Part of a series of articles titled Questions of Land, Labor, and Loyalty: Japanese Incarceration and the Munemitsu Family.

Article

Movement and Migration of the Munemitsu Family

Discover some of the events and forces that shaped the Munemitsu family's story in the lead up to World War II.

Situation of Japanese Americans Pre-World War II

Most of the early Japanese migration to the United States can be traced to Japan’s Meiji Restoration in 1867, which marked a shift in Japan’s political state. Here, the samurai system was overthrown in favor of modernization. This change resulted in the displacement of Japanese people from their lands, leaving many to seek economic opportunity elsewhere.

Fueled by racial discrimination against Chinese workers, the United States enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which outlawed further migration of Chinese Americans to the US and declared their ineligibility for US citizenship. This act cut off a major source of labor within the rapidly industrializing US economy, creating the conditions for Japanese migrants to fill the labor gap.

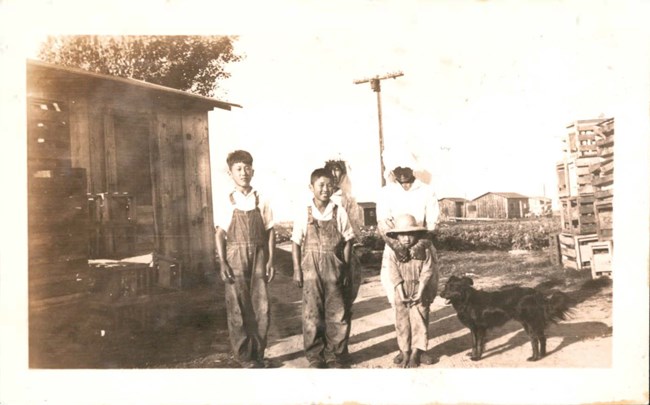

Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University, Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives.

Japanese immigrants first arrived in the Hawaiian islands in the 1860s to work in the sugar plantations. Many further migrated to the West Coast to work in the farming and fishing industries. These early Japanese immigrants are known as the Issei, the first generation of immigrants from Japan, most of whom came to the US between 1885 and 1924.

Once in the United States, Japanese immigrants experienced anti-Asian prejudices and discrimination. The anti-Japanese sentiments manifested into legal restrictions rooted in xenophobia and racial discrimination that prevented Japanese immigrants from becoming US naturalized citizens or property owners. The California Alien Land Law of 1913 prevented first-generation Japanese immigrants from owning land in their name. However, many purchased property in the names of their American-born children. Moreover, the Immigration Act of 1924 prohibited all further Japanese immigration.

Within the Munemitsu family, there are two generations of Issei; parents Fusakichi and Fugio Munemitsu and their son Seima and his wife, Masako Munemitsu. Fusakichi’s second wife, Namaye (Namio) is also part of this generation.[1]

Nisei were second generation Japanese Americans, US citizens by birth, born to Japanese immigrants (Issei) parents. The Munemitsu children, Seiko “Tad”, Saylo, Akiko, and Kazuko Munemitsu are Nisei. Through the discussion of the generational differences, one can gain a fuller understanding of the conditions and situation of Japanese Americans before World War II.

Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University, Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives.

Moving to Westminster: Munemitsu Children and Japanese Americans in American Public Schools

The Munemitsu family moved to Orange County, CA in the early 1930s and bought a 40-acre farm in Westminster under Tad’s name with the help of a family friend. During this time, the Alien Land Laws, anti-immigrant legislation, prohibited “ineligible aliens” from purchasing or owning land. “Ineligible aliens” included immigrants from China, Korea, and India but were generally enforced against Japanese immigrants. With property in their possession, the Munemitsu family was able to gain a better financial foothold in America, thanks to Tad’s status as a US citizen. Soon the Munemitsu family started growing crops like asparagus and other seasonal vegetables.

The Nisei children, Tad, Saylo, Aki and Kazi, were considered a bridge between the Issei and the Nisei in the United States. As a young child, Tad went to the bank with his father, Seima, to translate from Japanese to English and vice versa. The children also attended the local public school; Westminster Seventeenth School was the closest school to the farm.

Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University, Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Orange County school districts did not restrict Japanese Americans from attending “regular” or white public schools, unlike the Mexican American Mendez family a few years later. Tad and Saylo attended Huntington Beach Unified High School, which during the 1930s and 1940s, consisted mostly of white students and a few Japanese students. The younger Munemitsu children, Aki and Kazi, attended the Seventeenth Street School, the very school that turned away Sylvia Mendez and her siblings. Here, Japanese American students, like Tad, experienced racial discrimination through bullying and racial slurs. However, there was no systemic exclusion or school segregation by the school districts between white students and Japanese American students before the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

This article was researched and written by Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[1] Fusakichi Munemitsu immigrated to the US around 1904-08, the exact year is not determined. Fugio Munemitsu died in 1921 at the age of 42, and Fusakichi remarries to Namaye, and they have one son, Samuru (Sam) who is Seima's stepbrother.

“Finding aid for the Munemitsu-Sasaki family collection.” Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives, Leatherby Libraries, Chapman University. Processed by Rand Boyd, July 2010; reprocessed by Annie Tang, July 2019; expanded historical notes researched and written by intern Kathy Morgan, June 2019. Last updated August 2023. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/3/resources/113.

Hittenberger, Jeff. “Aki’s Story: On Relocation and Resilience.” The Deeper Learning Podcast, May 8, 2017. Podcast, website, 35:03. https://deeperlearning.ocde.us/ep-02-akis-story-on-relocation-and-resilience/.

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

“Tad Munemitsu oral history interview conducted by Katharine H. Snope in Garden Grove, California, 1976-08-16.” From the California State University Fullerton, Japanese American Oral History Project. Transcript. https://cdm16855.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/57808 (Accessed March 18, 2023.)

Tang, Annie. “The Munemitsu Legacy: The Japanese American Family Behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s First Successful Desegregation Case.” The Pacific Citizen. December 18, 2020. https://www.pacificcitizen.org/the-munemitsu-legacy/.

Tags

- entangled inequalities

- aapi

- asian american and pacific islander heritage

- asian american and pacific islander history

- migration and immigration

- legal history

- immigration

- immigration and migration

- japanese american

- japanese american history

- japanese american heritage

- westminster

- orange county

- los angeles

- california

Last updated: September 13, 2023