Last updated: August 24, 2022

Article

Places of Public Health: Medical Research during World War II

—President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on the opening of the new National Institutes of Health campus, October 31, 1940

Public domain. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

On the eve of World War II in the United States, government officials began preparing the country for total war. In addition to training soldiers and advancing industry, the US Military was concerned about the health of its soldiers and homefront workers. Treating disease was more expensive and time-consuming than preventing disease outright, so the US military partnered with science and industry to invest in life-saving medical research. Investing in preventatives meant less resources would be spent treating illness, and soldiers would spend less time in hospitals. Additionally, a healthy workforce meant production hours were not lost to sick days.

Only decades before, World War I had exposed a serious public health deficiency. Many men were unfit for military service due to medical issues. The movement of soldiers in 1918 had also helped infect millions of people worldwide with influenza. Officials worried about another influenza outbreak, or another disease that could decimate both the military and the workforce. There was also a concern that disease could be used as a bioweapon by enemies. These factors put additional pressure on the US Government to invest in medical research before the United States was brought fully into the war.

The war touched nearly every citizen across the globe, and forced ingenuity and inventiveness in every industry. The following medical research facilities are a sampling of the facilities whose innovation made significant advances to military and civilian medicine. Several of these places were surveyed through the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) program, which allows researchers to study buildings through measured drawings, photographs, and written histories. These surveys enable us to learn about buildings even if they are now modified or gone.

Photo by Walter Smalling, Jr. Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

1. Industrial Hygiene Building, National Institutes of Health: Bethesda, MD

The National Institutes of Health was dedicated on October 31, 1940, with a moving speech from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In his speech, Roosevelt expressed that this new facility emphasized peace, and that the medical research performed here would benefit all. With the political situation worsening in Europe, listeners understood his underlying meanings. War meant that the world’s health would suffer, and medical research would be needed to fight against wartime conditions. This speech gave a much larger context to the work that would be conducted at the new laboratories.

Although the new laboratories encompassed different areas of research, the Industrial Hygiene Lab would benefit war workers the most in the years to come. Scientists researched the effects of noxious fumes, dust, and other workplace hazards that could impact the wellbeing—and efficiency—of the worker. Researchers relayed their findings to the Division of Industrial Hygiene. These standards served as the precursor to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards.

The basement of the Industrial Hygiene Building also held a pressure chamber. This machine was able to reproduce conditions at different altitudes. Observing humans allowed researchers to study the effects of steep climbs and deep dives on the body, while remaining at ground level. They could also see how mechanical equipment functioned at different altitudes.

The entire National Institutes of Health complex, including the Industrial Hygiene Building, was surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1994. Cutting-edge medical research that benefits the nation is still done here in the 21st century.

Public domain. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

2. Rocky Mountain Laboratories: Hamilton, MT

Public health research began at Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML) at the beginning of the 20th century. Researchers were trying to isolate the cause of spotted fever, a disease that had terrified the local populations. In 1906, Dr. Howard Ricketts concluded that spotted fever was transmitted by the Rocky Mountain wood tick. Work began afterwards to produce a vaccine to protect against spotted fever. In 1937, the laboratory became part of the National Institutes of Health system.

By the outbreak of World War II, RML had multiple buildings and a large staff dedicated to producing vaccines. In 1940, the labs became a “national vaccine factory,” creating vaccines for typhus and yellow fever. Mobilization of troops created atmospheres susceptible to disease and transmission, so outbreaks of these diseases were anticipated. To make these vaccines, the lab required fertile chicken eggs. The lab partnered with local chicken farmers, who provided the lab with 2,600 dozen eggs per month.

Initially, Rocky Mountain Laboratories only produced vaccines for civilian use. In 1942, they began producing for the military as well. By the end of the year, RML produced nearly a half a million typhus vaccines and over one million yellow fever vaccines. By August 1945, almost ten million yellow fever doses had been distributed. These refrigerated doses traveled from Montana by either train or airplane to their destinations around the world. Despite increased production, Rocky Mountain Laboratories operated with a smaller staff during the war, as many workers joined the war effort. Some even continued working in medical research capacities worldwide.

The Rocky Mountain Laboratory District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 1, 1988. It was surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1995. Today, scientists at RML laboratories continue to study infectious diseases and biodefense measures.

Carol Ann Poh, NPS Photo, 1973.

3. The Rockefeller Institute: New York City, NY

The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research was founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1901 as a place “to conduct, assist and encourage investigations in the sciences and arts of hygiene, medicine and surgery, and allied subjects, in the nature and causes of disease and the methods of its prevention and treatment.”[1] The first building on the New York campus opened on May 11, 1906. From its earliest days, The Rockefeller Institute made finding a vaccine for yellow fever a priority. It would take nearly three decades to do so. Finally, in 1937, virologist Max Theiler created a successful vaccine, which he named 17D. Soon after, 17D would be in demand as the US prepared to mobilize its forces overseas.

With war approaching, the US Army approached the Rockefeller Institute. They asked them to increase their production of the yellow fever vaccine for the military. Moved by patriotic duty, Rockefeller Foundation President Raymond Fosdick offered to immunize the entirety of the armed forces free of charge. The Rockefeller Institution produced 4 million yellow fever vaccines in 1941. By the end of 1945, 34 million doses had been produced and distributed around the world.

Founder’s Hall of the Rockefeller Institute was added to the National Register of Historic Places and it became a National Historic Landmark on September 19, 1974. The building is now part of the Rockefeller University campus.

4. The Mayo Clinic: Rochester, MN

The Mayo Clinic began conducting research relating to aeromedicine in 1918. At the onset of World War II, the Mayo Aero-Medical Unit was established to study the effects of oxygen and gravity on the human body during flight. These physicians and scientists worked in secret for the US Government as “dollar-a-year men.” This meant that for all their research, the US Government paid them $1 per year, and was seen as a patriotic measure. “Dollar-a-year-men” donated their time and resources in their chosen industry to further the war effort. Although the phrase coined at the time was “dollar-a-year men,” women worked in the Aero-Medical Unit as well.

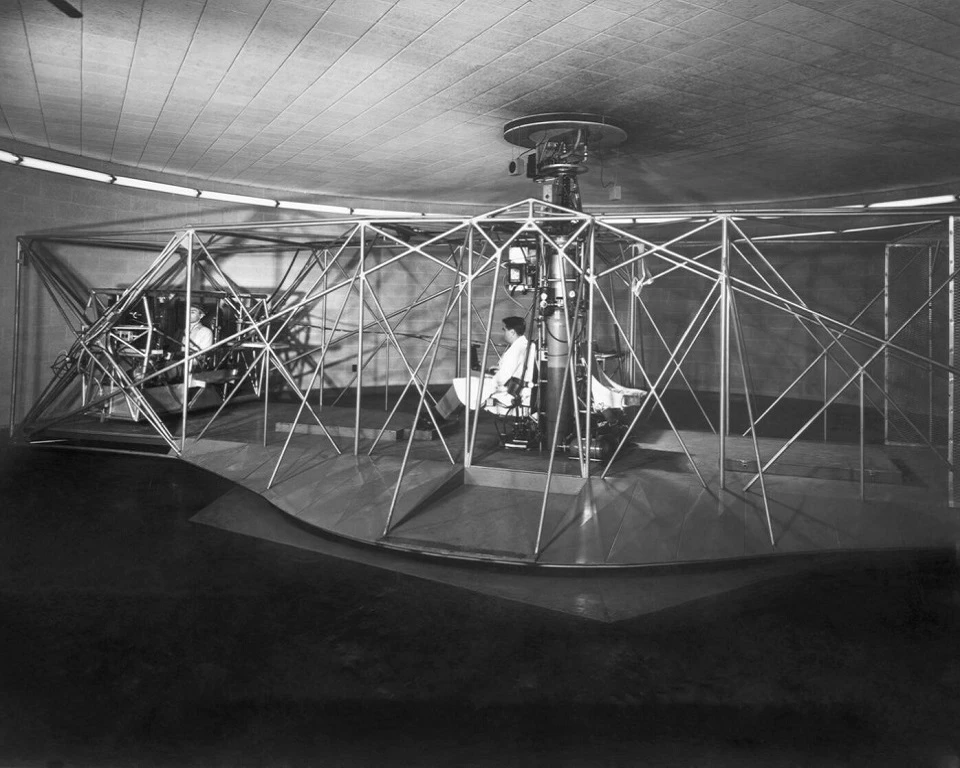

To study the effects of pressure and oxygen, the Mayo Clinic built the first civilian pressure chamber. They then recruited the help of volunteers to enter the chamber. The most famous participant in this study was aviator Charles Lindbergh. To study the effects of gravity, the Mayo Clinic built a human centrifuge and recruited even more volunteers to “take flight” in the machine. More than 300 volunteers took over 10,000 rides in the machine, including the doctors and scientists leading the experiment.

Left image

This centrifuge simulated flight conditions for aero-medical research.

Credit: Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved.

Right image

Charles Lindbergh volunteering in the pressure chamber.

Credit: Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved.

Because flying places a lot of pressure on the body, pilots would often suffer a lack of oxygen to their brains and lose consciousness. Through these studies, the Aero-Medical Unit formulated a series of techniques and inventions to help aviators remain conscious. One technique was called “the Grunt,” or “M-1” (Mayo-1). Pilots contracted their muscles to push blood up to their brain, keeping them conscious. This technique is still used in pilot training today. “The Grunt” was helpful, but scientists wanted to develop a system that didn’t require pilots to consciously think about their oxygen supply.

The Aero-Medical Unit took their idea of aiding blood flow to the brain, and developed pressurized flight suits. Called G-suits, these suits counteracted the G forces placing pressure on pilots’ bodies. They also developed oxygen masks and “bailout bottles.” These tools ensured pilots had an adequate supply of oxygen during flying—and bailing out of a plane. Wilhelm Messerschmidt, the top German fighter plane designer, saw a G-suit on a US aviator downed in Europe. He stated after the war: “We had nothing to match it, and I knew, if American aviation science was so far ahead of us to make such a suit, Germany had lost the war already.”

The Mayo Clinic continued their research on aeromedicine through the 20th century and is still a center of progressive research today. The Mayo Clinic buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places and became a National Historic Landmark on August 4, 1969. The Plummer Building, which held the Mayo Clinic after the building opened in 1928, was surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1989.

Photo by Theodor Horydczak. Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

5. Naval Medical Research Institute, National Naval Medical Center: Bethesda, MD

Only a few days after dedicating the new National Institutes of Health campus, President Franklin Roosevelt laid the cornerstone for the new National Naval Medical Center located across the street. The president himself had chosen the design and created a rough plan for the facility’s architectural style. The complex was established as a place for research and dissemination of medicine related to naval service.

The areas of research studied here were very diverse and intended to directly solve the issues faced by service members in the Navy. Some projects studied improved equipment for sailors. Researchers worked to create an anti-exposure suit to protect service members submerged in cold water for extended periods of time. Another project improved designs for lifejackets and stretchers to aid in rescue operations. Teams also researched the physiological problems associated with naval service. Project teams studied the effects of various gasses on the body in order to create a successful protocol for submersion and ascension in water. Researchers also developed preventative methods for seasickness and immersion foot (better known as trench foot).

Today, the complex serves as Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, one of the foremost medical facilities for the military in the United States. Building No. 1 of the National Naval Medical Center was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 1977.

The content for this article was written and researched by Hannah Haack, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education and the Park History Program.

[1] John Kobler, The Rockefeller University Story (New York: The Rockefeller University Press, 1970), 5-6.

Brierton, Joan, Carol Hooper, Elizabeth Lampl, Kristen Fetzer, and Judith Robinson. “National Institutes of Health, Industrial Hygiene Laboratory.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1994. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MD-1102-A). Accessed July 17, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/md/md1400/md1452/data/md1452data.pdf.

Bruce, Judd and Bridget Maley. “Rocky Mountain Laboratories.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1995. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MT-101). Accessed July 17, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/mt/mt0300/mt0320/data/mt0320data.pdf.

Collins, Francis. “NIH at 80: Sharing a Timeless Message from President Roosevelt.” National Institutes of Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. October 29, 2020. https://directorsblog.nih.gov/tag/world-war-ii/.

Earle, Lawrence P. “Bethesda Naval Hospital Tower Block.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1977). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/106777777.

Goldberg, Barry. “The Long Road to the Yellow Fever Vaccine.” RE:SOURCE. Rockefeller Archive Center. November 2, 2019. https://resource.rockarch.org/story/the-long-road-to-the-yellow-fever-vaccine/.

Hettrick, Gary R. “Vaccine Production in the Bitterroot Valley during World War II: How Rocky Mountain Laboratory Protected American Forces from Yellow Fever.” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 62, no. 4 (2012): 47–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24414669.

Kobler, John. The Rockefeller University Story. New York City, NY: The Rockefeller University Press, 1970.

Lavoie, C. “Mayo Clinic, Plummer Building.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1989. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MN-80). Accessed July 19, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/mn/mn0100/mn0129/data/mn0129data.pdf.

Lyons, Michele. 70 Acres of Science: The NIH Moves to Bethesda. Bethesda, Maryland: National Institutes of Health, 2006. https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/70acresofscience.pdf.

Mayo Clinic. “Department of Defense Medical Research Office - History.” Research. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.mayo.edu/research/centers-programs/department-defense-medical-research-office/history.

Mayo Clinic Contributions to Medicine. “Late 1930s-Mid-1940s: Secret Research Transforms Aviation.” Accessed July 28, 2022. https://mccms.cws.net/content/history.mayoclinic.org/files/1930.pdf.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “History of Rocky Mountain Labs.” About. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/rocky-mountain-history.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “Rocky Mountain Labs Overview.” About. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/rocky-mountain-overview.

Naval Medical Research Institute: National Naval Medical Center, Bethesda, Maryland. Bethesda, MD: Naval Medical Research Institute, 1949. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14322040R-bk.

Poh, Carol Ann. “The Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1974). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/75315970.

The Rockefeller University. “Our History.” About. Accessed July 19, 2022. https://www.rockefeller.edu/about/history/.

“Rocky Mountain Laboratories Historic District.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1988). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/71975428.

Shilling, Charles W., and Jessie W. Kohl. History of Submarine Medicine in World War II. New London, CT: U.S. Naval Medical Research Laboratory, 1947. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-35410810R-bk.