Last updated: January 9, 2025

Article

Plains Train Depot Cultural Landscape

NPS / WLA Studio

Introduction

Usually, a train depot is a passing-through place. People and goods come and go. Some make their connections, others don’t. On our way from our point of departure to our destination, we're usually too preoccupied with where we’re headed to take much notice of the spaces in-between.

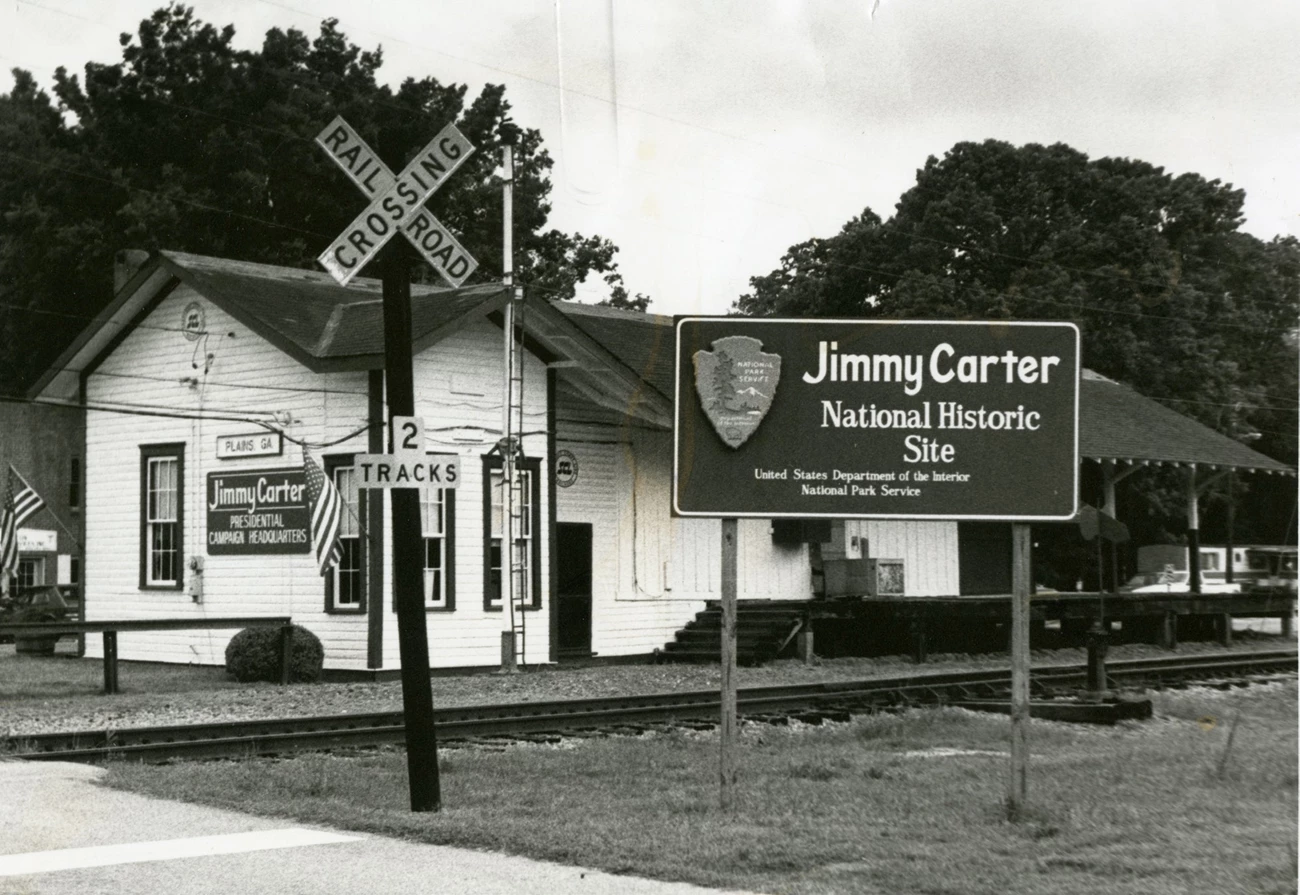

And yet, to linger and take notice is exactly what you’re invited to do at the Plains Depot in Plains, Georgia. A unit of the Jimmy Carter National Historical Park, the Depot stands today as the most recognizable symbol of Carter’s remarkable 1976 presidential campaign, when a peanut farmer from rural south Georgia made his way to the White House.

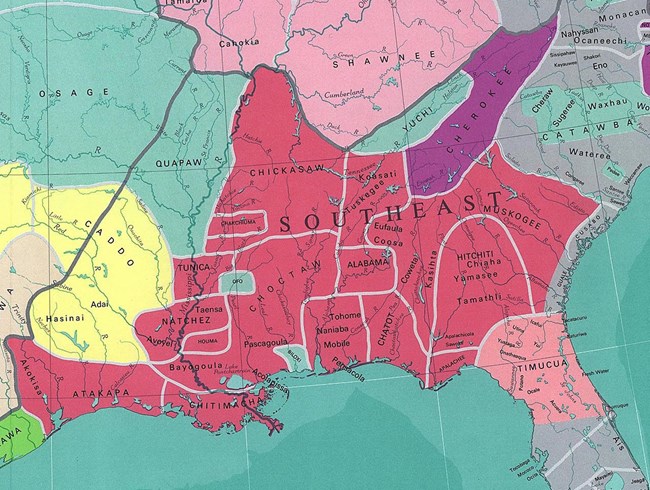

Sturtevant, William C, and U.S Geological Survey. National atlas. Indian tribes, cultures & languages: United States. Reston, Va.: Interior, Geological Survey, 1967. Library of Congress.

Early History and Development

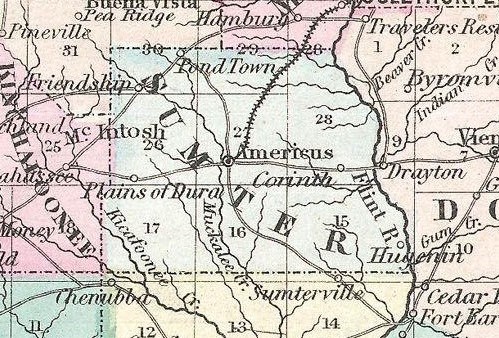

The lands on which the Plains Depot was built were formerly occupied by the Creek Confederacy.[1] The U.S. government forced the ceding of this land through a series of coercion tactics concluding with the Indian Removal Act in 1830. Thereafter, Plains of Dura (now known as Plains) developed as a small agricultural village on the western outskirts of the territory henceforth known as Sumter County, Georgia.

Soon, new settlers established satellite communities in the vicinity of Plains of Dura. Antebellum development took the form of plantation agriculture centered on cotton and textile production dependent on the labor of enslaved African Americans. The Civil War not only ended the practice of wholesale slavery but also destroyed much of the railway infrastructure on which the plantation economy had depended.

It was not long, however, before railroad executives and investors leveraged the situation. As the post-war railroad construction boom gained momentum, new lines were extended into new, previously unserviced areas like western Sumter County. In 1884, the Americus, Lumpkin, and Preston (AP&L) Railroad was chartered. By 1886, the company’s tracks had reached the vicinity of Plains of Dura.

“Georgia.” Published by J.H. Colton & Co. No. 172 William St. New York. Entered 1855 by J.H. Colton & Co. New York. No. 29. Cartography Associates, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection (Creative Commons License).

The constellation of rural townships surrounding Plains of Dura re-consolidated themselves as the Town of Plains in April of 1890 and relocated nearer to the new AP&L line. Of course, to be a railroad town you first need a depot – hence, the Plains Depot was one of the first buildings constructed within the newly consolidated town.

Jimmy Carter, Early Life & Influences

In 1928, Jimmy Carter’s family moved to a 360-acre farmstead in Archery, a historically African American community on the outskirts of Plains. Carter's early life in Archery offers a window into the evolution of race relations, agricultural production, and politics in Plains and the ways it paralleled patterns seen throughout the greater South. Carter also had a lifelong association with the Plains Depot – as a boy, he often played at the station and caught rides on trains to Americus, the next town over, to go to the movies.

Though Black and White people in the rural South relied on one another to work towards common goals, the fruits of their labor were unevenly distributed under the sharecropping system that had succeeded plantation slavery as the predominant socioeconomic system in the region.

James Earl Carter, Sr. – Jimmy Carter’s father – employed 200 Black men and women to work his 4,000 acres of farmland. Thus, Jimmy Carter’s early life was characterized by close contact with rural working-class African Americans. Carter specifically recalled that his childhood was “shaped by black women” – he played with their children, sat at their dinner tables, and learned the key lessons of his boyhood by working side-by-side with them and their husbands.

Living in close proximity to rural, working-class African Americans would later influence Carter’s progressive attitudes toward race relations as a politician, distinguishing him from the avowed segregationists who had come to dominate Georgia politics. Despite stiff resistance from these entrenched interests, Carter quickly gained notoriety, serving both as a Georgia state senator (1963-1967) and governor of Georgia (1971-1975).

“Old Railroad Depot (Carter Headquarters)” [postcard] Published by the Sandcraft, photograph by Charles W. Plant, presented in the NPS Cultural Landscape Report.

NPS / Jimmy Carter National Historic Site Archives

Jimmy Carter, from Plains to the Presidency and Back

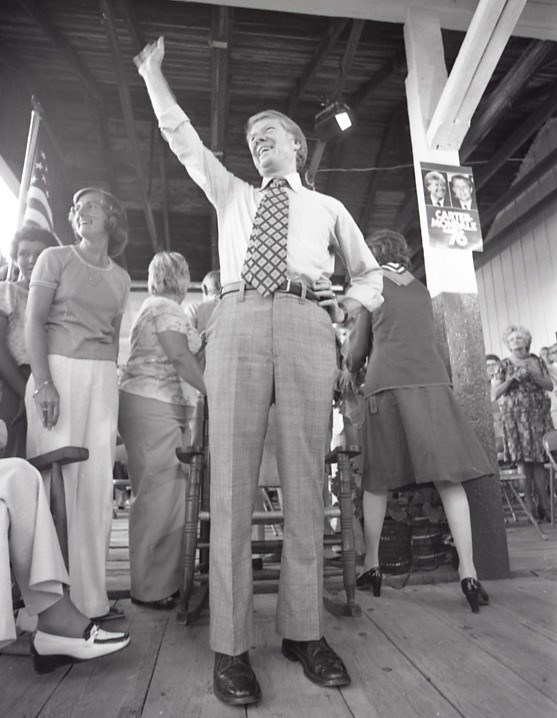

By the 1950s, the Plains Depot had drifted into dilapidation. When Carter designated the Depot as his official presidential campaign headquarters, however, the building’s notoriety skyrocketed on a trajectory mirroring Carter’s own rapid ascent.

The Plains Depot proved a powerful symbol for the Carter campaign. With its rustic charm, the Plains Depot embodied an America that remained relatable to many and idealized by others since removed from small-town life. To Plains residents, it remains the literal and figurative heart of their community.

Local residents, friends, and relatives of the Carters took it upon themselves to retrofit the interior of the building to suit the campaign team’s needs. Volunteers also decorated its exterior with “Carter” green trim, installed Crape myrtles (Lagerstroemia indica) and evergreen shrubs underlain by pine straw mulch, and laid a gravel parking lot.

Following decades of neglect, the Depot was once again put to its intended use on January 19, 1977, the day before Carter’s inauguration, when more than 100 campaigners boarded a train bound for Washington D.C.’s Union Station. It was the first time the tracks had been used for passenger transport since 1951.

Landscape Description

Today, the Plains Depot landscape closely resembles its former state as the Carter campaign’s official headquarters. Defining characteristics of the site include its spatial organization, circulation, architecture, and views.

NPS

At ground level, the site’s spatial organization consists of three parts: the gravel parking area, the depot building itself, and a small area of turfgrass. At the site level, the railroad tracks running east-west off the site's northern property line act as an additional organizing element. As a defining feature of the Depot’s historic function, the tracks also represent a key circulation feature.

Historically, the depot site was sparsely vegetated. The only known ornamental vegetation was not introduced until 1976, when campaign workers installed a bed of broadleaved evergreen shrubs and crape myrtles east of the depot building. Most of this installation has since been removed, though one crape myrtle survives. Today, site vegetation is mostly characterized by turfgrass.

The Plains Depot building itself is a vernacular-style, single-story wood structure with an addition on its east side. A distinguishing feature is its over-sized gabled roof, which overhangs the north and south ends of the building and covers a large open-air loading platform on its west side.

The site is also characterized by several distinctive views to and from the Depot and downtown Plains. These views remain much as they were during the 1976 presidential campaign.

Preservation and Treatment

In 1986, the CSX Corporation donated the building to the Plains Historical Preservation Trust. On December 23, 1987, Public Law 102-206, 101 authorized the Jimmy Carter National Historic Site. The Plains Historical Preservation Trust then donated the depot to the National Park Service in 1988. The site was renamed as Jimmy Carter National Historical Park in January of 2021.

NPS / Jimmy Carter National Historic Site Archives

The National Park Service’s stewardship over the last 30 years has ensured that the Depot continues to convey the entwinement of Jimmy Carter’s life with Plains’ developmental history. Notable changes made by the Park Service include the removal of a remaining railroad spur line in the 1980s as well as the addition of a walkway and a universal access ramp in 1998. In 2007, the northernmost crape myrtle was removed as part of utility work.

In December of 2019, a Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) was completed for the Plains Depot in order to articulate a long-term management strategy for the site. Under an integrated philosophy of preservation and rehabilitation, the main treatment goals for the site today are to “maintain and enhance the overall aesthetic of the 1976 campaign period set in the context of downtown Plains by rehabilitating the historic composition of the landscape.”

Conclusion

For the numberless passersby who preceded Jimmy Carter, Plains Depot was like any other in a south Georgia railroad town – a fixture of life, something you could set your watch against. With the announcement of Carter's candidacy for the Presidency in 1974, the Depot became a nexus of national attention and a point of departure from one point in the would-be President’s life to the next – from the life of a peanut farmer’s son turned politician to 39th President of the United States.

NPS / WLA Studio

The scene of the campaign's sucessful rise in the 1976 election season shares the landscape with the subtler legacies on which the Depot was also built: first, the cessation of Muskogee (Creek) territory, its role as a transportation hub in an agricultural economy dependent on the labor of enslaved workers, then an exploitative sharecropping system where few managed to break even and most eked out only the basest living.

Though legally enforced segregation made it so that White and Black people lived separately, the challenges and hardships of rural life gave them no choice but to learn to get on. The vaulting of small-town life in the rural South to the national stage during the 1976 election brought with it not only the reminder that every state had its Plains, but also that such neighborliness might be possible at a grander scale. Though long since decommissioned as a functioning railway hub, the Plains Depot nonetheless continues to serve as a reminder of the connections between histories and people.

“Plains Train Depot” by Kenneth P. Craig, from the Jimmy Carter NHS museum collection [JICA 6927]

[1] Today, the tribe is federally recognized as the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. See the Muscogee (Creek) Nation's website for further information.

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Vernacular

- National Register Significance Level: Local and National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C

- A (local level) in area of community planning and development for role in historic development of Plains, GA

- C (national level) for association with Carter Presidential Campaign and Carter’s 1976 Presidential inauguration

- Period of Significance: 1976