Last updated: June 1, 2022

Article

Thaddeus Bell and James Etheredge: Changing Expectations

In the mid-1960s James Etheredge and Thaddeus Bell joined a cohort of young African American men that the Department of the Interior recruited in an effort to diversify the workforce. The National Park Service assigned them to parks in the West, a region where most employees were white. Etheredge and Bell had seldom recalled the summer seasonal jobs until 2019, when they met NPS rangers and managers at an African American history conference in Charleston, South Carolina. To their surprise, they learned that they had helped to blaze a trail for African American employees and that their stories mattered. What were their experiences like? To find out, in 2021 Dr. Lu Ann Jones, Oral History Coordinator for the NPS Park History Program, collaborated with Dr. James Harper, Chair of the Department of History at North Carolina Central University, to record oral history interviews. Mr. Etheredge illustrated the conversation with photos he had taken to record his experiences.

Courtesy of James Etheredge

From Campus to Park

Bell and Etheredge were students at South Carolina State College when Interior department representatives made a recruiting trip to campus searching for NPS seasonal rangers.

“I didn’t know what the National Park Service was,” said Bell. He was assigned to Yosemite National Park in California. “I had never heard of Yosemite National Park. I had never been outside of the state of South Carolina. The mere fact that I was going to be going to work in Yosemite National Park for three months during the summer – I was just blown away by that.”

Etheredge remembered, “I was aware of the park system only by name, but not certainly by knowledge. When I got the appointment to Grand Canyon National Park, then I started to do some research on that. I was just smitten, I just said yes, this is what I want to do. I really want to do that. So that’s the way it started.”

Bell and Etheredge headed west at a time of tumultuous social and political change. As undergraduates they had participated in civil rights protests firsthand. Now they were closer to the youth counterculture and racial reckonings in big cities like Los Angeles, where the Watts neighborhood exploded in the summer of 1965 over police abuse of African Americans.

Heading West

Courtesy of James Etheredge

The young men traveled when lodging and restaurants could still be segregated, by custom if not by law. Harassment by white people was always a possibility. Etheredge hitched a ride to the Grand Canyon with friends who were headed to California for their honeymoon. During the two-day trip, the travelers took turns driving and stopped only for gas and food. “It was a grueling trip,” Etheredge remembered.

Bell took a train from Columbia, South Carolina to Los Angeles, and then a bus to Yosemite. The trip took five days because detours around flooded tracks created delays. Bell recalled staying well-fed during the long trip because his mother had fried lots of chicken and packed enough sandwiches to last several days. He laughed, “I saw a lot of America riding on the train.”

Getting Acquainted

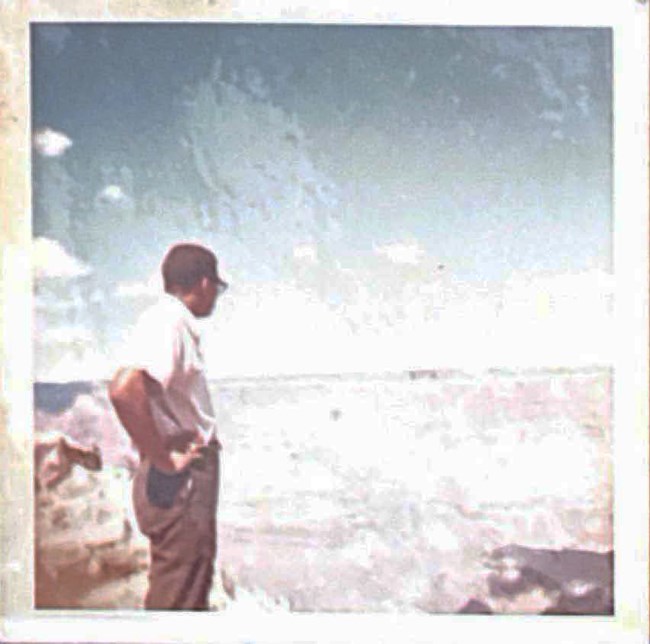

As Bell and Etheredge met co-workers and got oriented to their new positions, they also took in the magnitude and majesty of their scenic surroundings.

Etheredge recalled his first impression of the Grand Canyon.

-

James Etheredge: Arrival at the Grand Canyon

In an oral history interview with the Park History Program, James Etheredge shares his first impression of the enormity of the Grand Canyon.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS Park History Program

- Date created:

- 04/06/2022

Bell took advantage of Yosemite’s varied and rugged terrain. But it was hard to hide that he was a novice in the West’s big mountains.

-

Thaddeus Bell: Introduction to Yosemite

In an oral history interview with the Park History Program, Thaddeus Bell describes his first impression of Yosemite National Park and some of the initial learning experiences

- Credit / Author:

- NPS Park History Program

- Date created:

- 04/06/2022

These new positions in unfamiliar places provided opportunities for both awe and adjustment. The weather, the food, the people were different than South Carolina. But Bell and Etheredge didn’t arrive completely empty-handed and unprepared.

Showing Up to the Job

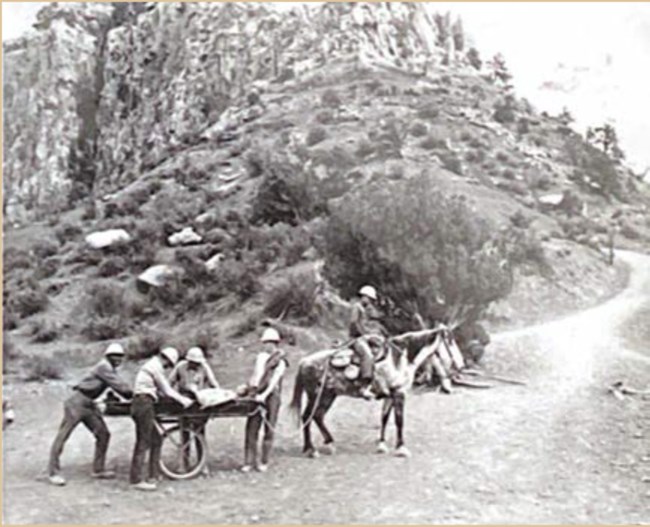

Courtesy of James Etheredge

While Bell and Etheredge came to their positions with no experience with the NPS or in the West, they came equipped with other skills that proved useful.

A physical education major, Etheredge was in good shape, a factor he assumes contributed to his selection. He also had an even temperament, “a personality to be able to cope [in an] unfamiliar environment,” a plus in a situation where racism might rear its ugly head. Returning for a second season, this time with his new bride, he staffed an entrance station and did campground patrols. He also helped with search and rescue and fire suppression. Plus, Etheredge introduced a new item to the Grand Canyon general store. When he could not find grits on the shelves, he convinced the manager to stock the southern food favorite.

After working Yosemite’s Arch Rock Entrance Station the first season, Bell enjoyed a promotion to radio dispatcher during his second summer. The position put him in the middle of the action; he knew what was going on all over the park and was responsible for directing cars and rangers to accidents or emergencies. “I was right there, the person who was making it happen,” Bell said. “So I thoroughly, thoroughly enjoyed that. As a result, I made friends from people all over the park.” During his third summer at Yosemite, Bell was entrusted with a horse; on his patrols he visited with and assisted park visitors.

-

Thaddeus Bell: "It fit my personality just fine"

In an oral history interview with the Park History Program, Thaddeus Bell describes his third summer at Yosemite National Park, assisting and interacting with visitors while riding through the park on horseback.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS Park History Program

- Date created:

- 05/03/2022

Courtesy of Thaddeus Bell

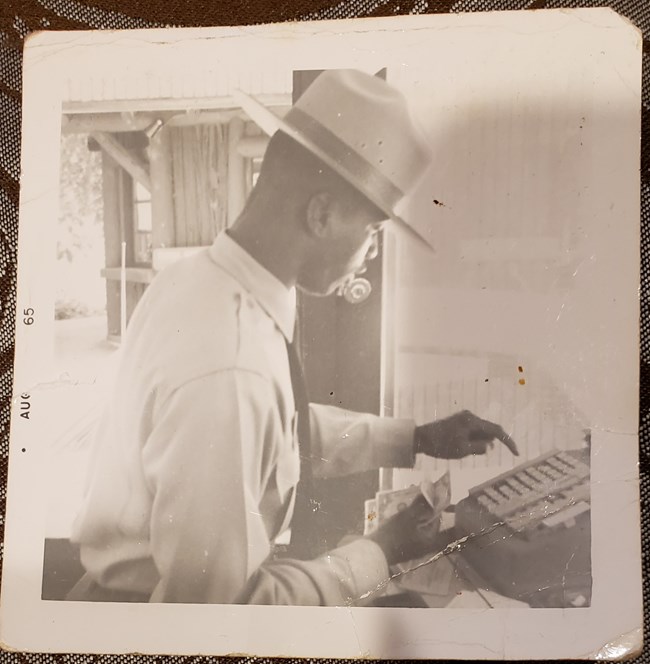

Dressing the Part

Bell and Etheredge were surprised at how much donning the iconic NPS ranger uniform and flat hat changed their perceptions of themselves and others’ perceptions of them.

Bell immediately felt the uniform’s symbolic power. “When I got that uniform, I wore it to church. I wore this big hat to church and the green uniform. And you know, people were so proud of me because what this represented. I said, ‘Hey, listen, I’m getting ready to go be a park ranger out at Yosemite National Park.’ So my family and friends, they just thought it was a great thing. And it was. It was.”

Etheredge still owns and preserves the ranger uniform he bought over half a century ago. He noted the status that the uniform and flat hat lent him in the eyes of the public at the Grand Canyon—people looked to him for help.

-

James Etheredge: Wearing the NPS Uniform

James Etheredge talks about his experience wearing the NPS uniform at Grand Canyon National Park.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS Park History Program

- Date created:

- 04/07/2022

Interactions

Bell, Etheredge, and the few other African American men who became rangers at that time formed a vanguard in the NPS, joining an overwhelmingly white workforce who, as Bell said, “were surprised to see a Black ranger.” Differences could inspire education—and friendship. For example, Bell described going for a haircut in a shop where all the barbers were white. Lesson followed lesson.

-

Thaddeus Bell: New Friends, New Lessons

During an oral history interview, Thaddeus Bell shares a story of a friendship that developed from a haircut at Yosemite National Park and the learning that followed from differences.

- Date created:

- 05/04/2022

Racial discrimination was not unknown, but Etheredge found NPS co-workers to be cordial and respectful.

-

James Etheredge: NPS Co-Workers

James Etheredge recalls interactions with his NPS co-workers and visitors during an oral history interview with the Park History Program.

- Credit / Author:

- NPS Park History Program

- Date created:

- 05/04/2022

After the National Park Service

Neither Bell nor Etheredge pursued a career with the National Park Service. They both returned to South Carolina and continued to make important contributions to their communities, professions, and civic organizations.

Etheredge counted a number of firsts: first physical education coordinator for the Rock Hill School District; first African American Head Start director in the Rock Hill area; first African American to earn a master’s degree in public administration at the University of South Carolina. Etheredge spent most of his career serving as the comptroller for the City of Charleston. After he retired in 2000, he began another job as a payroll analyst for the Department of State.

Bell considered staying with the NPS, but his wife wanted to return to South Carolina. He taught high school until in 1976; after several attempts, he gained admission to the previously all-white Medical University of South Carolina. The discrimination he encountered there encouraged him to dedicate his career to treating underserved minority communities and addressing racial disparities in health care.

Eventually, the medical school invited Bell to join its faculty and develop programs that would increase minority enrollment and the number of African American doctors in practice. He initiated Closing the Gap in Healthcare, which dispelled myths and misinformation surrounding African American health care and encouraged better health practices.

Courtesy of James Etheredge and Thaddeus Bell

Lasting Impacts

With openness to the unfamiliar, James Etheredge and Thaddeus Bell shaped and were shaped by the people, places, and interactions in the NPS. Their few seasons at Yosemite and the Grand Canyon were significant steps in starting to change expectations about who belongs in the “green and gray.”

“When I left the Grand Canyon,” Etheredge reflected, “I knew that the Grand Canyon community had an experience with a Black guy. So hopefully that was the first point in the building of that openness and diversity.”