Last updated: March 8, 2025

Article

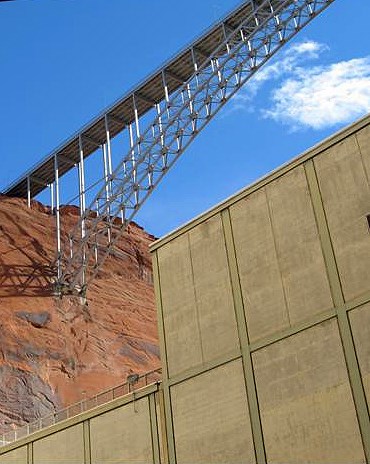

Parks Look for Ways to Alleviate Glen Canyon Dam’s Downstream Impacts

Vegetation experiments are helping restore Colorado River sites in Grand Canyon and Glen Canyon.

By Lonnie H. Pilkington, Joel B. Sankey, Daniel L. Boughter, Taryn N. Preston, and Cam C. Prophet

Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey / Joel Sankey

Regardless of the location, time of day, or season, the grandeur of Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area inspires awe. Visitors can reflect on the sunlit colors of the towering canyon walls or witness the vibrant, golden display of Fremont cottonwood leaves each fall.

For millions of years, the Colorado River has sculpted canyon country; for thousands of years, it has been a lifeline for humans, wildlife, and plants. But despite its wild appearance, the river does not flow freely; it is regulated by the upstream Glen Canyon Dam, which profoundly affects the surrounding natural environment and visitor experiences. The National Park Service and its partners in the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program are working on a 20-year experimental project to restore some of the natural systems that were damaged or lost because of the dam. The program is administered by the Bureau of Reclamation. The project covers 296 miles of the Colorado River, from Glen Canyon Dam at Lake Powell Reservoir through the Grand Canyon to Pearce Ferry at Lake Mead Reservoir. Scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey lead the program’s experiments, some of which have already proved fruitful.

Image credit: NPS / Mike Makowski

A Changed Ecosystem

Since its completion in 1963, the dam has changed downstream habitats along the river, adversely affecting some of them. Before the dam was built, sparsely vegetated sandbars along the Colorado River were more prevalent. River rafters and other backcountry adventurers valued these sandy beaches as campsites and break spots. Dam operations changed the river flow regime, decreasing the size and duration of large floods while also increasing the level of low flows. This caused native clonal plant species like arrowweed and non-native species such as tamarisk to encroach on sandbars, decreasing the size of campsite areas and degrading their condition. The previous occasional and high-quality bird habitats of cottonwood and willow gallery forests are now essentially nonexistent. This is because the regulated flows don’t allow for marsh back channels, which relied on periodic large floods.

The dam has also affected archeological sites. Many of these sites are in pre-dam river sediment deposits, which provide a protective barrier against erosion. The dammed river now carries up to 95 percent less sediment, which means there is less sand available to cover the fragile sites. Sites are commonly in sand dunes along the river corridor, where wind re-supplies the dunes with sand blown from adjacent sandbars. Encroaching vegetation on the sandbars limits movement of what little sand is now available to cover and protect these sites.

In 2018, the National Park Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and some of their partners began experimental vegetation treatments along the Colorado River below Glen Canyon Dam. This was in accordance with the 2016 Glen Canyon Dam Long-Term Experimental and Management Plan. Their purpose was to determine effective ways to mitigate the dam’s adverse impacts. The treatments have had some notable successes in improving the condition of campsites, archeological sites, and the riparian plant ecosystem.

Image credit: U.S. Geological Survey / Joel Sankey

Wind and Sand Preserve History

People have visited the Colorado River in Grand Canyon and Glen Canyon for at least 12,000 years. Indigenous and Native peoples have inhabited the region intermittently throughout that time. European explorers first visited the canyon 480 years ago. Hundreds of archeological sites along the river display evidence of those humans and their activities. Sites include masonry dwellings, ditches, agricultural fields, seasonal campsites, petroglyphs, roasting pits, and quarries. Other examples are remains of cabins, ferry boat crossings, mining locations, cowboy camps, and river-runner camps. Many of these sites occur on river terraces, debris fans, and other river channel margin deposits. They are now buried in dune fields made of windblown river sand deposited on top of those other landform types.

Image credit: NPS

The Colorado River has sandbars that occur throughout the canyon in consistent locations. River rapids generally occur at the confluences of side-canyon tributaries that constrict the mainstem river channel with debris fans. Historic river floods also created large terrace deposits in pre-dam times. As long as the river has existed, the wind has blown sand from the sandbars onto adjacent debris fans and terraces. The side-canyon tributaries often mark routes used by people to travel in and out of the Grand Canyon. Many river corridor archeological sites are found at the nexus of these different landforms and processes.

Owing to dam operations, few archeological sites are ever directly flooded by the river today, but wind still blows sand from adjacent sandbars onto riparian archeological sites. Regulated flood releases from Glen Canyon Dam intended to rebuild sandbars also increase the supply of windblown sand to adjacent dune field archeological sites. But when plants such as arrowweed or tamarisk colonize and expand across the sandbars, they shut down this process. The National Park Service and the U.S. Geological Survey are investigating how removing the plants on the sandbars affects downwind archeological sites. Their ambitious objective is to test whether vegetation management can improve sandbar campsites while also keeping downwind archeological sites buried by a protective cover of windblown sand.

"Many of our participants experience these majestic places for the first time through our program."

Image credit: NPS / Lonnie Pilkington

Five locations were selected for the initial study. Each has a sandbar overgrown with woody riparian plants and a downwind archeological site known to be buried in windblown river sand. The U.S. Geological Survey has also been monitoring the coupled sandbar and archeological site locations long term. This will help in evaluating the effectiveness of the restoration experiments.

Since spring 2019, the National Park Service has visited each of the five sites yearly to remove vegetation manually. The sandbar vegetation removal is intended to increase the area for river runners to camp while allowing for windblown sand transport. To minimize undesirable impacts, the crews do not work within the archeological sites, nor do they remove vegetation from them; plants on the sites can help capture sand. Following vegetation removal, the U.S. Geological Survey analyzes the project areas for changes in topography, sediment, and vegetation. The experimental management study is still underway. But at Basalt camp, one of the study locations, LIDAR analysis confirmed there is more windblown sand building up on the sandbar campsite and on the downwind archeological sites than before vegetation removal. This will improve the condition of both types of sites.

With the help of crews of Native American youth from Tribes in the Grand Canyon region, the park has removed invasive plants from Basalt camp each year since 2019. Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps and Arizona Conservation Corps staff the crews. “Many of our participants experience these majestic places for the first time through our program, and they learn important professional development skills,” said Ancestral Lands Conservation Corps Director Chas Robles. “The work they do to heal the landscapes their ancestors managed for generations also contributes to their own healing and the healing of our communities and helps them continue the legacy left to them as caretakers of the lands, waters, and air.”

Image credit: NPS / Gerry Nealon

Curbing Gargantuan Grass

You may have received an informal introduction to Ravenna grass while parking your car near a landscaped island at your favorite strip mall. Maybe your first thought was, “Wow! That grass is huge and oddly out of place.” If so, you are correct. As with many invasive species, people introduced and spread Ravenna grass, a native of Eurasia, in the desert southwest. In the 1970s, Ravenna grass appeared near Lake Powell and Glen Canyon Dam in Page, Arizona. Since then, it has colonized riparian areas along the Colorado River within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Grand Canyon National Park.

The Colorado River riparian zone provides ideal conditions for Ravenna grass spread and establishment, with each seed head capable of producing 10,000 seeds dispersed by wind and water. Over the years, controlling Ravenna grass, considered a noxious weed in several U.S. states, has been a high priority for both parks. Between 2017 and 2018, research within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area showed that Ravenna grass declined after herbicide treatment and manual removal, but returned several months later. Manual and chemical treatments have been successful when done annually and repeatedly, enlisting the help of partners.

"We started to see Ravenna grass take over entire beaches along the Colorado River in Grand Canyon even as early as the mid-1990s. We would kill over 10,000 plants in a single trip."

In the desert southwest, longtime Grand Canyon river rafting guide Dan Hall and Ravenna grass are often mentioned in the same breath. Hall has spent 28 years looking for and treating Ravenna grass along the Colorado River. “As river guides, we started to see Ravenna grass take over entire beaches along the Colorado River in Grand Canyon even as early as the mid-1990s,” he said. “We would kill over 10,000 plants in a single trip. Many of us were trained by National Park Service personnel to recognize and effectively treat the grass by digging it out. Over the decades, that cooperative effort between the park and the guiding community has gotten us to a point where spotting any Ravenna grass in Grand Canyon is rare.”

Image credit: NPS / D. Boughter

The Challenge of Restoring Cardenas Marsh

Federally endangered southwestern willow flycatcher populations have declined in recent decades along the Colorado and other rivers in the desert southwest. This is because their riparian habitat has been lost or degraded, and non-native plants, including tamarisk, have invaded the area. Flycatchers have shifted their habitat preference from willow and cottonwood gallery forests to tamarisk-dominated stands. But the northern tamarisk beetle is now defoliating these same stands, leaving flycatchers in “habitat limbo.” Cardenas camp is a popular site to spend the night for both river rafters and backpackers. The area surrounding the campsite has unique features, including a densely forested riparian marsh and cultural sites like the Cardenas (hilltop) site. Restoring sites like the riparian marsh at Cardenas will allow willow flycatchers and other species that depend on riparian habitat to nest in native vegetation that is unaffected by the tamarisk leaf beetle.

Grand Canyon National Park intentionally designed the Cardenas restoration project to improve southwestern willow flycatcher habitat. Park staff documented all plant species identified within the project area and developed a restoration plan for the site. Then they removed dead and dying tamarisk and planted native species such as young Fremont cottonwood and Goodding’s willow. They caged the plants to protect them from American beavers and developed monitoring and watering schedules. The Cardenas site proved very challenging to restore, but the park learned many useful lessons along the way.

One group of volunteers called for helicopter rescue before even reaching the site.

The site is difficult to access, requiring a 12-mile hike from the canyon rim or a multi-day river trip. Extreme heat prevents park personnel from safely hiking to the site from May through September, which is when the park employs seasonal staff. The site was thus accessed primarily by river. Initially, the park removed tamarisk by cutting existing plants and disposing of cut material in the river, followed by herbicide treatment of resprouts. Unpublished data show that this approach worked well; over half of the tamarisk stumps did not resprout, and a smaller amount of herbicide treatment was required than if every cut stump was treated with herbicide.

Most importantly, watering the cottonwoods and willows needs to be consistent, especially during the hot summer months, to get plants established. Once the park completed replanting the site, it partnered with the Backcountry Information Center to add language to hiking permits to recruit volunteers to help with site watering. But that presented its own challenges: one group of volunteers called for helicopter rescue before even reaching the site. The park subsequently decided that it could not use volunteer backpackers for site watering.

The park hopes to collaborate with other groups such as Grand Canyon River Guides and Grand Canyon Youth to increase the success of this and other restoration projects on the river. "Stewardship is all about giving back to a place you love,” said Grand Canyon River Guides Director Lynn Hamilton. “As a nonprofit organization, it is so gratifying to be able to partner with the National Park Service, working together towards a common goal for the betterment of the recreational resource we all depend upon." Grand Canyon Youth Director Emma Wharton said, "Grand Canyon Youth is so grateful to have our participants included in the vegetation work at Grand Canyon National Park. These projects help them learn both about the threats of invasive species and about the great work scientists and land managers are doing to mitigate these impacts."

Future plans for the Cardenas site include controlling invasive plants, planting additional native riparian plants, and monitoring to evaluate success. The park also plans to monitor and evaluate planted tree survival, growth, and success of seeding for upland species at Cardenas marsh. It will use groundwater wells to monitor the water throughout the growing season and ensure plants are planted deep enough to access water.

Image credit: NPS / Taryn Preston

Lunch Beach Gets a Makeover

Lunch Beach is a day-use area along the Colorado River in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. It is located approximately halfway between Glen Canyon Dam and Lees Ferry, Arizona. It's a popular stop for kayakers and boaters to take a break from the sun and wind. Until recently, it was characterized by a long, dense, unattractive stand of mostly dead or dying tamarisk trees. The area is in a unique reach of the river with a well-developed, pre-dam, high-water vegetation zone on the upper terrace. It has stands of native plants like desert olive, hoptree, live oak, and netleaf hackberry.

The park coordinated with other land management agencies, Tribes, Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center, and the Bureau of Reclamation to select this site. Selection was based on ecological, recreational, and archeological conditions. When the park assessed the site, it determined that the dead and dying tamarisk trees needed to be cut down and live tamarisk trees treated with herbicide. Something also had to be done with the large amount of cut and treated trees. Burning that biomass at the site, which is a common riparian restoration practice, could damage wetland vegetation and upslope desert vegetation. Instead, the park decided to haul the wood out by boat so that local Navajo residents could use it for firewood.

As the year went on, the crews collected more and more wood, totaling 17 cords, about as much volume as 16 thousand gallons of water.

Image credit: NPS / Taryn Preston

Youth Conservation Corps crews worked with park staff at the site in the fall of 2018 to begin clearing the area of tamarisk. Park staff and licensed crew members treated live tamarisk trees with herbicide to limit future regrowth. In 2019, youth conservation crews, interns, volunteers, and park staff worked to clear woody debris from the restoration site. They broke up small woody debris and put it through a chipper for spreading out at the site. They cut larger woody debris into firewood-sized chunks and put it into piles.

As the year went on, the crews collected more and more wood, totaling 17 cords, about as much volume as 16 thousand gallons of water! In late 2019, crews completed the removal of the larger diameter trees and readied the piles for transport. The park used one of its boats to haul the 17 cords of wood 12 miles downriver to the Lees Ferry boat ramp, where it was unloaded and stacked for free use by local residents. Another conservation crew planted 35 rooted coyote willow poles and 158 potted seepwillows, which have established and are growing well.

Once again, partnerships served as the backbone of the project. A cooperative agreement between the National Park Service and Page Unified School District in Arizona facilitated propagating coyote willow and seepwillow at the Page High School greenhouse. The park plans to plant more native vegetation as the restoration project progresses.

Image credit: NPS / Taryn Preston

Fulfilling the Grand Canyon Protection Act

The impact of this project has not gone unnoticed: visitors have seen the increase in camping spaces along critical sections of the river corridor and witnessed the enhanced wildlife habitat at Cardenas marsh. National Park Service Colorado River coordinator Rob Billerbeck has helped to administer the experimental vegetation treatments along the Colorado River since their inception. “This vegetation restoration project along the Colorado is one of the best examples of the Bureau of Reclamation really fulfilling the intent of the 1992 Grand Canyon Protection Act's mandate to protect, mitigate adverse effects to, and improve the resources downstream of the Glen Canyon Dam,” said Billerbeck. “The National Park Service is greatly appreciative to the bureau, to the states, to our Tribal partners and the other members of the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program for funding this great work.“

About the authors

Lonnie H. Pilkington is the vegetation program manager for the Science & Resource Management Division at Grand Canyon National Park.

Image courtesy of Lonnie Pilkington

Joel B. Sankey is a research geologist at the USGS Southwest Biological Science Center and Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center.

Image courtesy of Joel Sankey

Daniel L. Boughter is a vegetation biologist and the hazard tree program coordinator for the Science & Resource Management Division at Grand Canyon National Park.

Image credit: NPS

Taryn N. Preston is the acting chief of science and resource management at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Rainbow Bridge National Monument.

Image credit: NPS / S. Preston

Cam C. Prophet is the invasive plants crew lead for the Science and Resource Management Division at Grand Canyon National Park.

Image credit: NPS / Cam Prophet