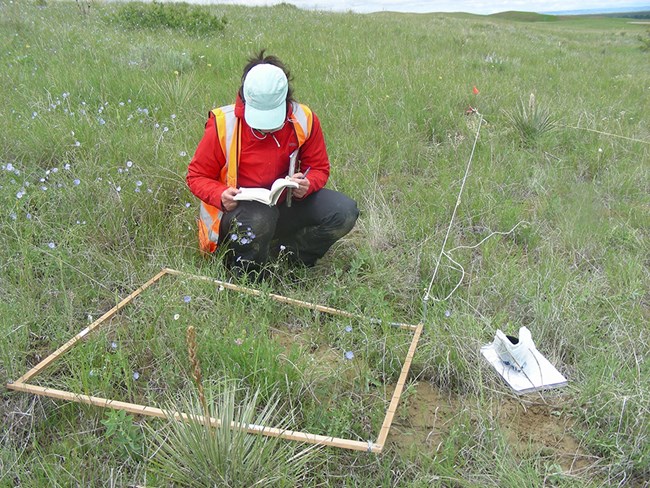

- Monitor grassland health, especially changes in the relative cover of native vs. invasive plants. NPS Rocky Mountain Inventory and Monitoring Network crews survey prairie plots every year.

NPS photo

- Remove invasive forbs using herbicides. Monument staff collaborate with the region’s NPS Invasive Plant Management Team to selectively remove these plants.

- Coordinate with other Northern Great Plains parks and partners on prairie conservation. As part of the Collaborative Adaptive Landscape Management (CALM) project, we have access to the Annual Brome Adaptive Management (ABAM) decision support tool. This tool helps to prioritize the best management strategies for the prairie. We can also learn from other parks’ and partners’ experiences.

What can you do to help?

- Wash your shoes and car before entering the park, and please stay on trails. Report weeds (see below).

Threat: The loss of moderate natural disturbances that historically shaped the prairie

NPS photo

Believe it or not, “disturbance” can be a healthy process in nature. Moderate fires used to move through the prairie every 10–15 years, keeping some invasive grasses in check and preventing too much plant litter from building up. Bison used to graze these prairies, stimulating new plant growth and also keeping some invasive species in check.

Management option:

- Prescribed fire is potentially an appropriate tool for the monument, though its use must be carefully considered by park managers.

Threat: A changing climate

NPS photos

Drier conditions and changes in rain and snowfall patterns are predicted for the region. These changes may favor the spread of invasive, exotic plant species, like cheatgrass.

Management actions:

- NPS scientists nationwide are developing tools that use air temperature and precipitation (rain/snow) information in new ways to help parks understand which plant communities are most vulnerable. This helps managers prioritize actions.

What can you do to help?

- Find educational resources and ways to join the NPS in taking action about climate change at the NPS Climate Change site:

Learn More

Report weeds and learn more about nature in the monument:

406-638-3225

https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/nature/index.htm

Explore Rocky Mountain Network vital signs monitoring in national parks:

https://www.nps.gov/im/romn/upland-vegetation-and-soils.htm

Download a pdf of this article.

Prepared by Sonya Daw and Erin Borgman, Rocky Mountain Inventory & Monitoring Network

Tags

- little bighorn battlefield national monument

- mixed-grass prairie

- invasive non-native species

- climate change

- conservation

- resource management

- inventory and monitoring

- tribal historic preservation program

- rocky mountain network

- romn

- im

- grasslands

- battlefield

- cultural landscapes

- invasive species

- science

- invasive plants

- climate change effects

- plants