Last updated: October 17, 2024

Article

Massacre at Ross's Landing

Beth Kruse, 2023-2025 Mellon Fellow

"Ye have taken away our dead and where have ye laid them?"

U.S. Superintendent of Cemeteries, Edmund B. Whitman expressed these sentiments, in 1869, when he addressed a large group of U.S. Army Civil War veterans attending their annual reunion. Whitman's rhetorical plea related to the U.S. Quartermaster Department systematic removal of over 137,000 nameless U.S. Civil War soldiers who were reburied in the various National Cemeteries. His address stressed the belief that the intentional Quartermaster's record keeping kept open the door for the "possibility of identifying many of the unknown dead in the future." Whitman argued that the U.S. soldiers were martyrs for the nation who should not be forgotten, and he knew detailed burial records would aid the identification of those moved from battlefields and hospital graveyards postwar and reinterred as "Unknown."

Whitman was correct, nineteenth century newspaper articles led to the discovery of an all but unknown 1864 massacre of Vicksburg United States Colored Troops (USCT) and the Quartermaster's burial ledger combined with U.S. military soldiers' records allowed Vicksburg National Military Park to "restore the name, rank, and regiment and even the date of death, to the occupants of all those graves, which the lapse of time, and by various causalities and accidents had lost their external marks," for the victims killed at Ross's Landing.1

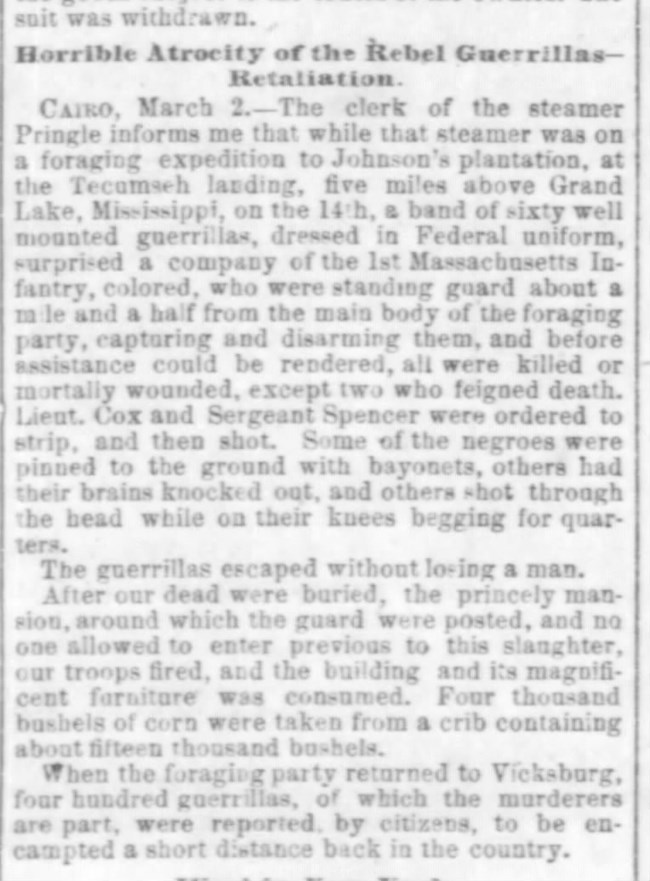

The Feb. 14, 1864 Massacre Reported

In March 1864, the New Orleans Times-Democrat newspaper published a detailed account of a U.S. Civil War massacre involving the 1st Mississippi Infantry (African Descent) and a band of Missouri guerrillas. Two weeks later William Lloyd Garrison’s Boston Liberator, a noted African American newspaper, published a snippet of this event guaranteeing those on the Eastern seaboard knew of the Western massacre. Both reports contained typical nineteenth century sensationalist journalism and factual errors, but the inclusion of this incident in the newspapers ensured that although the event would be forgotten in the post war years, it could not be erased from the history of the Civil War. The correspondents provided just enough tidbits to recover the details of the massacre from the official Union military records, noting these soldiers were wounded or killed in action at Ross’s Landing, Chicot County, Arkansas. Additionally, a Confederate soldier, who participated in the massacre, published a postwar account of the event. His account verifies the reports of a massacre and the “butchery” of the African American soldiers.

Prologue

In February 1864, the U.S. 1st MS Infantry (A.D.) traveled upriver from Vicksburg to Chicot County, Arkansas on foraging detail. Although the newspaper claimed the steamship Pringle transported them, it was more likely the Petrel.2 U.S. Major General William Sherman’s frustration about the Confederate attacks on Mississippi River boats led him to request, in January, five “light-draft gunboats,” for use on the riverways north of Vicksburg. The U.S. Navy sent him the Exchange, Linden, Marmora, Petrel, and Romeo. Sherman needed these ships to provide transport for the U.S. Army regiments to “reconnoiter and threaten” the enemy and “better guard the Mississippi.” Local Confederates continued to attack U.S. soldiers and navy ships even after their surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. These Confederate maneuvers influenced Sherman’s “Hard War” policies concerning confiscating local crops, livestock, homes, and any other material supplies his army needed during the military occupation of Vicksburg. His thoughts about managing civilian assets are found in his Jan. 18, 1864, dispatch to U.S. Navy Lt. Commander E.K. Owen. Sherman informed Owen, “If the enemy burns cotton, we don’t care. It is their property, not ours.” This sentiment was in response to southern planters’ cries regarding Confederate destruction of their property in Union occupied territory.3

The condemnation of “Yankees” and Sherman specifically, for the devastation and seizure of southern crops, horses, and plantations during the Civil War endures. Few recognize that Confederate policies also included burning any resources that the Union army could use if the goods could not be secured by the Confederacy. The Confederate army purposefully destroyed southern citizens’ property without regard to the hardship they inflicted upon the population who largely supported their war effort. For example, in May 1862, the Provost Marshal in Natchez issued a public broadside informing Adams County residents their cotton was subject to burning. The Confederate and U.S. authorities created policy from military necessities and it affected civilians. Sherman reasoned, “so long as they have cotton, corn, horses, or anything, we will appropriate it or destroy it so long as their confederates in war act in violence to us and our lawful commerce.”4 It was under this mandate that found U.S. soldiers belonging to Co. G, 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) foraging on “Tecumseh” Plantation just north of Grand Lake, Arkansas.

The armies in the field needed the local crops and livestock to feed themselves and their horses. This meant the citizens found themselves regularly visited by U.S. and Confederate soldiers as well as Confederate guerrillas, so much so that in the fall of 1864 John MacLean of Bayou Mound wrote to Confederate General D.H. Reynolds complaining, “we have been tossed and tumbled about considerably by both Federals and our own soldiers and then by bands of independent marauders.”5 Reynolds, like other Confederate Generals in Union occupied territory, could not halt the formidable U.S. army nor could they completely control the outrages committed by their own guerrilla forces. One of the most brutal outrages of Chicot County happened on Feb. 14, 1864, when a small number of Confederate guerillas attacked the U.S.1st MS Inf. (A.D.) foraging party. The Times Democrat article claimed that 4,000 bushels of corn was confiscated on that Valentine’s Day, but the U.S. soldiers returned to Vicksburg only after they buried thirteen of their murdered comrades.

Boston Public Library

Massacre

The 1864 newspapers provided the overall picture of the massacre, correctly noting the attack was by guerrillas associated with Missouri, but incorrectly attributed the massacre to the infamous Quantrill Raiders. A post war account by one of the Confederate guerrillas involved in the massacre revealed who the attackers were and attests to the brutality of the surprise attack. In 1911, Private “Weed” Marshall of Co. E, 9th MO Cavalry submitted his account of the massacre to the Confederate Veteran, so it could be added to the list of small skirmishes that were “the most destructive and fatal of the war.” Marshall claimed a local citizen informed Captain W.N. “Tuck” Thorp’s scouts that Union forces were nearby. Marshall omits the fact that the “Federals” were African American U.S. Army soldiers. Undoubtedly, the citizen shared this information, and that fact was the primary reason for the massacre. Thorp put to vote whether his company would “go” or “no” and attack the forage party. They readily voted to attack. Marshall acknowledges their willingness related to the men’s status as “half-bushwhackers.”6 Bushwhackers was a derogatory term usually used by Union sympathizers to describe Confederate guerrillas who were the “lowest and meanest type.”7 It seems Marshall cherished the idea that he was an unofficial guerrilla fighter above being recognized as a Confederate "common" soldier. The lack of any Confederate official records for the 9th MO Cavalry, that the attack was put to a vote and not a military order, plus the fact that they gave “no quarter” indicates they were, in fact, entirely an irregular Confederate guerrilla unit.

Twenty-one men of Thorp's group elected to go and when the guerrilla band arrived at "Tecumseh" plantation, they found the U.S. 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) near the cotton gin house.8 One of the African American soldiers fired off a shot that alerted the rest of the company of imminent danger. When the mounted guerillas rounded the building, the U.S. soldiers stood ready in line and fired simultaneously. The U.S. 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) fighting equipment consisted of Austrian Lorenz Rifles, which were one shot muzzleloaders with unique quadrangle shaped bayonets. The mounted guerrilla cavalry advanced upon the African American infantry soldiers so swiftly that the African American soldiers did not have time to reload and were forced to quickly retreat. They did not get far as Thorp’s guerilla band continued firing shots from their Colt navy and dragoon revolvers. According to Marshall, “two minutes of clearing the gate not a Yankee was alive.” Thorp and his men were not satisfied with only shooting the African American soldiers in the back and leaving them lay on the ground. Marshall confirmed what the newspaper accounts suggested that the Missouri guerrillas dismounted and seized the U.S. 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) rifles and “pinned each one to the ground” with their own Union bayonets.9

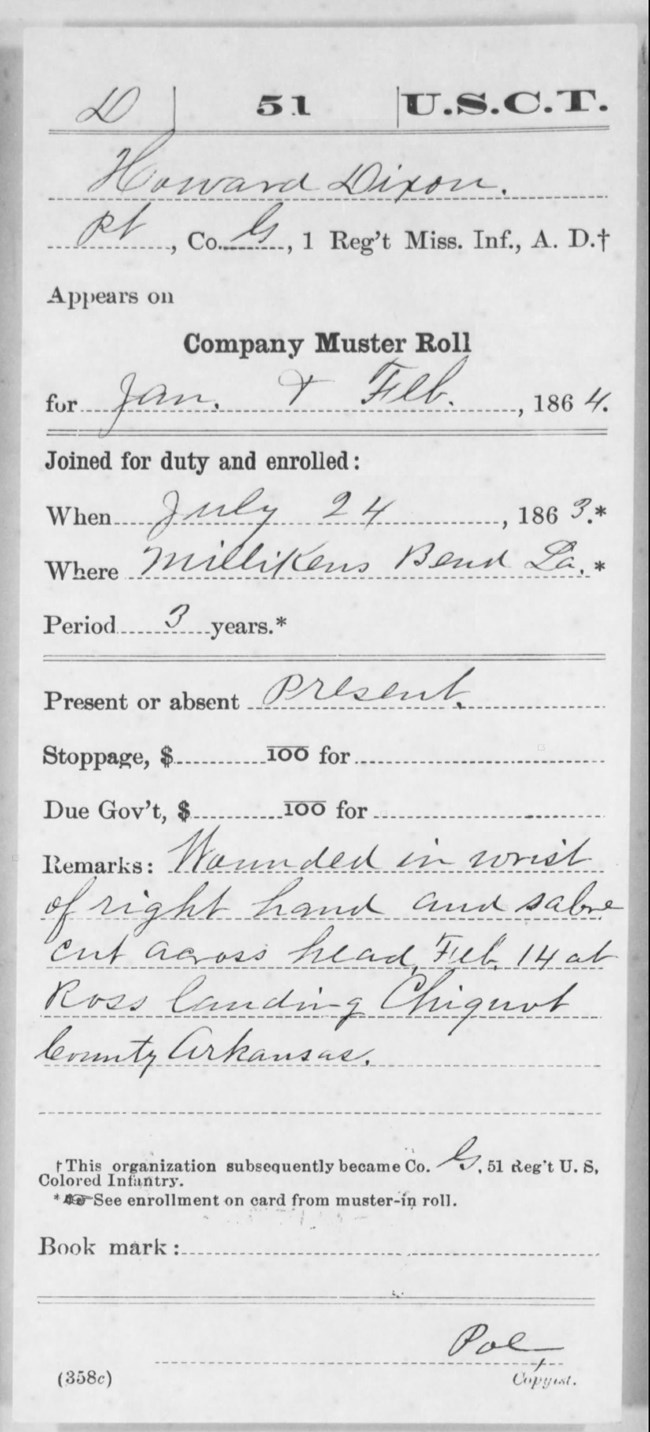

Fold3

The tone of Marshall’s account is one of pride in killing defenseless “Yankees.” He even ended his story praising the Missouri soldiers, claiming “every soldier did his part well.” Marshall also included the twenty-one names and places of residency of the former guerrilla band to ensure that they received full credit for their actions. Marshall's post war pride in massacring African American U.S. soldiers is not unique and can be found in other Confederate published and unpublished memoirs. Postwar delight in massacring defenseless enemy soldiers certainly challenges the “Lost Cause” mythological belief that Confederate soldiers were “heroic and saintly” and worthy of monuments in their honor.12

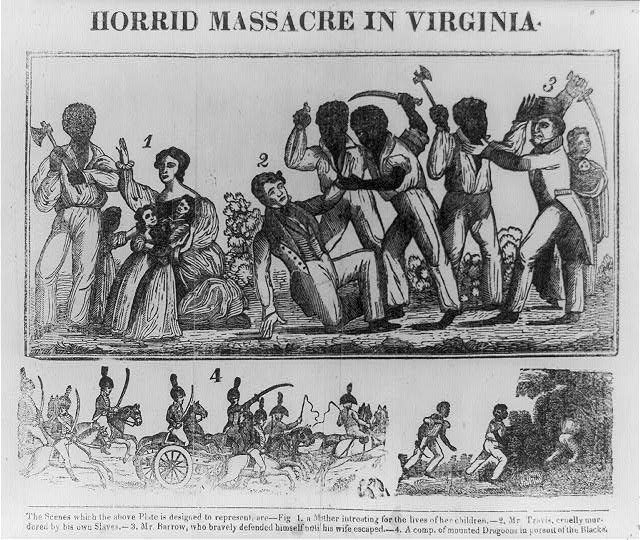

Sadly, the Valentine’s Day Massacre of the 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) at Ross Landing, was not a singular event in U.S. Civil War history. A long-standing white fear of servile insurrection dating back to colonial times influenced the decision of Confederate soldiers to massacre USCT on battlefields and suggests a less than a genteel nature of southern soldiers. There was no act more horrifying to the majority of southerners than the agency shown by enslaved people when they revolted against their oppressors and killed them. The successful 1804 Haiti revolt and the failed 1831 Nat Turner Rebellion heightened white anxiety and resulted in more extreme slave codes. The white enslavers fear of armed rebellion became a reality with the formation of Union African American fighting regiments, in 1863. The mere thought of southern white soldiers facing armed African American Union soldiers influenced the creation of U.S. Civil War military policies and triggered massacres on the battlefields.

Library of Congress

Policies Regarding USCT on the Battlefields

The Confederate outrage against the threat of an “armed slave insurrection” was readily apparent as soon as Abraham Lincoln released the conditions of his Emancipation Proclamation. On Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln's Presidential Executive Order authorized the inclusion of African American males to not just perform labor duties for the U.S. Army but take up arms as soldiers. Lincoln’s response to northern Free Black leaders and enslaved runaways who advocated for their rights to join the Union army as soldiers culminated in the inclusion of this provision in the proclamation. Southerners who supported the Confederate war efforts howled at the idea their soldiers would face armed African Americans on battlefields. Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s 1862 Christmas Eve Proclamation declared that all captured enslaved men were to be turned over to State authorities “to be dealt with according to the laws of said States” and all commissioned white officers leading the USCT units were not to be considered soldiers and “whenever captured, reserved for execution.”13 In short, a graduate of West Point Military Academy and former U.S. military officer ordered the execution of soldiers on the field, ignoring all accepted standards regarding conduct of war and treatment of prisoners. Davis's condemnation fueled the flames and set the stage for Confederate soldiers' behavior on the battlefield.

To be clear the state laws for servile insurrection were execution, but the need for enslaved labor especially in wartime resulted in captured African American U.S. soldiers’ impressment on military fortifications, not their state executions. Lincoln responded to the Confederacy’s policies to execute captured Union soldiers by issuing General Order #252. In it he ordered for each U.S. soldier executed, a Confederate soldier would also be executed. The fear of Union retaliation and need for labor led to the Confederate government to override Jefferson Davis's directive and change their policy to imprisonment for white officers and impressment for the African American soldiers. However, official rules did not prevent Confederate soldiers and guerrillas, in the field, from massacring USCT officers and soldiers.

On Valentine’s Day 1864, Thorp’s guerrillas maliciously executed the white officers of the Union foraging party. Lieutenant Colonel Thaddeus Cock’s U.S. military record includes a death index card stating he was “Shot through the mouth after surrendering. Left for dead on the field.”14 The contemporary newsprint provided snippets of the February 14, 1864, event and judged it as an atrocity, but no reports of it are found in the Official Records of the War of Rebellion. The small number of USCT involved meant it was largely overlooked and quickly forgotten. It was also overshadowed by larger 1864 USCT massacres that soon followed: Ocean Pond on Feb. 20; Ft. Pillow on April 12, Poison Spring on April 18.

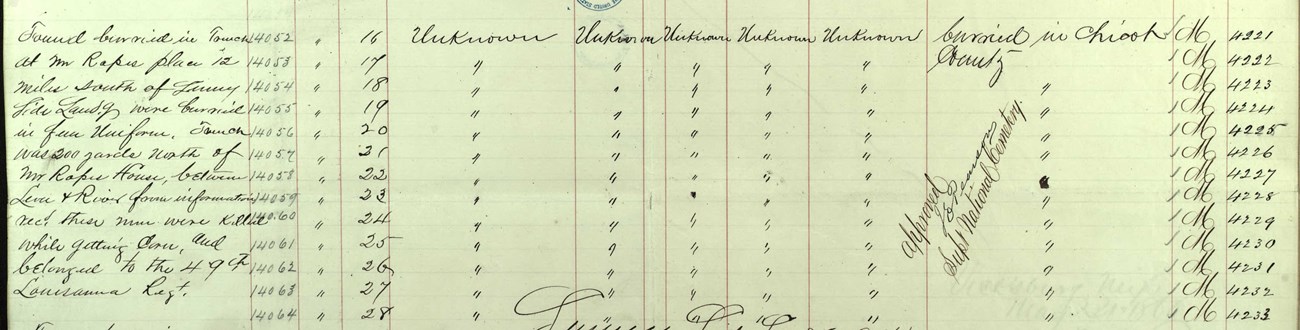

NARA

Epilogue

In April 1866, Congress authorized the Secretary of War “to take immediate measures to preserve from desecration the graves of soldiers of the United States who fell in battle or died of disease in the field and in hospital during the war of the rebellion,” and “secure suitable burial places,” which led the creation of Vicksburg National Cemetery.15 By 1868, the total number of reinterments equaled 15,580. That number included 5,553 USCT of whom 98% were recorded as “unknowns.”16 The loss of nearly all the identities of the USCT in contrast to the identification of 60% of the white soldiers is due to lack of military identification of all soldiers during the Civil War but is also an indication of nineteenth century inequality.

An example of both race and class inequality is found in the burial of the two white officers who were killed. The U.S. Army returned the bodies of white officers Thaddeus Cock and James Spencer to their families. These two officers were buried following typical funerary customs and included notable headstones and inscriptions. Thaddeus Cock’s epitaph reads, "He died for his country, a martyr to the cause of freedom, a victim to the barbarism of Slavery. 1st Lt. of Co. G, 1st Miss colored infantry, cruelly murdered after having surrendered as a prisoner of war." 1st Sgt. James Spencer’s Indiana tombstone notes his Masonic affiliation and that he was “killed at Tecumseh Landing, Miss.”17 The officer's families knew where their soldiers were buried and could visit and care for their gravesites. In contrast, there are no headstones for the other eighteen men who were massacred or wounded at Ross’s Landing. Only ground-level numbered square shafts mark their final resting spot. Their names and circumstances of their battlefield executions were known as seen in the Vicksburg reinterment ledger and Union military files, but their bodies were left unidentified, only to be rediscovered and honored in 2024.

Beth Kruse, 2023-2025 Mellon Fellow.

All sixteen enlisted men of the U.S. 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) victims, who died from the massacre at Ross’s Landing, lay in unmarked grave shafts within the Vicksburg National Cemetery. In March 1868, the thirteen originally buried in Chicot County were moved to the Vicksburg National Cemetery and laid in the segregated section M #14900 to 14912. The two USCT who lived until 1918, Privates Ruffian Epps and Howard Dixon's gravesites are still unknown.

Beth Kruse, 2023-2025 Mellon Fellow

Restoring Identities to the "Unknown"

Thirteen massacred Co. G, 1st MS Inf. (A.D.) buried at Vicksburg National Cemetery as “Unknowns” in Section M #14900-14911.

|

Pvt. Calvin Cathron |

Pvt. John Genefa |

Pvt. Isaac Stanton |

|

Corp. Fleming Epps |

Pvt. Anthony Givens |

Pvt. Isom Taylor |

|

Corp. Peter Everman |

Pvt. Richard James |

Corp. Nelson Walker |

|

Pvt. Charles Farrar |

Sgt. Tony McKee |

|

|

Pvt. Henry Ford |

Pvt. Thomas Ransom |

|

Pvt. Henry Berry

- Wounded and died, on March 23, 1864, at the Regimental Hospital in Goodrich Landing, LA exact location of reinterment at Vicksburg National Cemetery unknown.

Noah Powell

- Wounded and died, on Feb. 18, 1864, at the Regimental Hospital in Vicksburg exact location of reinterment at Vicksburg National Cemetery unknown.

Pvt. James H. Boldin

- Wounded and died, on Jan. 4, 1866, almost two years later at Alexandria, LA of “Epilepsy” in “Company quarters.” Exact location of reinterment at Vicksburg National Cemetery unknown.

Pvt. Howard Dixon

- Wounded and survived the war: died May 1, 1918, at Delhi, LA.

Pvt. Ruffian Epps

- Wounded and survived the war: died April 24, 1918, at Gunnison, MS.

1st Lt. Thaddeus Cock

-

Executed white officer: “Shot through mouth after surrendering. Left for dead on the field.” Died in Vicksburg Regimental Hospital Feb. 28, 1864, Buried in Canton, OH.

1st Sgt. James Spencer

- Executed white officer. KIA Ross’s Landing. Buried in Decatur, IN.

Footnotes

- Grand Army of the Republic Publishing Committee, The Army Reunion with Reports of the Meeting [1868] of the Societies of the Army of the Cumberland, Army of the Tennessee, Army of the Ohio, and Army of Georgia, (Chicago: S.C. Griggs and Co., 1869), 225-235. Total “Unknown” tabulation from John R. Neff’s Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation, (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 2004), Appendix A. Note there is one significant typographical error in total USCT unknown; print erroneously transposed the accurate number of 19,531 to 91,531.

- Not to be confused with the Confederate privateer frigate Petrel sunk on the Eastern Seaboard in 1861. The Confederates in Mississippi captured the U.S. Petrel steamboat and destroyed it on the Yazoo River, April 22, 1864.

- Office of the Secretary of the Navy, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I Vol. XXV, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 703; 705; 724-725; 754. A clerk from the Pringle is recognized as telling the story to a war correspondent in Cairo, IL and some news articles identify the steamer as taking part. There is a possibility the commercial steamer Pringle was the transport, but the lack of any mention of the Pringle in the Official Records of the Army or Navies on the southern portion of the Mississippi River, in 1864, suggests it is unlikely the Pringle was involved. Significantly, the Pringle was not included in U.S. Rear-Admiral David D. Porter's Feb. 1864 report of vessels in the Mississippi Squadron. On the other hand, on Jan. 20, 1864, Lt.-Commander E.K. Owen reported to Rear-Admiral Porter noting the Petrel was docked at Greenville, MS which is across the river from Chicot County, AR.

- Ibid., 725.

- John MacLean to Gen. D.H. Reynolds, Oct. 16, 1864, Daniel Harris Reynolds Papers, MS R32, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, quoted by Leo Huff in "Guerillas, Jayhawkers, and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas," Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer,1965), 143.

- Weed Marshall,"Fight to Finish Near Lake Village, ARK," Confederate Veteran, Vol. 19, (1911), 169. The Confederate Veteran was a monthly subscription periodical aimed at promoting a one-sided southern version of the Civil War battles soldiers and postwar commemoration events and monuments.

- Leo Huff in "Guerillas, Jayhawkers, and Bushwhackers in Northern Arkansas," Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer,1965), 128-130.

- “Tecumseh” Plantation was originally owned by Richard M. Johnson. The name relates to Johnson being credited with killing famed Native American leader Tecumseh in the War of 1812. Johnson was Vice-President of the U.S. under Martin Van Buren. Information from pamphlet, "Johnson Family Levee Tour: Between Lake Chicot and Grand Lake," Lakeport Plantation, An Arkansas State University Heritage Site.

- Weed Marshall, “Fight to the Finish,” 169.

- Frederic Dyer, A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion: Compiled and Arranged from Official Records of the Federal and Confederate Armies, Reports of the Adjutant Generals of the Several States, The Army Registers, and Other Reliable Documents and Sources, (Des Moines: Dyer Publishing Co., 1908), 11.

- "Howard Dixon," Co G, 51st USCT, CMSR, Roll 89, Fold3. Howard Dixon remained in the Vicksburg area for some time after the war. He is found as “Howard Dickson” Co. G, 51st USCT in the 1890 Veteran’s Census.

- Caroline Janney, “The Lost Cause,” Encyclopedia Virginia, Virginia Humanities, (Dec. 7, 2020).

- Office of Secretary of War, The War of the Rebellion Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, (Washington, D.C.: GPO,1899), 795-797.

- "Thaddeus Cock," Co G, 51st USCT, CMSR, Roll 89, Fold3.

- Richard Meyers, The Vicksburg National Cemetery: Administrative History, (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, 1968), Appendix A.

- Quartermaster General’s Office, Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defense of the American Union, Interred in the National Cemeteries, Vol. XXIV and XXVII, (Washington, D.C., 1869;1871).

- Thaddeus Cock and James Spencer’s grave markers are found on Find-a-Grave website.