Part of a series of articles titled NRCA 2022: Condition of Selected Natural Resources at Capitol Reef.

Article

Condition of Selected Natural Resources at Capitol Reef: 2022 Assessment

NPS photo

Understanding the condition of our natural resources, as well as trends in condition (that is, are conditions improving, declining, or remaining stable), is vital for managing and protecting park resources. If we don’t collect information on these resources, how would we know that what we’re doing is working?

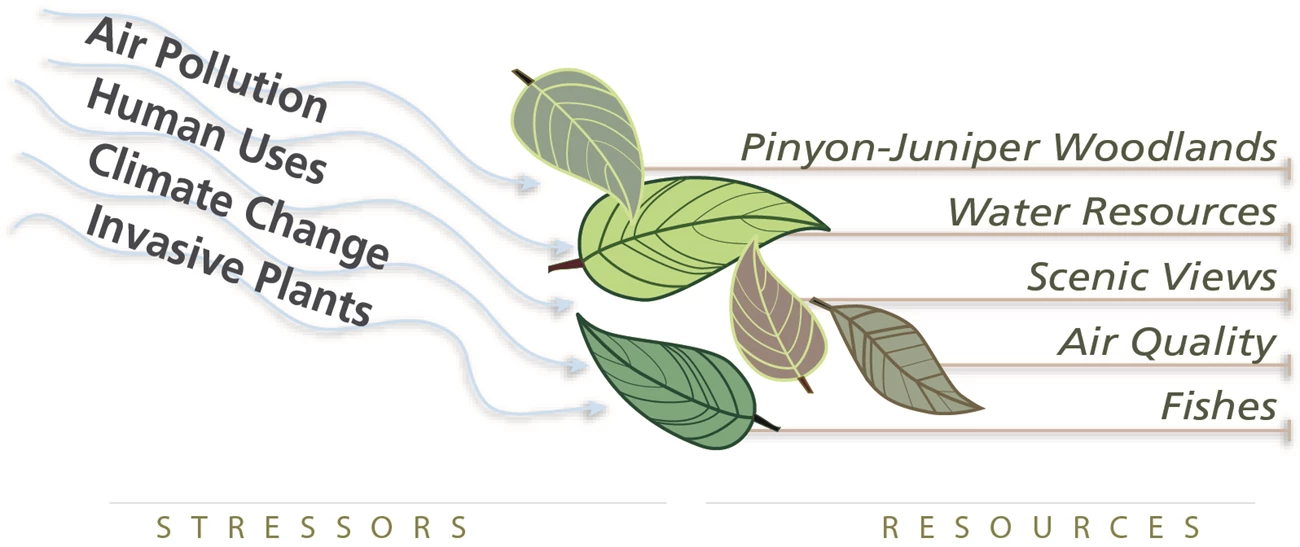

Ecosystem drivers and stressors: What is causing change in resource conditions?

An important part of the NRCA is identifying the primary drivers and stressors affecting the condition of the selected natural resources. Understanding what forces are driving change in conditions can help a park determine needed management and stewardship activities.

Focusing in on a set of natural resources in Capitol Reef

Capitol Reef National Park (NP), in southcentral Utah, encompasses approximately 381 square miles, nearly all of which is managed for its rugged and remote wilderness value. The park is known for its spectacular display of geologic features, including an extensive, upthrusted sandstone geologic feature (the Waterpocket Fold) that is the longest exposed monocline in North America. Capitol Reef also hosts one of the largest concentrations of rare and endemic plants among national park units. The Fremont River and other perennial streams, and springs, seeps, and tinajas, are valued sources of water in the high desert environment of the Colorado Plateau, providing vital habitat for numerous animal species. At least 58 mammals, including desert bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis nelsoni), have been confirmed at the park, and a few native fish species are of special conservation status in Utah.Eleven resources were selected for this NRCA, but we focus on only a portion of them in this series of web articles. We evaluated the 11 resources as either a condition assessment (five of the resources) or a gap analysis (six of the resources), depending on data availability. A condition assessment is a more thorough evaluation of a resource’s current condition, and a gap analysis highlights what we do and don’t know about a resource and provides suggestions for collecting needed information for future assessments.

The 11 resources are listed here, with those in bold addressed in this article: night sky and air quality; soundscape; springs, seeps, and tinajas; streams (and their riparian areas); pinyon-juniper woodlands; grasslands and shrublands; rare plants; songbirds; Mexican spotted owl; desert bighorn sheep; and fish.

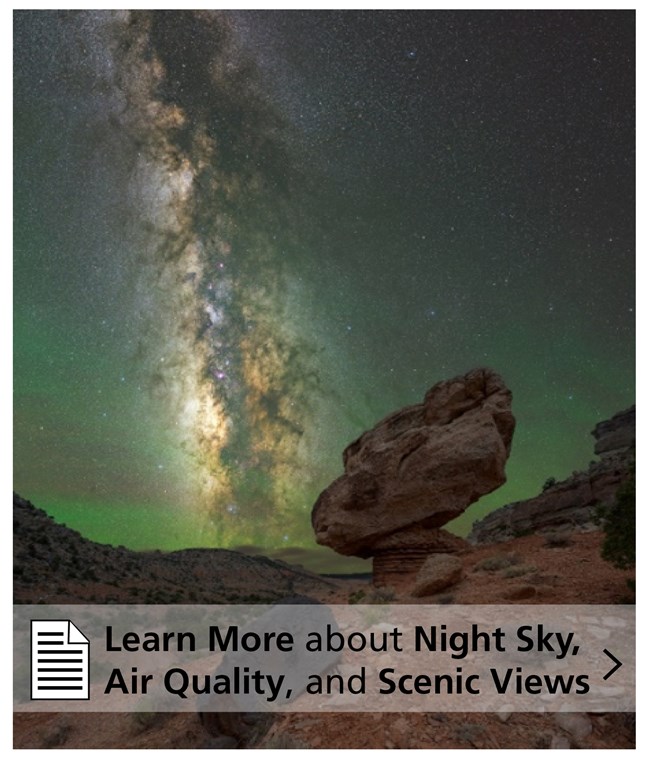

Night Sky, Air Quality, and Scenic Views

Some of the darkest night skies in the entire country can be seen in Capitol Reef NP. Capitol Reef is also a beautiful place during the day, with its colorful and impressive scenic views. Both dark night skies and scenic views, as well as air quality, are valuable resources protected by the NPS.

NPS/Phil Sisto

As part of our study, we assessed condition of the night sky using four indicators and condition of air quality using two indicators (daytime visibility and ozone). Based on the indicators, we found condition of the night sky is good, and condition of air quality is fair. In 2018, the measured visual range (how far you can see) at Capitol Reef was 86 to 179 miles. Without the effects of pollution, the estimated visual range would be farther—127 to 197 miles. Good news, however, is that air quality, and therefore visibility, will probably improve because the largest coal-fired power plant in the western U.S., south of the park, was decommissioned in 2019.

Soundscape

NPS/Ariel Solomon

Our study included results from a model, developed by the NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, that predicts the impact from noise levels. The model indicates a fair condition of the park-wide sound level, as well as fair conditions in the primitive and semi-primitive management zones of Capitol Reef (93% of the park’s area), and poor conditions in the remaining park zones, including the road corridor. Small areas, such as the road corridor (0.2% of the park), can have a large effect on soundscape quality. At the time of our assessment, park staff were also collecting acoustic data (continuous digital audio recordings) at three locations in the park. Once these data are analyzed, we’ll know even more about natural sounds and noise sources and levels.

Springs, Seeps, & Tinajas, and Streams

Springs, seeps, tinajas, and streams create unique habitats and are rare sources of water in Capitol Reef, which is located within a “high desert” region. There are only a handful of perennial streams that run through the park, while springs, seeps, and tinajas are scattered throughout. Wildlife, such as desert bighorn sheep, mule deer, breeding and migratory birds, and amphibians rely on these water resources. Tinajas even support invertebrate species that are specialized for a short life cycle in temporary pools of water.

NPS/Ann Huston

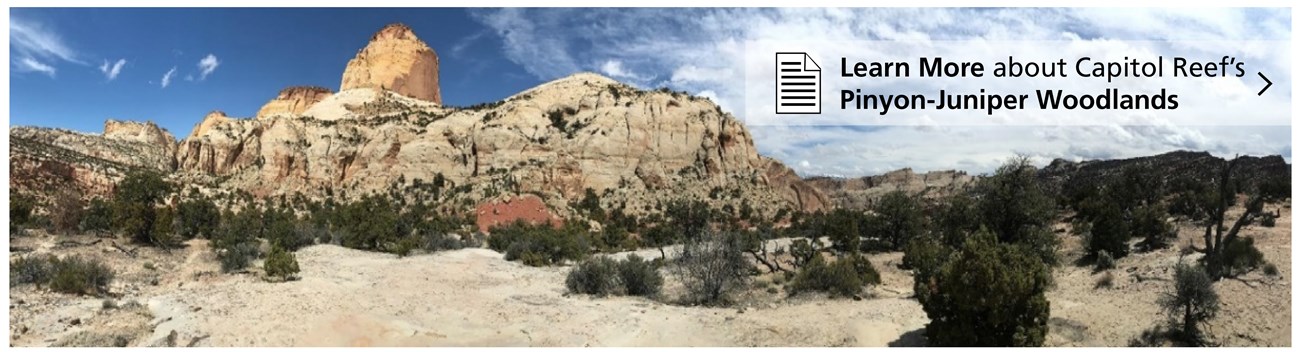

Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands

NPS/Shauna Cotrell

Our assessment found that conditions for tree density, age-class distribution, and songbirds are good, and crown cover increase is good/fair. We found that only a small portion of the park (less than 3.5%) has relatively dense pinyon-juniper woodlands. There is little evidence that they’re reaching a more closed condition with increased risk of wildfire or alteration of ecosystem services. The densest woodlands are located along the park’s western border in the far northern and central regions. For age-class distribution, we found that the majority of the pinyon-juniper woodlands in the park are in an open, early development condition and are likely to remain so for some time. Pinyon-juniper woodlands in the park also continue to support populations of two pinyon-juniper-dependent songbirds, pinyon jay and ash-throated flycatcher.

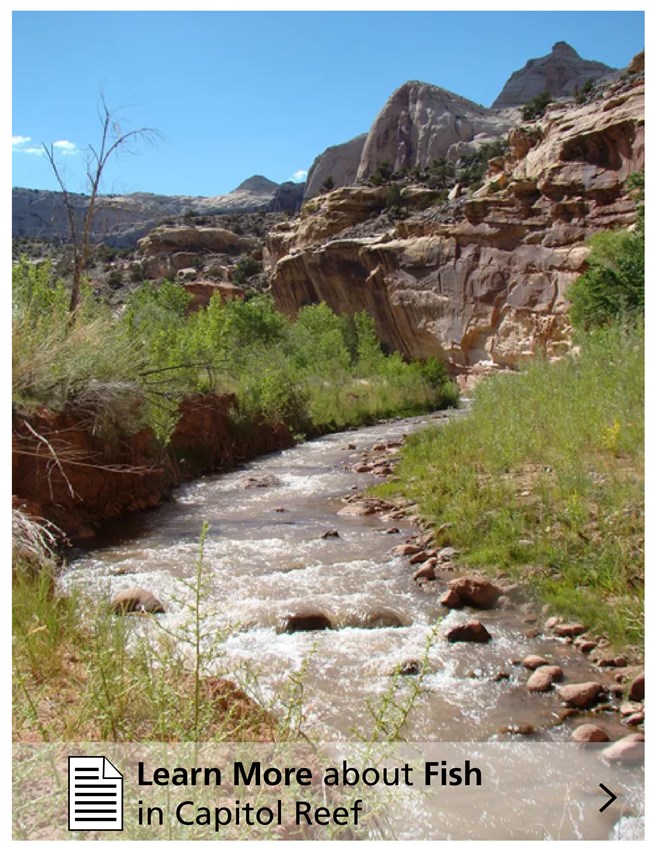

Fish

At least three native and eight non-native fish species are known to occur in Capitol Reef’s perennial streams. An additional native species, the roundtail chub, used to occur in the park.

NPS/Ann Huston

Our assessment of fish found that the biological community is in fair condition in the Fremont River, where most of the native species were consistently present but non-native fish were also recorded. Habitat quality for native fish is good/fair in the Fremont River, but it’s unknown in the other streams. Data suggest that water quality conditions (dissolved oxygen and temperature) were good/fair for the Fremont and the other streams, with temperatures sometimes elevated. Conditions with regards to contaminants were less favorable and rated as fair/poor. Most contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) searched for in water samples from the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek were not found, but seven CECs were found in the Fremont and three were found in Sulphur Creek.

Using what we learned to take action

Knowing the condition of these resources and what information is lacking is only the first step. We also need to link our findings to actions park managers can take to better protect the resources in their park. A critical part of any NRCA project is a manager-scientist discussion to identify how the park can use this information to prioritize stewardship actions, guide future monitoring activities, and select important next steps. The “next steps” may integrate multiple resources, park divisions, and/or partnerships. Here are a few of the things we learned at Capitol Reef.- Multiple stressors affect each resource and drive changes that can make resource protection challenging for the park.

- Warming temperatures and increasing frequency and intensity of droughts affect the hydrology or the vegetation of the resources evaluated in this study.

- It would be advantageous to partner with other agencies to: 1) inform adjacent developments about landscape-level impacts to resources such as dark night skies and soundscape, and 2) manage the natural processes of pinyon-juniper woodlands across jurisdictional boundaries (national forest lands with pinyon-juniper are located to the west of the park).

- Although not specifically discussed in our series of web articles, the NRCA project also identified action items that would benefit songbirds and the Mexican spotted owl. For songbirds, for example, alternative monitoring approaches or ways to examine currently collected data were suggested to provide data more targeted to birds within the park.

- Three major action areas emerged for the water-based resources: implement a springs and groundwater study to understand surface-groundwater interactions and determine where streams are gaining/losing groundwater across geologic formations; integrate riparian area and springs monitoring by partnering with other federal agencies to manage resources at the watershed level; and monitor streamflow, connectivity, and fish recruitment in streams.

Information in this article was summarized from: Struthers K and Others. 2022. Natural resource conditions at Capitol Reef National Park: Findings & management considerations for selected resources. Natural Resource Report. NPS/NCPN/NRR—2022/2406. National Park Service. Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/nrr-2293700

Last updated: July 14, 2022