Last updated: September 30, 2025

Article

President Grant and the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act

Wikimedia Commons

On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law. This significant act established the concept of a “National Park.” As stated in the original legislation, the Yellowstone area in present-day Wyoming and Montana would be “reserved and withdrawn from settlement, occupancy, or sale under the laws of the United States.” Rather than developing the area for private industry or home construction, Yellowstone would be set aside as a “public park or pleasuring-ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Since the passage of the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act, the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service have worked to preserve more than 420 different sites around the United States that have been deemed as nationally significant for their natural and cultural qualities.

Ulysses S. Grant never visited Yellowstone. He wasn’t a vocal advocate for conservation, nor did he offer any comments about the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act after signing it into law. However, Grant’s experiences with the U.S. Army allowed him the chance to see more of the American West than most people at that time. During the 1850s, Grant was stationed at Columbia Barracks (now Fort Vancouver) in Washington Territory and at Fort Humboldt in northern California. In July 1868, General Grant accompanied Generals William T. Sherman and Philip Sheridan for a two-week tour that included stops in Nebraska, Dakota Territory, and Colorado. His sons Frederick and Ulysses, Jr. (“Buck”) also joined the trip. In two letters to his wife Julia, Grant discussed how “Sherman, Sheridan, Fred [,] Buck & myself each carry with us a Spencer Carbine and hope to shoot a Buffalo and Elk before we return,” and that they were anxious to see gold mines within the Rocky Mountains. Grant also expressed interest in seeing “wild horses, Buffalo, wolf, & antelope” during the trip. These experiences may have influenced Grant’s decision to sign the Yellowstone legislation into law four years later.

Library of Congress

While some Westerners expressed concern about the need to protect natural and cultural resources in their region, historian Richard Sellers argues that Congress was more interested in extracting resources and promoting tourism to the West than in promoting conservation. Businessman Jay Cooke was particularly interested in this effort. As the owner of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company, he hoped to extend its lines from Dakota Territory into Montana Territory, including the area that now encompasses Yellowstone. These efforts would bring jobs, industry, and tourists to the area. By closing off Yellowstone to settlement through law, Cooke aimed to grab a significant portion of the profits that could come from developing the tourism industry.

Three major expeditions to Yellowstone raised public awareness of the area’s natural beauty and significance. The 1869 Folsom-Cook-Peterson Expedition, 1870 Washburn-Doane Expedition, and 1871 Hayden Expedition all garnered interest from the press and from scientists who were anxious to study Yellowstone. The Hayden Expedition was particularly notable. Ferdinand V. Hayden was the head of the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. He brought a team of scientists, photographer William Henry Jackson, and artists Henry W. Elliot and Thomas Moran along for the journey. The combination of scientific studies, photographs, and artwork did much to convince Congress of Yellowstone’s value. In fact, numerous sketches by Moran were displayed at the U.S. Capitol building throughout 1871.

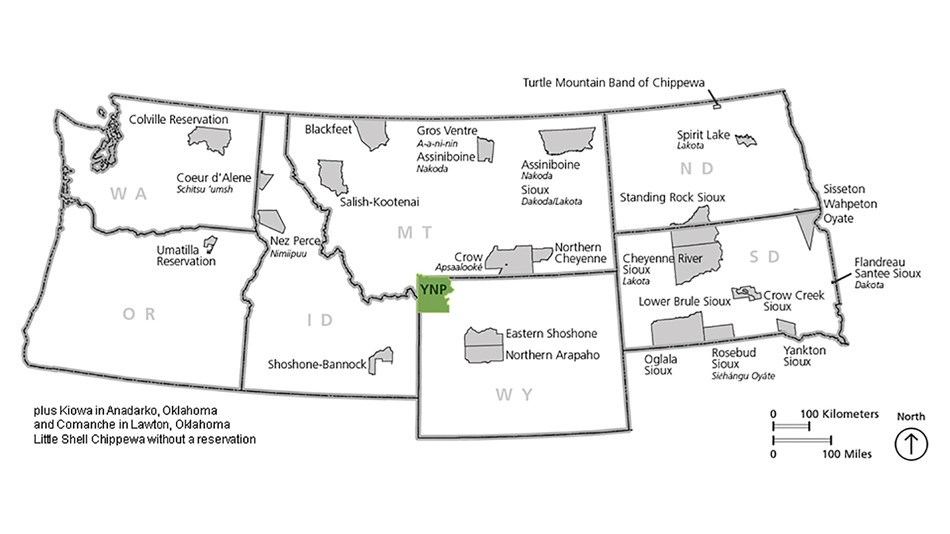

National Park Service staff at Yellowstone National Park estimate that human occupation in the Yellowstone region dates to perhaps as much as 15,000 years ago with the Tukudika (Sheep Eaters) people. Twenty-seven current Tribes have historic connections to Yellowstone. However, the passage of the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act led to the forced removal of Indigenous Tribes who lived in and around the Yellowstone area. Historian Mark David Spence argues that the creation of national parks must be connected to the removal and confinement of Native peoples to reservations. As more settlers and businesses (such as the Northern Pacific Railroad) moved to the West, the federal government worked to move Native people to reservations. The forced removal to reservations was part of a larger process of destroying Tribal sovereignty and “civilizing” Native Americans to become Christian farmers whose loyalty was to the U.S. government, not their respective Tribe.

Yellowstone National Park/National Park Service

For Tribes in the Yellowstone area such as the Blackfeet, Crow, Kiowa, Nez Perce, Cheyenne, and Shoshone-Bannock, the closing off of Yellowstone meant the loss of important hunting grounds, living space, and lands of great spiritual significance. As Spence argues in Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks, “What [Ansel] Adams’s photographs and what tourists, government officials, and environmentalists fail to remember is that uninhabited landscapes had to be created.” In other words, the creation of pristine public spaces for tourists to enjoy natural landscapes came at the expense of removing Native Americans from those spaces. An important part of the National Park Service’s mission today involves acknowledging this history and celebrating Tribal connections to areas that are part of the agency today.

The establishment of Yellowstone National Park did not immediately lead to the creation of more public lands. Sellars points out that Yellowstone’s establishment was an anomaly for its time. It took almost twenty years for Congress to establish additional public lands in the form of Sequoia, Yosemite, and General Grant National Parks in California. While tourism and industry continued to be of interest to supporters of new national parks, a growing interest in conservation nevertheless played an important role in expanding the national parks movement during the twentieth century, including the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916.

Further Reading

Sellars, Richard West. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Spence, Mark David. Dispossessing the Wilderness: Indian Removal and the Making of the National Parks. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Yellowstone National Park, “Park History.”