Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Managing Environmental Change in Cultural Landscapes: Built Environment

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

This presentation, transcript, and video are of the Texas Cultural Landscape Symposium, February 23-26, Waco, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of this presentation on YouTube.

National Park Service

Lauren Meyer: Good afternoon, everyone. Thank you. So, it's hard to follow Susan [Dolan] because I feel like you're so soothing and it's actually good for me because it keeps the nerves down so it feels good. So, to follow Susan's presentation on the living elements of the cultural landscape, my presentation is going to focus on the built elements of the cultural landscape and managing change in light of climate change and looking at a couple of projects that we as the Vanishing Treasures Program had been working on over the last several years.

So, the first thing I just want to bring up is a comment on the inter-relatedness of cultural resources, right? So, I think we've heard it in all the presentations that we've listened to today, that everything is interdisciplinary, right? All resources, conditions of resources, damage, loss, change to landscapes, change to features impact other features across the landscape, right? So, why am I here talking about the built environment? Because changes to that built environment change the value, the context, the significance, the integrity or impact and how you evaluate those things within a broader cultural landscape.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

So, like natural resources, they should be viewed as systems. One thing affects the other. Management and treatment decisions regarding one feature impact others. As you're changing things, you're effecting viewsheds, right? If there are impacts to a building, if you lose features to a building, you're impacting that viewshed. Very often a building is built in an environment because of its surrounding elements. It was put there because of the protective nature of the geology or the landscape or because of its proximity to water features to springs, and because of things that you can see from the location of the building. When you're talking about especially pre-contact architecture and again, loss of any one element impacts the overall significance and integrity.

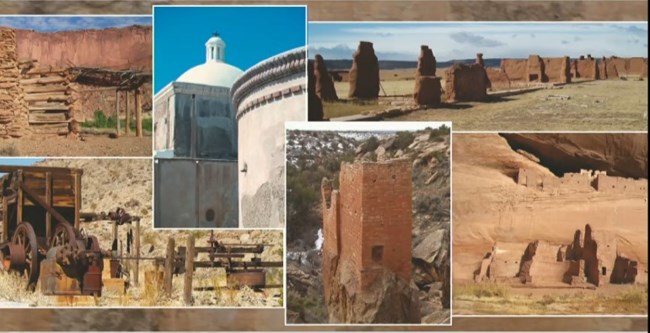

So, the resources that I focus on in my work are not all of the built environment. I'm not talking about those pieces of architecture that inherently protect themselves with roofs and windows and doors. The resources that we work with, with the Vanishing Treasures Program are a lot more fragile. They are generally those resources out in the west that are in a state of ruin, that are preserved in an as-found condition, that need us to help them to survive. This is just a few and what are those resources? I'll just show you a handful.

So, Native American resources, pre-contact and historic period. The mission sites. San Antonio missions and Salinas Pueblo missions in New Mexico, the Indian War era forts at Fort Union and Fort Davis and other sort of Anglo settlements that we see across the landscape. And this is really just to show you pretty pictures of the resources that we work with in the Park Service. And then going into some more modern, this is also sort of industrial heritage, right? The kilns at Death Valley and some of the mining sites, Death Valley and Joshua Tree, Mojave. Some of these resources are world heritage sites. You have one here with San Antonio Missions, Choco Canyon. And some of them are vernacular, small scale, built of the Earth, local materials, really unassuming. So, there's a pretty broad range, and the materials are fragile. We're talking about earthen materials, local materials, things that the environment will immediately have an impact on.

So, you can see by the resources that we work with, why climate change is such a concern of ours. When you look at those resources, you look at what's missing from those resources. Again, they have no roofs. They have no windows, they have no closure systems. They don't have anything to inherently protect them. They're built of ancient and fragile materials. Materials that when impacted by environmental change, you will see an immediate response.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

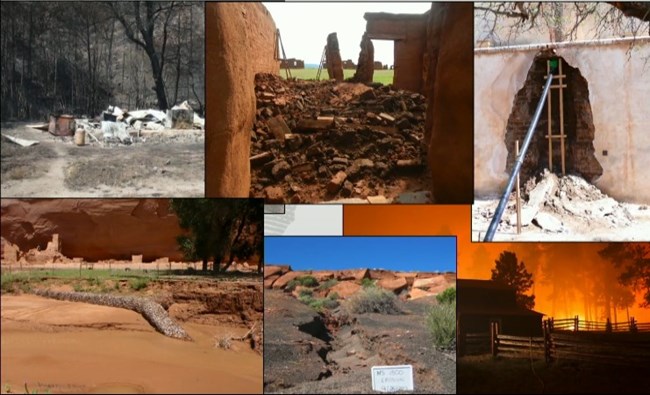

In 2010, we were fielding questions, comments, and concerns coming in from our parks across the region of serious impacts that they were seeing as a result of changing climate. Severe weather events, severe rain events causing degradation and serious loss. Monumental wall collapses in some of our parks. They really are the canaries in the coal mine, right? Starting from the adobe resources and moving up, but still again, unprotected out in the environment, needing human intervention to help them survive. But again, these resources were built into a certain environment to survive in a certain environment and those conditions are now changing.

So, what's happening? With temperature increases, we're seeing increases in fuel loading and severe fire conditions that are threatening and also destroying resources across our landscape. We're seeing severe weather events, mostly big rain events occurring that are causing serious, again, monumental collapse in some of our resources, losing features and losing complete walls and groupings of sites. Erosion, this one's for you. So, severe erosion across the landscape, right? Vegetation communities are changing. What happens when vegetation communities are migrating and changing? Soil conditions are changing. We lose soil stability. What happens then? We have serious erosion, but that instability of soil also causes instability to our architectural components. Again, as we're seeing these severe rain events, we're seeing changes to hydrologic patterns, flooding, which you all have seen here in Texas as well.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

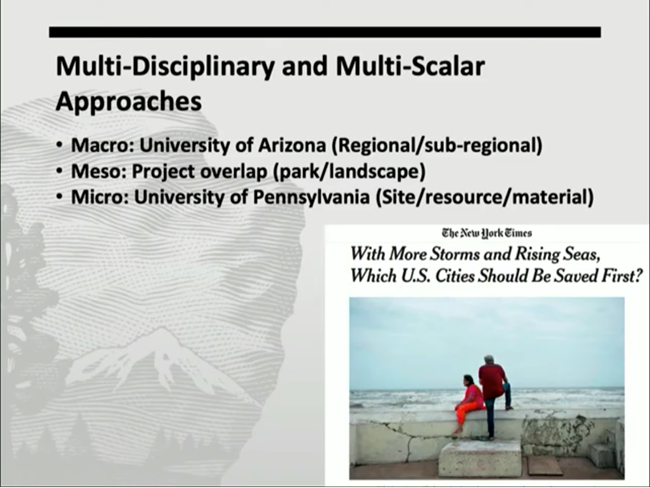

So, what are we doing to address this? So, we've been developing over time projects with our parks and with our partners that are multi-scaler, meaning from the ground up to 30,000 foot level and back down again. And also multidisciplinary. Acknowledging that we have to be working with our partners in natural resources and climate science. We have to be working across cultural resources disciplines in order to develop approaches that are targeted to the changes that are happening and to the resources that we're protecting. And it's all about prioritization. We're going to lose things. None of us like to admit that or acknowledge that, but we are. We don't have the capacity, we don't have the funding, we don't have the people to be able to maintain and manage the resources at the levels that we would like to be doing so.

So, how do we make those decisions? So in our program, we've been working at sort of three levels, that macro sort of 30,000 foot level, the region and the park level with the University of Arizona to develop approaches to sort of identify hotspots that we can then sort of drill down into. And once those hotspots are identified, we look at things again at that park level and at smaller landscape scale. And then the micro level on the ground. How do we take those hotspots, drill down into those hotspots and get a better understanding for what's happening to a particular resource, to the materials within that resource, and start making decisions about how we apply treatments? And some of those treatments are going to be very different from what our traditional approaches might be.

I'm going to quickly go through just these couple of projects. The first, that sort of 30,000 foot view down to the sort of park scale, the development of a vulnerability visualization tool and an assessment framework. You can see the team is interdisciplinary. It's the University of Arizona's Institute of the Environment, the Natural Resources and Environment and Remote Sensing Center, the Architecture Planning and Landscape Architecture Department, and then within the park service, the Vanishing Treasures Program. And then several other parks and programs, natural resources, cultural resources and parks with the ultimate goal of developing a framework to identify and address vulnerabilities of cultural resources to environmental stressors and weathering with a focus on what is formerly the Intermountain Region of the National Park Service.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

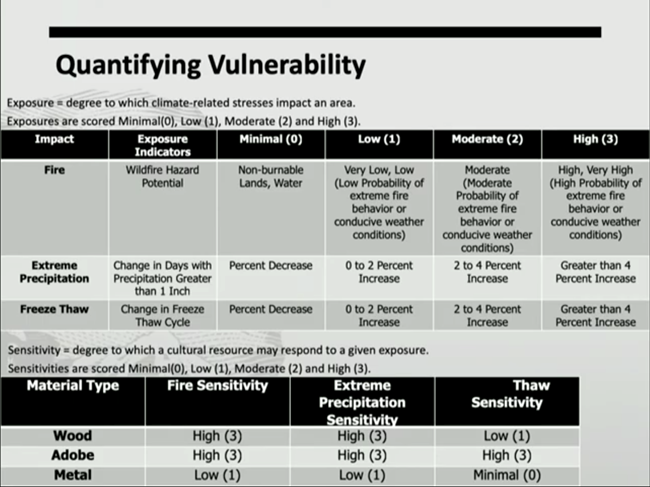

So, there are a few elements to this project and some of this is coming from other projects that are ongoing internationally, locally, and coastal issues. You know we're trying to pull from things that are already out there rather than trying to reinvent the wheel. But we have to acknowledge that some of the resources that we work with in these western parks are unique and it's really hard to apply some of the frameworks that are being developed for coastal resources or arctic resources to those resources that are living in the desert southwest. So, the first piece is to quantify, and again, really hard to quantify, right? We're trying to put numbers to certain things that you really can't quantify with numbers. So, the first piece is exposure. We've got that down. A lot of that is coming from our clients, the climate scientists, and it really is the degree to which climate related stressors impact an area.

So, we're identifying those exposures that we believe will have the most impact to cultural heritage and to the built environment, and we're creating parameters and creating scales. The second piece, which is a lot more complex, is sensitivity. How do you determine how sensitive a resource is to those climate stressors? Well, some of it is qualitative, some of it is quantitative, but in order to help us prioritize, we really need to sort of figure out ways to put numbers even to that qualitative data. So, we're starting with materials, locations, conditions, looking across the range of things that make a resource sensitive and trying to apply numbers to that.

One of those pieces are materials. So, materials respond immediately to their environment, particularly when they don't have those protective features, such as roofs. So, we made an attempt at looking at those materials and identifying, based on those exposures, what their sensitivity might be. But that's not everything.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

There's a lot more that needs to be done. Again, current condition of a resource in tandem with the material vulnerabilities, material sensitivities, in tandem with their location, and slope, and all of these other factors really do come into play when you're talking about sensitivity. So, we continue to work on that. And once we get to sensitivity, there's a whole other issue with significance. And that significance overlay really does result in prioritization and it's not just National Register significance. We also need to be working with our partners in traditional communities and within the tribal communities to figure out how you apply significance. Not only based, again, on sort of Western views, but across the board because so many of our resources are of those cultures that live in proximity to those resources.

One piece of this project is to develop a visualization tool because for us, it really does feel like it's easier to understand it when you see it, right? So, we're working with the geospatial programs at the University of Arizona to develop this risk visualization tool. Again, computer model, based on existing data layers. You can zoom into a park or a location, you can overlay existing data sets. So, the cultural resources, GIS data layers, and in the Park Service, we have systems: List of Classified Structures, Cultural Landscapes, Inventory, and Archeological Site Management Inventory. To be able to pull data from those datasets on location, on condition, and overlay them onto the system, and then go into the exposure layers, add those exposure layers and see what it's telling us.

Red to blue, hot to cold, which things are sitting in those areas that are hot spots most at risk for certain conditions. And then trying to overlay some of those sensitivities. By combining the sensitivities and exposures, again, trying to identify those things that are most critical for us to then drill into and learn more about.

So, that takes us to the second level, on the ground. Once we have those hotspots identified, we have a general idea of where we need to be looking. We can then drill down into those resources that are in those locations to really get a good understanding for existing conditions, for the potential for response to future conditions, and develop approaches to build that resilience through maintenance.

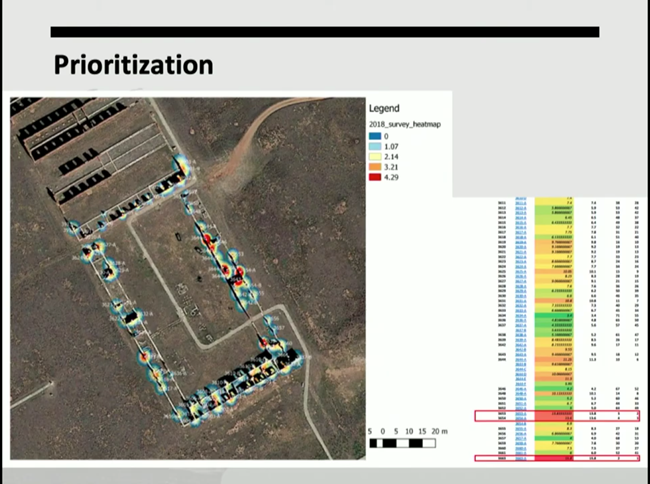

So, the project goals with the University of Pennsylvania is to develop a rapid risk assessment focused on site and materials, development of an approach to assessing risks and identifying priorities using the adobe walls at Fort Union as a case study. Again, the canary in the coal mine, right? Those resources that are most at risk, those most vulnerable. And then we intend to take the work and translate it to other parks and other resource types, focusing on significance, condition and threat. The idea getting us to the best return on money and time invested. Making those choices and prioritizing and then using a methodology of evidence-based phenomena. We want to monitor. Once we have a general idea of what's happening out there, what the conditions are, we then set up monitoring equipment so that we can see on the ground what's happening. It's not just based on assumption, it's based on evidence.

So, a couple of phases to the project. The first one, understanding behavior and deterioration as a system. Multi-scaler is everywhere, right? So, our projects are multi-scaler in that they start at the 30,000 foot level and go to the ground. But even in this project, they're looking at things at multiple scales. They're looking at things across the site, they're looking at individual walls, and then they're drilling down into material components. What are those conditions of that brick in that wall? Trying to target those locations and those features that are most at risk and need the most attention. The factors that are focused on are material and construction, orientation and exposure, previous treatments, because we all know that over time the treatments that you apply have an impact on how a resource survives or thrives through time, cyclic maintenance, and visitor impact. Lots of factors involved including management goals and funding.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

Once that's done, the data is compiled, and we go into a rapid prioritization. It's a heat map. Which are those areas based on that sort of complex list of factors that rise up the list. What are the reds, which are the most at risk, through sort of the greens and yellows? And then the decision is made as to which of those do you actually target first, is it the reds or are the reds already too far gone? Do you focus on the oranges and the yellows because you still have the ability to intervene before those resources are really damaged and beyond help.

And then the monitoring, right? Developing a protocol that can be shared across resources. It has to be efficient, it has to be cost effective, it has to be easy, right? And a lot of these projects really are about identifying approaches that are going to be simple, straightforward, easy to understand, and transferable. The factor is our repeatability, efficiency, costs, redundancy, simplicity. Again, we want to put something together that's easy for someone to use and understand. You don't need to be a specialist in any one thing or another to be able to read the results and understand what's going on, on your site.

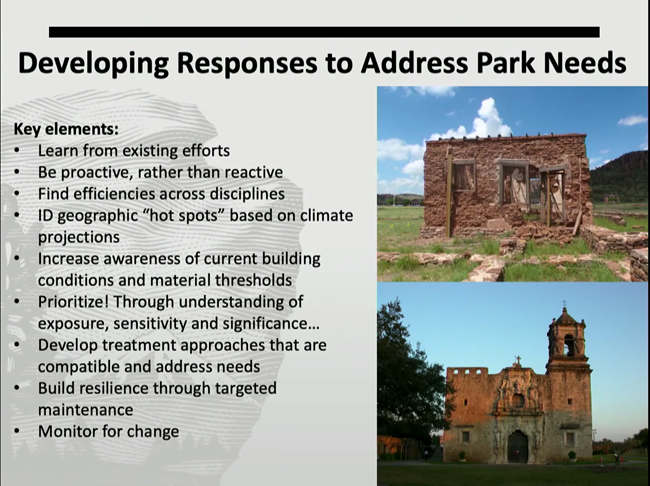

So again, to wrap up the projects, what is it that we've been trying to do over time in our program? What are the things that we've been seeing and what is our intent? We're trying to learn from existing efforts. We are not the first ones to do this. Work like this is going on across the country, around the world, and we're really trying to pick those things that are most relevant to the resources that we work with and bring them into our projects. Be proactive rather than reactive. We want to get to these things before the damage happens. If the damage happens, very often it's too late and we've lost integrity, we've lost the original material, and we're trying to preserve that original material. Identify those hot spots. As a regional program person, it's my job to advocate for a number of parks, not just one.

But how do I identify those parks and those resources that are most at risk that I can best advocate for them? And then within a park, how do you identify those resources within your geography that are the hotspots and require that advocacy?

Increase awareness of current building conditions and material thresholds. This is sort of a broader science issue. Current building conditions. How often are we able to get out and do condition assessments across entire landscapes with every resource? Not very often. We just don't have the capacity to do it. So again, it goes back to prioritization. If we know where the hotspots are, we know which resources we need to go back to more often than not to make sure we have updated conditions. The material thresholds is a conservation science issue. We need to be collecting all of the data that's already out there, whether it was collected for climate change studies or not.

How long does it take for an adobe block to melt out in the environment when it's impacted by water? I'm sure that study has been done many times over not related to climate change. But collecting all of that information so we have a better understanding of building materials. Prioritization, that's the key to everything. Figuring out what it is that we're going to save because we're not going to be able to save everything. Exposure, sensitivity, and significance overlaying all of those things to come up with that prioritized list.

Lauren Meyer, Vanishing Treasures Program, National Park Service

Develop treatment approaches that are compatible and address needs and those treatment approaches are going to have to change. Right? Again, buildings are built in a certain environment to withstand certain environmental conditions. Those environmental conditions are changing. Our treatments were directed to those environmental conditions. We have to change our approaches in some cases.

And then that build resilience through targeted maintenance. The more capable we are, the more able we are to maintain our resources, the better they'll be able to withstand changing environmental conditions. So, being targeted and making sure that we know where those priorities are so that we can invest ahead of things falling apart and then monitoring.

So, final thought because I think this is where talking about cultural landscapes and architecture, we s veer a little bit away from each other, I think, in that idea of managing for change. The idea of managing for change when you're talking about climate change comes directly out of our natural resources.

I found it really interesting, Susan [Dolan], listening to you talk about this as well and we've had conversations about this in the past, and Julie [McGilvrey] and I have had ... we used to sit next to each other in our office and argue back and forth about some of these things. For the built environment, most cultural resources do not have inherent adaptive capacity. They don't. They can't change on their own. It's not like species migration. Changes in vegetation communities. In order for a building, something that is not living to adapt, it's about us helping it.

Loss has extreme and immediate consequence, right? You lose that significant feature and it's gone, and you have to make a choice as to whether you're going to reconstruct it or you're going to leave it and let it go. And really, I think this is the case for our historic structures and archeological resources. We need to equate those high priority resources to endangered species and really focus on those resources and the needs of those resources. Because if we don't, and if we don't invest the time and money in their preservation, they will be gone, and with them, we lose our history, our culture, our traditions.

Thank you.

National Park Service

Speaker Biography

Lauren Meyer oversees the National Park Service’s (NPS) Vanishing Treasures (VT) Program, an effort that addresses the preservation needs of an outstanding collection of significant heritage architecture in the American west; perpetuates traditional building skills through training; and promotes connections between culturally associated communities and tribes and places of their heritage. In this position since October of 2014, Lauren works alongside an expert team to provide guidance, project assistance and historic preservation training to a diverse group of stakeholders. With the NPS since 2002, her focus areas include the conservation of archeological sites in the Southwestern U.S. and the development of multi-disciplinary approaches to cultural resource management. Lauren has a BA in Archaeological Studies from Boston University, a MS in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania, and an Advanced Certificate in Architectural Conservation and Site Management from the University of Pennsylvania.