Part of a series of articles titled NRCA 2022: Condition of Glen Canyon's Tributary Rivers and Associated Resources.

Article

Condition of Glen Canyon's Tributary Rivers and Associated Resources: Natural Resource Assessment 2022

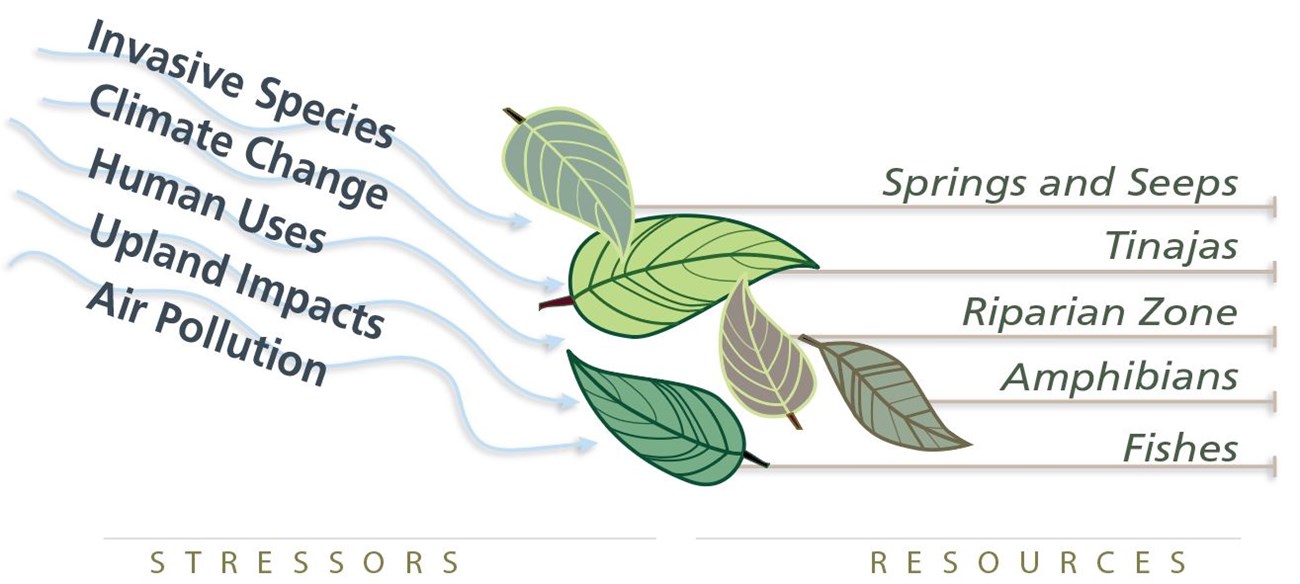

Ecosystem drivers and stressors: What is causing change in resource conditions?

An important part of the NRCA is identifying the primary threats and stressors affecting the condition of the selected natural resources. Understanding what forces are driving changes in conditions can help a park prioritize stewardship activities. Historically, the NPS has sought to maintain natural resources in the historical or “pristine” condition, but ecosystems evolve and adapt to large-scale changes, and park ecosystems will change as well.

Focusing in on a set of natural resources in Glen Canyon

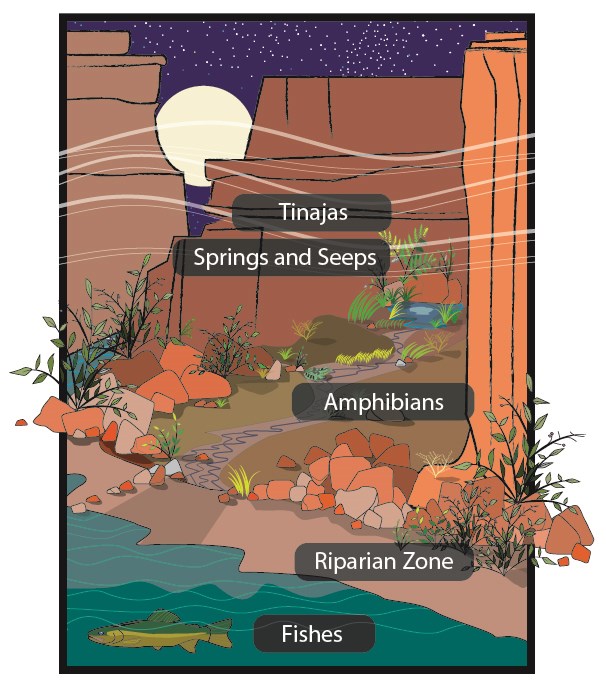

Studies of natural resources in Glen Canyon often focus on Lake Powell and the Colorado River. For this NRCA, often overlooked resources associated with tributary rivers and smaller water sources were selected as focal resources. Focal resources found to have little existing information were not excluded; instead, they were the focus of a data gap analysis rather than a pure condition assessment.

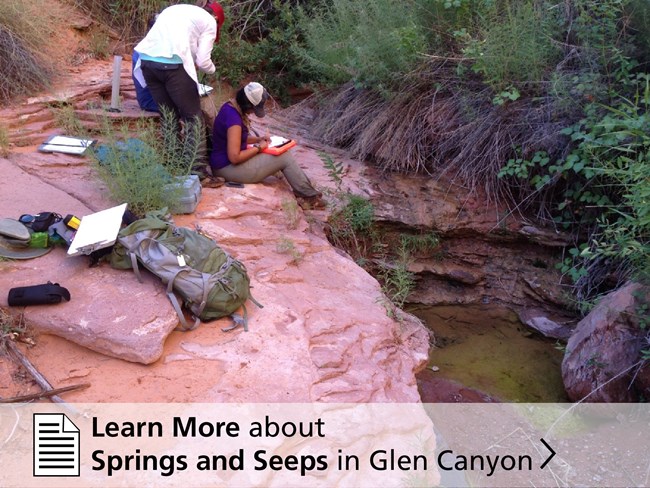

Springs and Seeps

Springs and seeps connect groundwater to the surface, providing an important source of water to plants and animals throughout the desert. One particular type of spring, called a hanging garden, is a hotspot of biodiversity and home to rare plants. In fact, these lush hanging garden alcoves are so large and prominent at Glen Canyon that the park was named after them.

NPS Photo

Fishes

Nearly one-half of all known fish species across the globe live in fresh water. This means they live in rivers, wetlands, and lakes, including those in Glen Canyon. Twenty-six fish species occur in Glen Canyon NRA, but only eight of them are native.

US Fish and Wildlife Service/Sam Stukel

This second group of four native species has been less studied than other fishes in the region and was one area of focus in our assessment. We found that none of the four rivers where the fishes occur have significant impacts to water quality, although information is lacking for some types of contaminants. We also found that in the upper Escalante River, all four fish species were consistently present and their populations appeared stable. However, in the lower Escalante and San Juan rivers, some of the fish species were absent or severely reduced and dominated by non-native species.

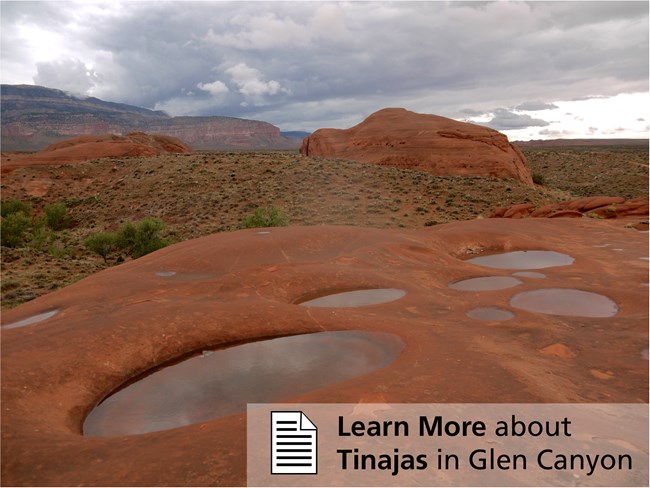

Tinajas

Tinajas (also called waterpockets and pools) are depressions eroded in the sandstone bedrock that hold water from precipitation and snowmelt. While smaller tinajas tend to dry out, larger tinajas can retain water year-round and support riparian plants.

NPS Photo

Tinajas are common throughout Glen Canyon NRA, and they are especially prevalent in the Waterpocket Fold area of the park. This study mapped over 300 square miles of potential tinajas in Glen Canyon. We know tinajas are important, but there have been few studies on this resource. Drought and warming temperatures are the primary stressors for tinajas, increasing evaporation and decreasing how long water persists in pools.

Amphibians: featuring the Northern Leopard Frog

Amphibians, including frogs, toads, and salamanders, primarily reproduce and develop in aquatic habitats, although some spend much of their time (as adults) in drier environments.

US Fish and Wildlife Service/Sam Stukel

At Glen Canyon NRA, the current status of amphibians as a group is unknown due to a lack of information. More, however, is known about northern leopard frogs. This species was more prevalent before Lake Powell filled, but now these frogs live in fewer locations that are more isolated from one another. Of 29 locations that used to contain northern leopard frogs, only four currently do and eight others may (but this is not known for sure). Good news, however, is that the species is breeding in the known locations, and of frogs that have been tested for a serious amphibian disease (chytridiomycosis), none have tested positive.

Riparian Zone

Glen Canyon has over 3,000 miles of waterways that provide riparian habitat along rivers and streams. Riparian plants shade streams and keep water temperatures cooler for fish and provide habitat for a multitude of other wildlife and insect species. This study evaluated water availability, stream health, and vegetation for seven streams and rivers in Glen Canyon: the Dirty Devil, Escalante River, Halls Creek, Lake Canyon, Coyote Gulch, Harris Wash, and the San Juan River.

NPS Photo

April and May stream flows on the Escalante River decreased from 1943 to 2020. But all of the river within Glen Canyon is downstream of the stream gage, and we don’t know if stream flows have decreased there as well, since there are numerous springs that feed the lower Escalante River. There were no impairments to water quality in the seven streams, and aquatic intactness was rated as high or moderately high at 78% of watersheds on these streams. The condition of vegetation along streams is poor, mostly due to invasive exotic species. The NPS and partners work hard to remove exotic plants, but the proliferation of tamarisk, Russian olive, ravenna grass, and other species present an ongoing management challenge.

Using what we learned to take action

Knowing the condition of these resources and what information is missing is only the first step. We also need to link our findings to actions park managers can take to better protect the resources in their park. A critical part of any NRCA project is a manager-scientist discussion to identify how the park can use this information to prioritize stewardship actions, guide future monitoring activities, and select important next steps. Here are some things that we learned.- Multiple stressors affect each resource and drive changes that make it challenging for the park to protect them.

- Warming temperatures and increasing frequency and intensity of droughts affect the hydrology or the habitat of all of the resources evaluated in this study.

- Park managers identified their greatest need as acquiring additional information through research, monitoring, and inventories. One example of this is the need to better understand how increasing temperatures will affect the hydrology of springs and seeps, tinajas, and riparian areas.

- Our findings help land managers make the most informed decisions about where to spend their limited budgets on treatments like restoration of habitat or species, fencing to exclude livestock, or exotic plant removal.

- Park managers acknowledged the importance of partnerships, such as the Escalante River Watershed Partnership, for addressing larger-scale resource issues and stressors.

- Park managers identified many visitor education and visitor use planning strategies to effectively protect resources.

You too can be part of the solution!

Visitors to Glen Canyon play an important part in protecting natural resources. Tinajas and hanging gardens, for example, are popular destinations and serve as an important source of water for backcountry visitors. Understand what you can do to maintain water quality, protect fragile vegetation and wildlife habitat, and prevent fires in vulnerable locations. Learn more about how you can protect each of these resources in our articles about spring and seeps, fishes, tinajas, amphibians, and riparian zones at Glen Canyon.

Information in this article was summarized from: Albright J and Others. 2022. Natural resource conditions at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area: Findings & management considerations for selected resources. Natural Resource Report. NPS/SCPN/NRR—2022/2374. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2293112

Last updated: July 14, 2022