Part of a series of articles titled NRCA 2022: Condition of Selected Natural Resources at Capitol Reef.

Article

What do a Tadpole Shrimp and a Mule Deer Have in Common? They Both Rely on the Water Resources of Capitol Reef

The importance of these waters

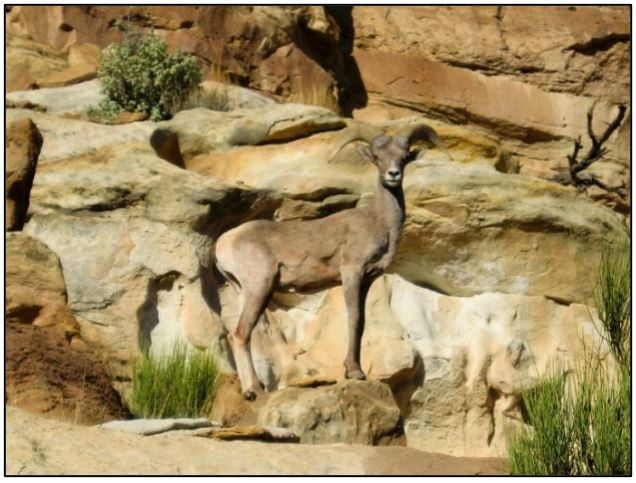

Springs, seeps, and tinajas support a host of endemic plants (those found in a particular region and nowhere else), terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates, and amphibians. They may also supply water to streams. Many mammals, including desert bighorn sheep and mule deer, and breeding and migratory birds also depend on these resources for the water and habitat they provide. Springs in Capitol Reef, which are points of groundwater discharge, may serve as a refuge for organisms as temperatures rise and surface water becomes less available due to climate change.

In the southwestern U.S., riparian areas along streams and rivers make up only a small percentage of the land area, but they support a very high diversity and abundance of plants and animals compared to other habitat types in the region. In addition to providing habitat, riparian plants along streams add to the diversity and complexity of the floodplain, stabilize stream banks, and provide shade, which reduces stream temperatures and provides cover for fish and other aquatic species.

See Water in the Desert on Capitol Reef’s website for more information.

What threatens these resources?

The water resources at Capitol Reef NP can be negatively affected by a variety of factors, including:

- Non-native invasive plants that can outcompete native species. Some non-natives, such as tamarisk, also use a lot of water.

- Pollutants from the atmosphere (such as heavy metals) or runoff (such as nitrogen fertilizers, E. coli bacteria) that can contaminate water.

- Decreases in groundwater, from a lower snowpack, changes in precipitation, or pumping of groundwater, that reduce the amount of water that springs produce.

- Drier and warmer conditions associated with climate change that affect the amount and persistence of water in springs and tinajas, as well as streams. These conditions also stress native plants.

Assessing condition of water resources at Capitol Reef

A recent Natural Resource Condition Assessment (NRCA) through the NPS NRCA Program focused on a number of resources in Capitol Reef NP, including springs, seeps, and tinajas, and riparian areas along perennial streams. NRCAs evaluate natural resource conditions so that parks can use the best available science to manage their resources.

Ecologists at Utah State University (USU): synthesized the available information on springs, seeps, tinajas, and riparian areas; pointed out data gaps; and recommended indicators of condition for future condition assessments.

Here is some of what we learned

NPS Photo

- The study found that there could be as many as 170 springs and seeps in Capitol Reef.

- A past study of more than 400 tinajas in the park found that the largest tinaja, if full, could hold about 405,000 gallons of water—that’s roughly two-thirds of an Olympic-sized swimming pool! But most tinajas hold 3,965 gallons (about 95 full bathtubs) of water or less.

- More than 50 macroinvertebrate species have been recorded in the park’s tinajas, including two species of fairy shrimp, pond snails, and many different insects.

- Because tinaja locations were only partially mapped in Capitol Reef, USU ecologists, using an NPS geology database, identified park areas that are likely to contain tinajas; they found 35% of the park has the potential to support tinajas (throughout the entire park, north to south).

What can park managers do with this information?

Information from the study can be used to inform park planning and management actions that involve these water resources and the animals and plants that depend on them.

NPS/Jane Gamble

- Implement a springs and groundwater study to understand surface-groundwater interactions and to determine where streams are gaining or losing groundwater across geologic formations. The study would include a field inventory to verify spring/seep locations and types and selecting a subset of springs/seeps for long-term monitoring of water quality and quantity.

- Delineate tinajas using LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing method), which could identify tinajas quickly and accurately over large areas of the park.

- Identify streamflow needs and monitor contaminants, including mercury levels, for native fish.

|

What You Can Do to help protect Capitol Reef’s water resources

|

|

|

|

|

Information in this article was summarized from: Struthers K and Others. 2022. Natural resource conditions at Capitol Reef National Park: Findings & management considerations for selected resources. Natural Resource Report. NPS/NCPN/NRR—2022/2406. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2293700

Last updated: July 14, 2022