Last updated: February 20, 2024

Article

Petroglyphs, Pictographs, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, wrote about the petroglyphs and pictographs they saw during their journey. Sometimes, Native peoples interpreted the markings for the corps members. They explained that the markings were for navigation, communication with the spirits, and part of social and ceremonial practices. Other times, the corps members encountered rock markings that appeared abandoned and had no apparent association with tribes nearby.

(For readability, the Corps members’ quotes below are lightly edited from the authors’ original writings.)

The corps members documented something special and largely lost to modern eyes: a context for petroglyphs and pictograph markings among other marks on trees, human bodies, objects, and in villages. Some people they met wore body paint, particularly red and white. For instance, the corps members recounted a friendly encounter with a group of warriors. The head man was painted white, while the others were painted in different colors. After dark, the corps members made a large fire for a war dance and “all the young men prepared themselves for the dance. Some of them painted themselves in curious manner[.] Some of the Boys had their faces & foreheads all painted white & c [.]” They took turns recapping what “he had done in his day, & what warlike actions he had done & c.”

Clark wrote about two ceremonial stones manipulated to communicate with spirits. On the Chess-che tar (or Heart) River, there was “a Smooth Stone which the Indians have great faith in & Consult the Stone on all great occasions which they Say Marks or Simblems [symbol + emblems] are left on the Stone of what is to 〈pass〉 take place & c.” At Medicine Hill, Native peoples visited a stone every spring and sometimes in the summer “to know What was to be the result of the ensuing year [.]” The Native people gave smoke to the stone, then withdrew to a nearby wood to sleep. The next morning, they would return to the stone and “find marks white & raised on the Stone representing the piece or war which they are to meet with, and other changes, which they are to meet[.]" Curiously, a nearby sandstone outcrop is covered with pictographic paintings and petroglyphic carvings. Did Native peoples have a similar expectation for rock markings, that they could communicate with the spiritual world through rock surfaces?

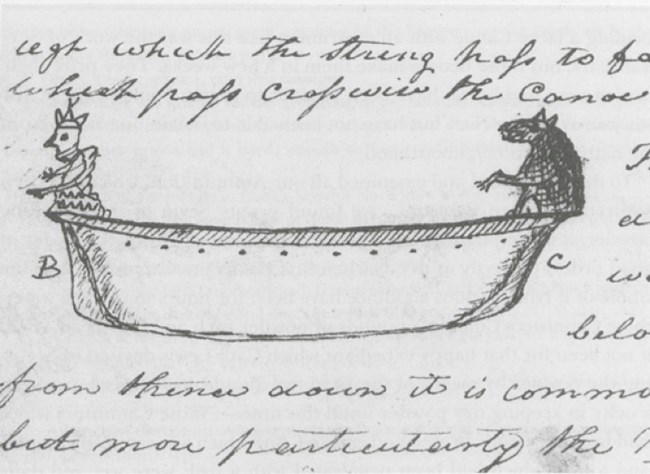

The corps members often observed painting and sculpture in places old and abandoned or still inhabited. Clark, in particular, tried to extrapolate their significance. Exploring near Beacon Rock, Clark on 31 October 1805 observed an “old deserted village” where he found “8 Vaults for the Dead” covered in “broad boards Curiously engraved” and a “great many wooden gods, or Images of men Cut in wood” on the south side of the vaults. Clark could not “learn certainly if those people worship those wooden images, they have them in conspicuous parts of their houses[.]” In his 1 February 1806 journal entry near Fort Clatsop, Clark described canoes “[…] waxed painted and ornamented with curious images on bow and Stern; those images sometimes rise to the height of five feet […]” and […] their images are representations of a great variety of grotesque figures […]”.

Scenes like this raise questions we cannot answer. Did rock markings mirror ceremonial or social practices also carried out in human everyday life? Did the color of figures in pictographs correlate with rank or importance of each figure? Were these markings all connected? If so, their meanings are unclear today.

Tavern Cave

The Corps departed from St. Charles, Missouri on 21 May 1804. Two days later, on 23 May, William Clark observed pictographs near the mouth of Tavern Cave. Clark described, “we passed a large Cave on the Lbd. Side (Called by the French "the Tavern") about 120 feet wide 40 feet Deep & 20 feet high many different images are Painted on the Rock at this place. The Inds & French pay homage. Many names are wrote on the rock[.]” Clark marked his name beside the others.

Moniteau Creek

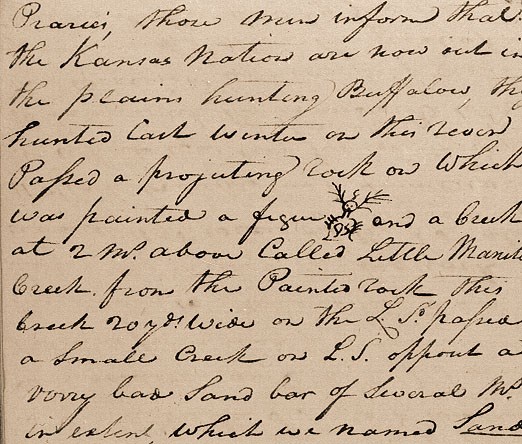

On 7 June 1804, the Corps stopped at the mouth of Moniteau (or Manitou) Creek, now called Manitou Bluffs. Clark described, “[…] a Short distance above the mouth of this Creek, is Several Curious Paintings and Carving in the projecting rock of Limestone inlaid with white red & blue flint […]” John Ordway saw, a “a high Cliffs of Rocks on which was picture of the Devil on South Side of the River.” And wrote Charles Floyd, “N. Side where the pictures of the Devil and other things.” Manitou and Moniteau are variations on the Algonquian name for the Great Spirit.

Nemaha River

The Corps took a day of rest on 12 July 1804 along the Ne-Mah-Ha (Big Nemaha River). Clark hiked up an “Artificial Mound” from which he observed, “Mounds or ancient Graves which is to me a Strong evidence of this Country having been thickly Settled [.]” A couple of miles further, he “[…] observed Some Indian marks, went to the rock which jutted over the water and marked my name & the day of the month & year […].”

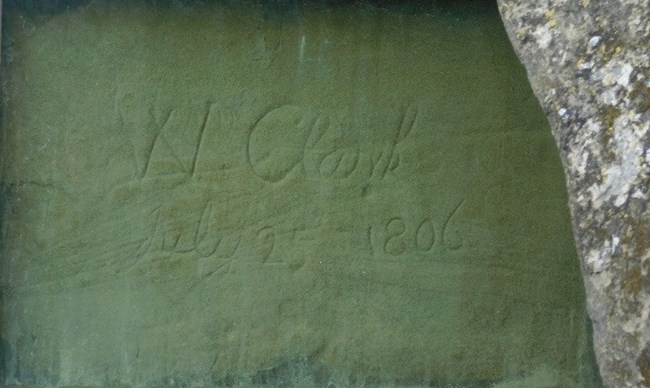

Pompey’s Pillar

On 25 July 1806, Clark and Toussaint Charbonneau, Sacagawea and their son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, York (a Black man enslaved by Clark), and nine other men passed a rock landmark while traveling along the Yellowstone River. Clark named it “Pompy’s Tower” (now called Pompey’s Pillar). He described it as: “200 feet high and 400 paces in circumference and only accessible on one Side which is from the N. E the other parts of it being a perpendicular Clift […]. The Indians have made 2 piles of Stone on the top of this Tower. The natives have engraved on the face of this rock the figures of animals &c. near which I marked my name and the day of the month & year.”

Interested in going on your own voyage of discovery? Explore the Corps’ journals to see what you discover and take a trip to parks.

Lewis & Clark National Historical Park

Lewis & Clark National Historic Trail

Travel the Lewis & Clark Expedition

Help the National Park Service and its partners preserve and protect these fragile resources. Please do not disturb the petroglyphs or pictographs, or carve or paint on top of them. Your assistance helps ensure that you and future visitors can continue to appreciate these special markers of the story of Native peoples and Lewis and Clark.