Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

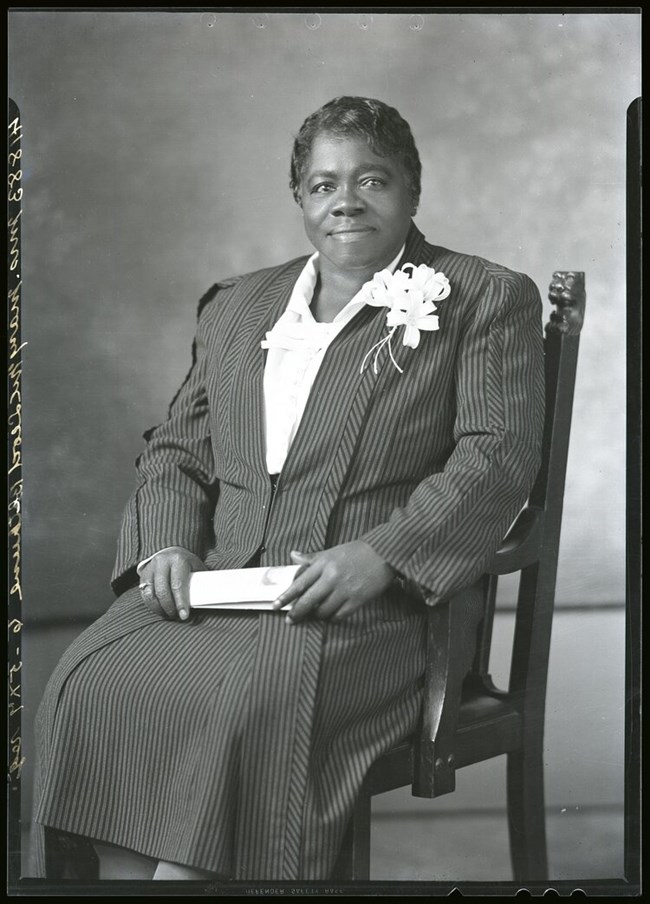

Mary McLeod Bethune, True Democracy, and the Fight for Universal Suffrage

When she undertook to redefine her career goal, she encountered Lucy Craft Laney (1854-1933). Like Bethune, Laney was a daughter of the South, a Presbyterian, and the child of formerly enslaved parents. Laney encouraged Bethune to make educating the youth her mission field. The damage caused by enslavement and widespread poverty in the post-emancipation South created the need for community institutions and structure. Laney believed that education paved the way to citizenship, stronger families, and better communities, thus elevating all Americans. Laney’s Haines Normal and Industrial Institute in Augusta, Georgia, provided a model for Bethune.

Bethune selected northern Florida for her school’s location because there were increasing numbers of African Americans migrating there, and others already prospering in the Daytona Beach area. Despite this growing African-American population or perhaps because of it, Bethune, arriving in 1900, encountered a racially hostile state. Florida had the highest lynching rate in the country, where over 260 black Floridians were lynched between 1882 and 1930. Nevertheless, black Floridians persisted in attempting to vote and to defend themselves and their communities from white terrorism when exercising the franchise. The black community linked political power with economic justice principally for the working class. As early as the 1880s, black women engaged in the political process through encouraging their men to register, vote, and form interracial alliances to better the opportunities for the laboring class. White conservatives ferociously beat back every effort; one important strategy used was to establish a one-party rule of state government. Florida’s 1885 Constitutional Convention also instituted a poll tax. However, in the first season of women’s suffrage, women were exempt from paying the poll tax but racial tensions remained high. It was in this atmosphere that Bethune followed Laney’s early advice to make educating the youth her mission field, and she worked tirelessly as an educator to prepare her students for life and the responsibility of the vote.

Following her initial affiliation with the NACW and still living and running her school in Florida, Bethune also joined other African-American women such as Eartha M.M. White in the Florida State Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. White, an activist in the established tradition of Floridian women, worked through the black women’s clubs to organize and educate African-American voters. Bethune joined the campaign and added a second prong to her mission field – universal suffrage -- stating:

In 1912 Bethune attended the NACW meeting in Hampton, Virginia. At this meeting she delivered an address which was part biography and part a fundraising endeavor for her school. Throughout the meeting, the agenda addressed all aspects of discrimination African Americans encountered regularly, ranging from police harassment to lack of reliable employment opportunities. However, at the forefront of everyone’s mind was one of the hottest issues of the day – women’s suffrage. In 1912 only nine states allowed women to vote; and it wasn’t until 1919 that the 19th Amendment, nicknamed the “Anthony Amendment” would extend the franchise to women through passage of a federal amendment to the Constitution to be ratified by the states.“Eat your bread without butter but pay your poll tax! Nobody ever told me to pay my poll tax. My dollar is always there on time. Do not be afraid of the Klan. Quit running. Hold your head up high. Look every man straight in the eye and make no apology to anyone because of race or color. When you see a burning cross remember the Son of God who bore the heaviest.” [1]

Dr. Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, a leader in suffrage scholarship and the author of African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920 (1998), argues that there were three generations of African-American suffragists. Bethune is in the third generation: 1900-1920. The third generation sought to build interracial coalitions in all regions of the country. However, the proliferation of African-American suffrage activity followed a different arc than that followed by white women. The ever-present threat in Florida to the African-American community fused all matters of access and equality into the larger pursuit of full citizenship, with the aims and intentions of lifting their community out of imposed ignorance and lack of equitable state funding into civic literacy and better wages:

Thus, Bethune’s activism through her school’s sprawling social engagement also provided interracial space for secret meetings and suffrage work. In 1920, she and Laney created the Southeastern Federation of Women’s Clubs which galvanized African-American women in all southeastern states. This important work continued to prove necessary even after the ratification of the 19th Amendment as the political climate throughout Florida and most of the southeastern region precluded scores of African Americans from voting. For African Americans in central and southern Florida, their hopes were virtually extinguished for the next four decades. In the face of this, Bethune continued her civic work in the NACW, becoming national president in 1924. Bethune’s vision for the NACW was one of true unity, bridging all prejudice from regional origin, and economic class differences.“By the first decade of the twentieth century, the politicization intensified as a critical mass of African American women’s organizations developed to push for the enfranchisement of all Black women as a means to protect Black communities, and for the re-enfranchisement of Black men whose votes had been stolen from them.” [2]

Courtesy of Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

More than 30 years later, on September 6, 1952, Bethune penned an article “Women Should Vote in Tribute to Those Who Fought for the Ballot.” She was still arguing for unity, the end of prejudice, and economic equity among all citizens, all supported by universal franchise. In this article she extolled the tenacity of pioneering women who fought long and hard to “bring full citizenship to all the people.” African Americans still had decades of struggle ahead with the Civil Rights Movement and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and beyond to come close to the promise of the 19th Amendment, and Bethune recalled their suffragist history to inspire them. Once again following her lead, African-American women did persist and continue to make strides in political agency through voter education, protests, and direct-action campaigns. Bethune insisted it was incumbent upon modern women to ensure that the franchise “promot[ed] security at home, and mutual respect and peace among the peoples of the world.” [4]

Mary McLeod Bethune did not wield a picket sign or participate in the 1913 suffrage parade. She was crafting and modeling behavior for future women voters. On November 19, 1949, Mrs. Bethune was asked, “If you could live your life over what would you do?” Bethune responded, “Head straight to New York and run for Congress [or maybe a stint] in the diplomatic service.”[5] Profoundly aware of the impact voting and political office had within the country, she believed that principled voices -- be they female or male -- could bring about the victory of democracy over dictatorship. “The free ballot…universal adult suffrage [would allow African Americans the ability] to vote out all the advocates of racism and vote in those whose records show that they actually practice democracy.”[6] Her brand of gendered universal suffrage challenged “Negro women” on all levels and classes to march forward toward peace, justice, and democracy for all at the ballot box.

Dr. Ida E. Jones is the inaugural University Archivist for Morgan State University. She is the author of The Heart of the Race Problem The Life of Kelly Miller (2011); Mary McLeod Bethune, Activism and Education in Washington, D.C. (2013); William Henry Jernagin in Washington, D.C.: Faith in the Fight for Civil Rights in Washington, D.C. (2015); and most recently Baltimore City Rights Leader: Victorine Q. Adams, the Power of the Ballot (2019) which won the African-American Historical and Genealogical Society’s International biography book award. She curated an online exhibition for the National Women’s History Museum “Claiming Their Citizenship: African American Women From 1624-2009.” She is the former managing editor of the Negro History Bulletin 1999 to 2005. She is a former National Director of the Association of Black Women Historians 2011-2013. Jones has appeared on CSPAN, National Public Radio, BBC radio and in numerous publications. She is currently co-vice president of Baltimore City Historical Society and managing editor of the Gaslight BCHS’s newsletter. She is a newly appointed Board member of the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites. She is an adjunct faculty member at Lancaster Bible College. Jones believes deeply in the words of Mrs. Bethune who said, “power must walk hand in hand with humility and the intellect must have a soul.”

Footnotes

[1] Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida From Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press (2005), p. 194.

[2] Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; Second Printing edition (May 22, 1998), p. 82.

[3] McCluskey, Audrey Thomas. A Forgotten Sisterhood: Pioneering Black Women Educators and Activists in the Jim Crow South. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield (2014), p. 65.

[4] Bethune, Mary McLeod. “Women Should Vote in Tribute to Those Who Fought for the Ballot,” The Chicago Defender (September 6, 1952), p. 10.

[5] Taylor, Lois. “Would Head for Congress, Says Retiring National Council Head,” Afro American (November 19, 1949), p. 10.

[6] McCluskey, Audrey Thomas. & Elaine M. Smith (eds.). Mary McLeod Bethune Building a Better World. Bloomington, IN Indiana University Press (1999), p. 20.

Bibliography

Bethune, Mary McLeod. “Women Should Vote in Tribute to Those Who Fought for the Ballot,” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) September 6, 1952 pg. 10.

Hanson, Joyce A. Mary McLeod Bethune and Black Women's Political Activism. Columbia, MO, University of Missouri; First edition (March 14, 2003).

McCluskey, Audrey Thomas. A Forgotten Sisterhood Pioneering Black Women Educators and Activists in the Jim Crow South. Lanham, MD. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

McCluskey, Audrey Thomas. & Elaine M. Smith (eds.). Mary McLeod Bethune Building a Better World. Bloomington, IN Indiana University Press, 1999.

Ortiz, Paul. Emancipation Betrayed: The Hidden History of Black Organizing and White Violence in Florida From Reconstruction to the Bloody Election of 1920. Berkeley, CA University of California Press, 2005.

Robertson, Ashley N. Mary McLeod Bethune in Florida Bringing Social Justice to the Sunshine State. Charleston, SC The History Press, 2015.

Taylor, Lois. “Would Head for Congress, Says Retiring National Council Head,” Afro American, November 19, 1949, p. 10.

Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn. African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850-1920. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; Second Printing edition (May 22, 1998).

Wesley, Charles H. The History of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs: A Legacy of Service. Washington, DC.: National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, Inc., 1984.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- mary mcleod bethune council house national historic site

- women's rights national historical park

- women's history

- african american history

- reconstruction

- political history

- suffrage

- 19th amendment

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- religious history

- history of education

- georgia

- florida

Last updated: December 14, 2020