Last updated: February 26, 2025

Article

Luther Jotham: A Journey for Country and Community

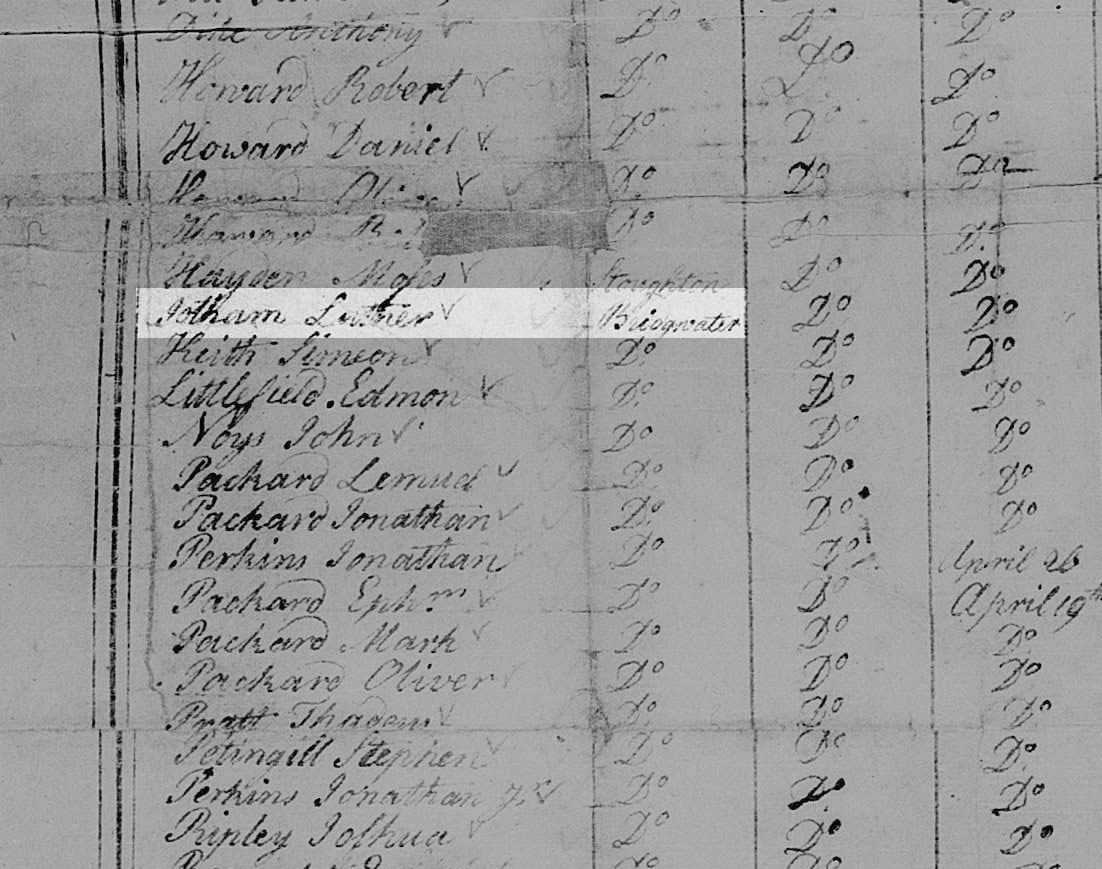

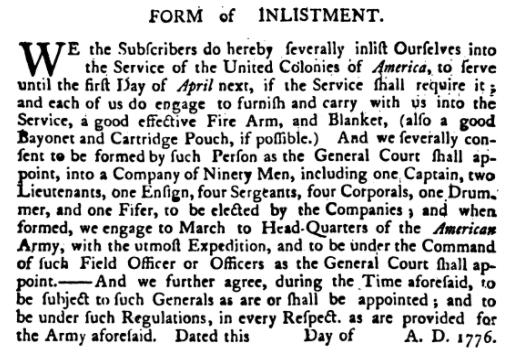

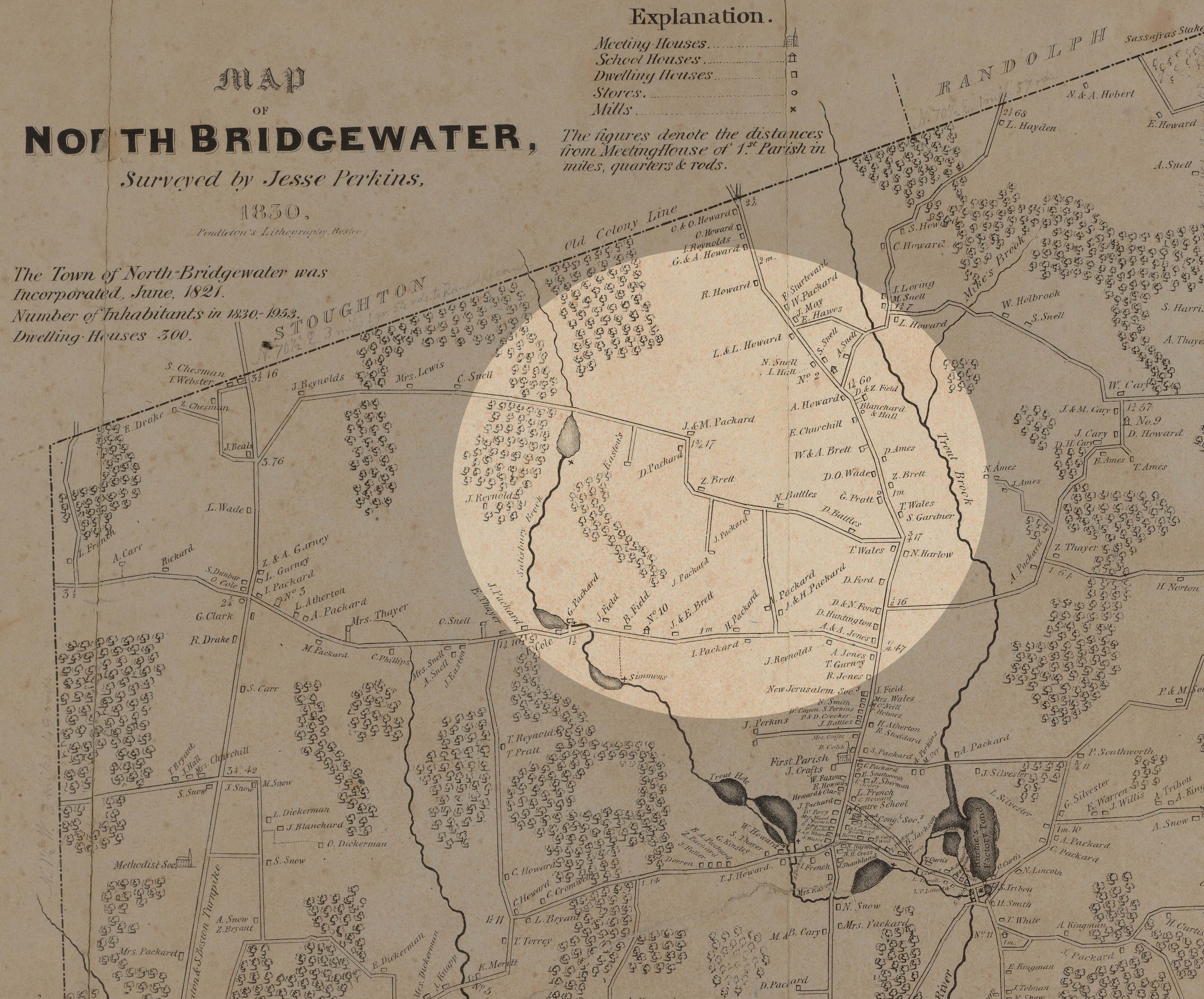

On paper, Luther Jotham's Revolutionary War service record reads like a typical service record of a Minute Man from rural Massachusetts in 1775. Volunteering to serve at a minute's notice in case of an emergency, Jotham trained weekly with his neighbors in battle tactics. On April 19, 1775, when the alarm sounded at Lexington and Concord, Jotham joined his company of Bridgewater Minute Men in defense of their community.

Luther Jotham, however, differed from most Minute Men. As a free man of color, Massachusetts law excluded men like Jotham from participating in militia training days in peacetime. Yet in the midst of a looming emergency, he volunteered to protect his neighbors. Following the April 19 alarm, Jotham ultimately signed up to serve on four different occasions during the Revolutionary War.

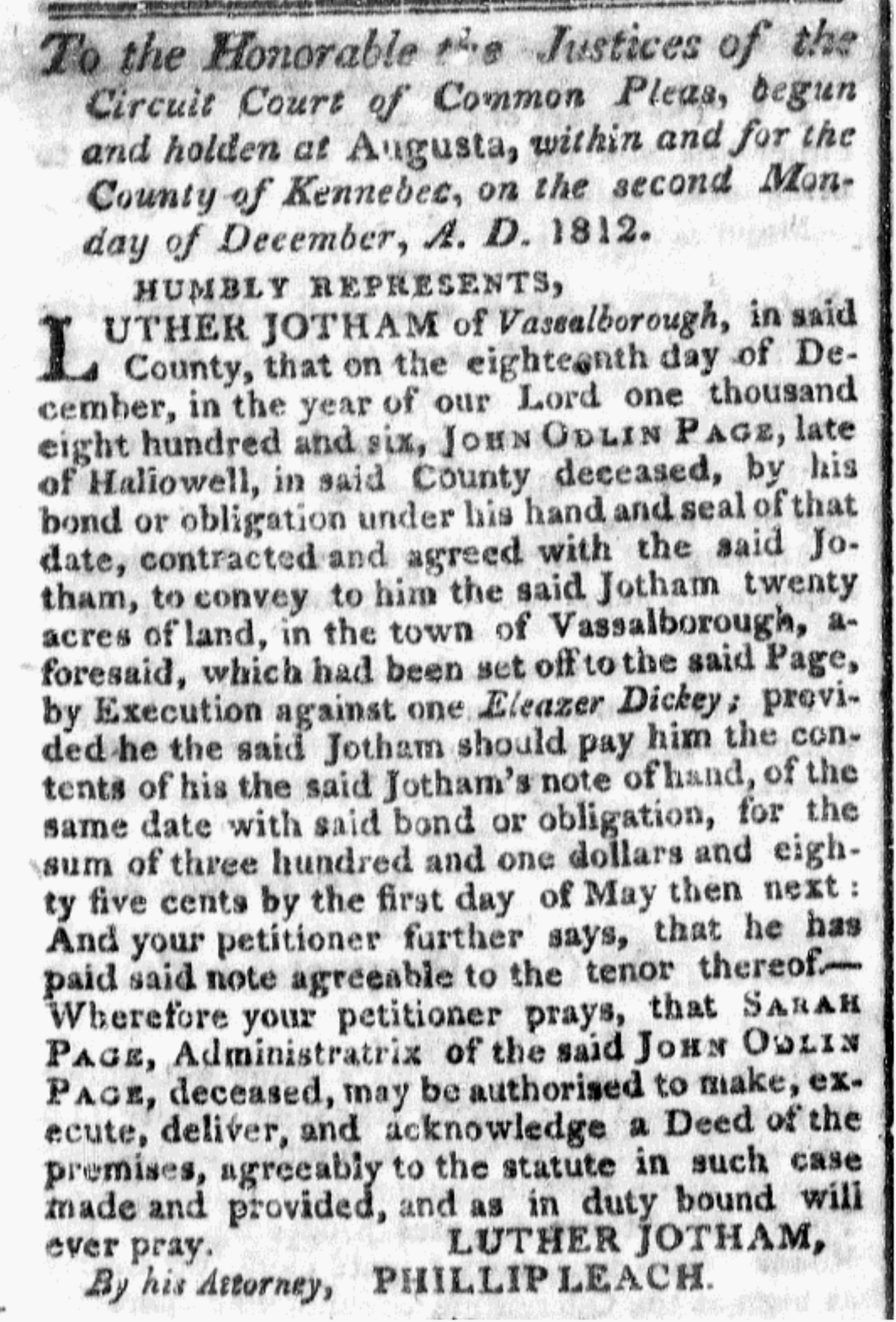

When he returned to Bridgewater, Jotham worked to establish himself as a yeoman—a man who farmed his own land. Eventually he moved to Maine to better establish himself and his family as farmers. Though able to support his family for some time, like so many other Revolutionary War veterans, Jotham later struggled to make ends meet in the country he helped fight for. Turning to the United States for a pension, his application gives us a glimpse into the life of one patriot of color in his struggle for community, country, and financial independence.

Explore the story map below to learn about Luther Jotham’s life story. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Contributed by Danielle Rose, Digital Public History Intern

Footnotes:

[1] Middleborough had a Black population of less than one percent during the 1750s. J.H. Benton, Jr., Early Census Making in Massachusetts 1643-1765 with a Reproduction of The Lost Census of 1765 and Document Relating Thereto (Boston: Charles E. Goodspeed, 1905), 91. Via Familysearch.org.

[2] “The Lives of Individual African Americans in America before 1783,” Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/features/endofslavery/life.

[3] “The Militia and Minute Men of 1775,” Minute Man National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/the-militia-and-minute-men-of-1775.htm.

[4] John Hannigan, “Independence or Freedom,” Minute Man National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/john-hannigan-patriots-of-color-paper-5.htm.

[5] Justin Winsor, History of the Town of Duxbury, Massachusetts: With Genealogical Registers (Boston: Crosby & Nichols, 1849), 127. Archive.org.

[6] James Thacher, History of the Town of Plymouth, from its first settlement in 1620 to the present time: with a concise history of the aborigines of New England and their wars with the English (Boston: Marsh, Capen & Lyon, 1835), 207. Archive.org.

[7] Bradford Kingman, History of North Bridgewater, Plymouth County, Massachusetts: From its first settlement to the present time, with family registers (Boston: 1866), 146. Archive.org.

[8] A Muster Roll of Capt. Josiah Hayden’s Company in regiment of foot in the continental army Encampt at Roxbury, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 69, Image 15, October 6, 1775, via FamilySearch.org. Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 39, via Fold3.com.

[9] Francis S. Drake, The town of Roxbury: its memorable persons and places, its history and antiquities, with numerous illustrations of its old landmarks and noted personages (Roxbury: 1878), 80. Archive.org.

[10] “To George Washington from John Hancock, 8 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0465. “General Orders, 1 January 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0001.

[11] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 37 and 39, via Fold3.com. Payment Roll of Capt. Elisha Mitchell’s Company in Col. Cary’s Regiment, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 36, Image 242, April 2, 1776, via FamilySearch.org.

[12] Mary Stockwell, “Siege of Boston,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/siege-of-boston/.

[13] David G. McCullough, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2006), 93. Archive.org. “Dorchester Heights,” Boston National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/dohe.htm.

[14] “General Orders, 21 March 1776,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0372.

[15] Roll for Capt. James Allen’s Company, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 55, Image 395, August 1776, via FamilySearch.org.

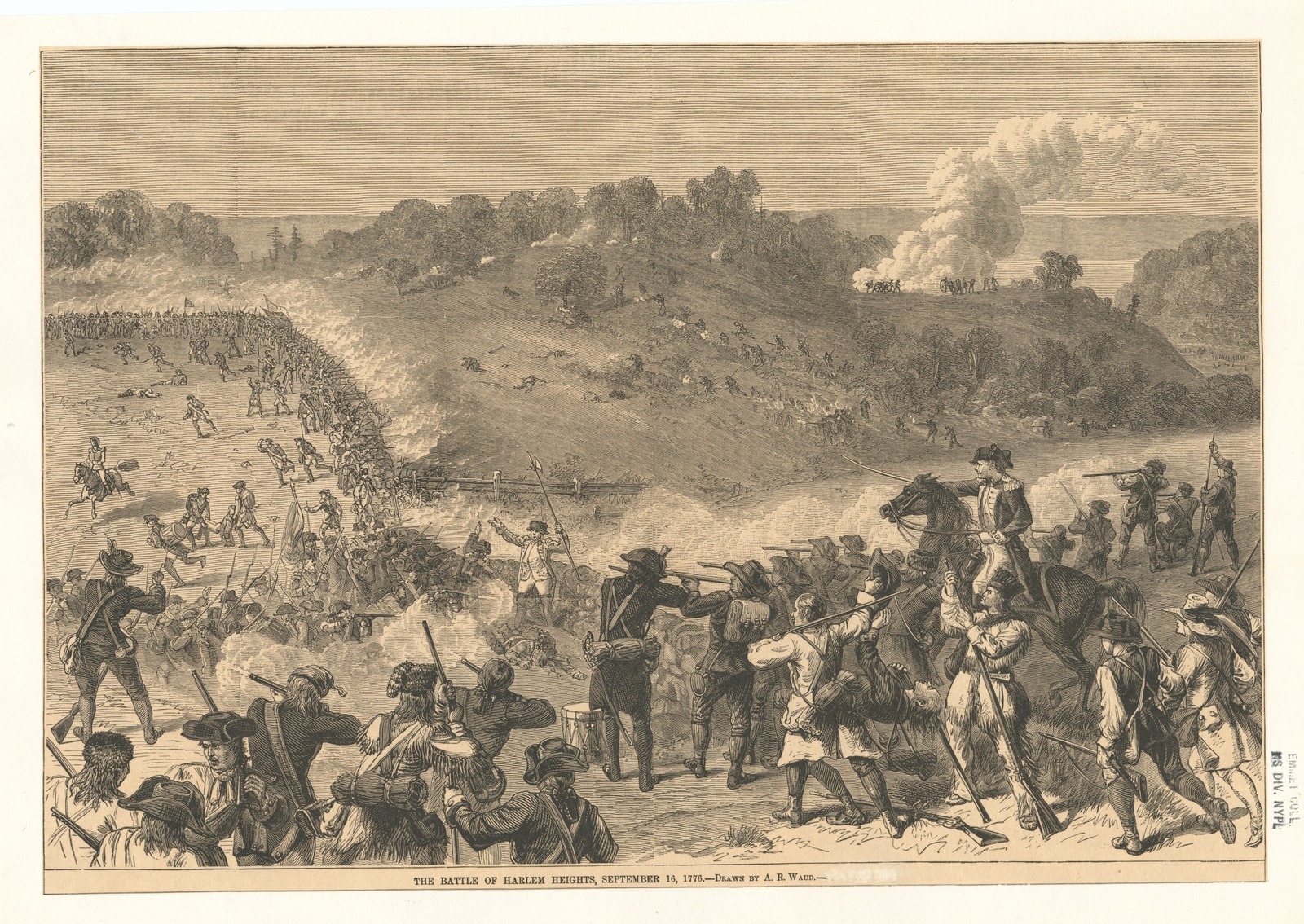

[16] Harry Schenawolf, “Battle of Harlem Heights Sept. 16, 1776: Americans Gave the British a Good Drubbing,” Revolutionary War Journal, January 15, 2014. https://www.revolutionarywarjournal.com/battle-of-harlem-heights/.

[17] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 23, via Fold3.com.

[18] McCullough, 1776, 219.

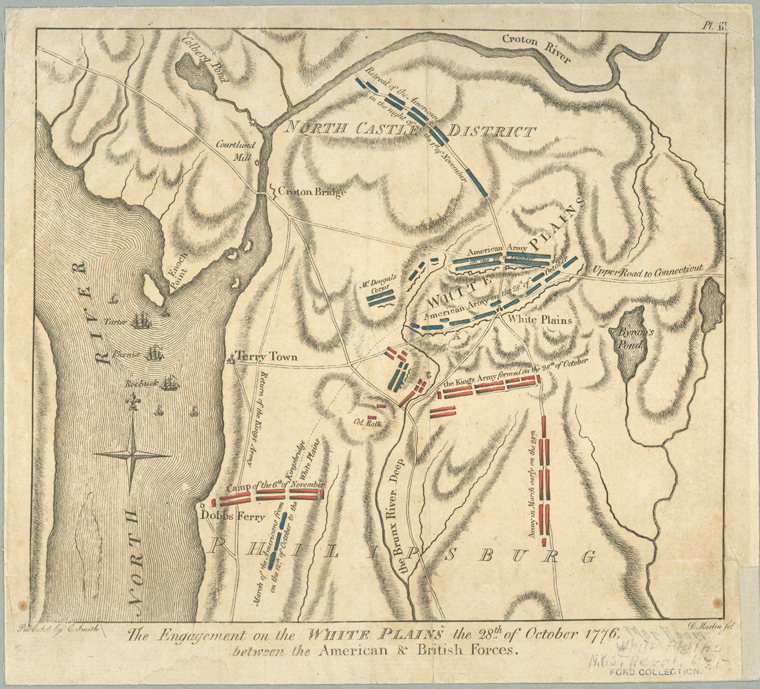

[19] McCullough, 1776, 232-234; Joseph C. Scott, “Battle of White Plains,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/battle-of-white-plains/.

[20] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 23, via Fold3.com.

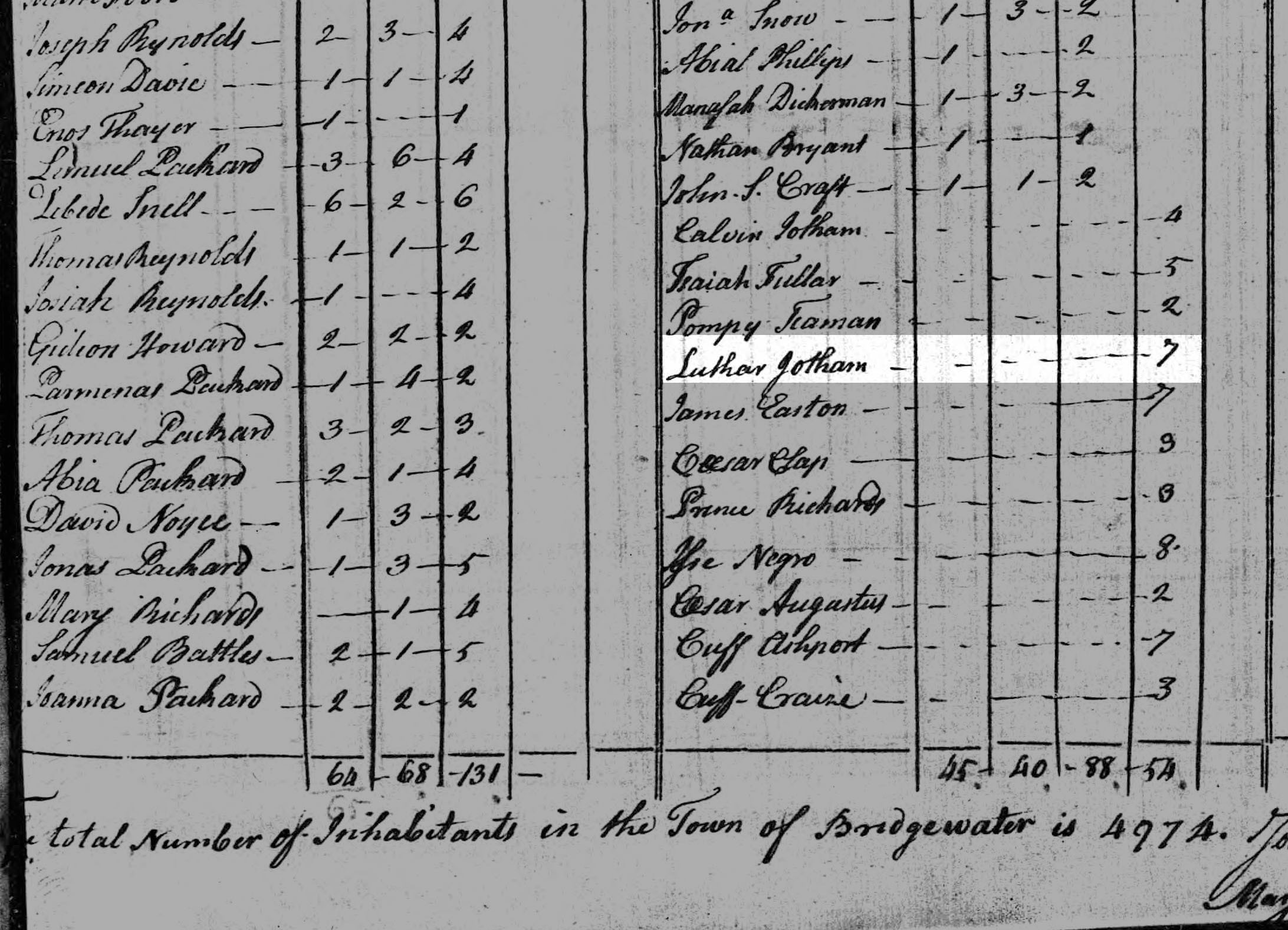

[21] Massachusetts Office of the Secretary of State, Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War: A compilation from the archives (Boston: Wright and Potter Printing Co., State Printers, 1896), Vol. 8, 1008. Via Archive.org. A Pay Roll of Capt. Nathan Snow’s Company in Col. Hawes Reg on the Secret Expedition in October 1777, Muster/Payrolls and Various Papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War, Vol. 22, Image 342, August 1776, via FamilySearch.org.

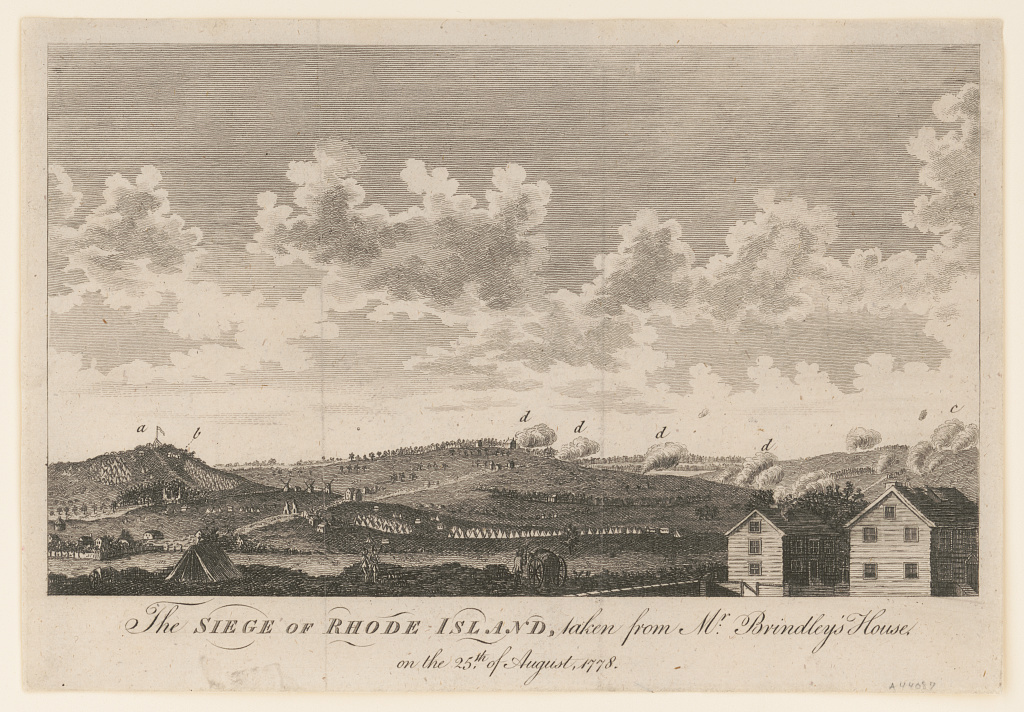

[22] Rhode Island Historical Society, Proceedings of the Rhode Island Historical Society (Providence: 1872), 89, Archive.org.

[23] Ibid. “The Battle of Rhode Island,” Tiverton Historical Society, http://www.tivertonhistorical.org/tiverton-stories/the-battle-of-rhode-island/.

[24] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 32, via Fold3.com.

[25] According to property records, Jotham continued to purchase and sell several acres of land in Bridgewater over the next two decades. Luther Jotham Deed, Book 65, page 230, August 31, 1786. Accessed via Plymouth County Registry of Deeds.

[26] Luther Jotham Deed, Book 66, page 252, June 12, 1787. Accessed via Plymouth County Registry of Deeds.

[27] Thomas Packard v. Luther Jotham, Plymouth County, MA: Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859. Vol. 10, page 90. Via AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Luther Jotham Dis Exon, Book 68, page 113, May 22, 1788. Accessed via Plymouth County Registry of Deeds.

[28] Luther Jotham Deed, Book 88, page 270, February 23, 1801. Accessed via Plymouth County Registry of Deeds.

[29] People of color made up only 1.5% of Bridgewater’s entire population. George R. Price, “The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753-1935” (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers, page viii. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598.

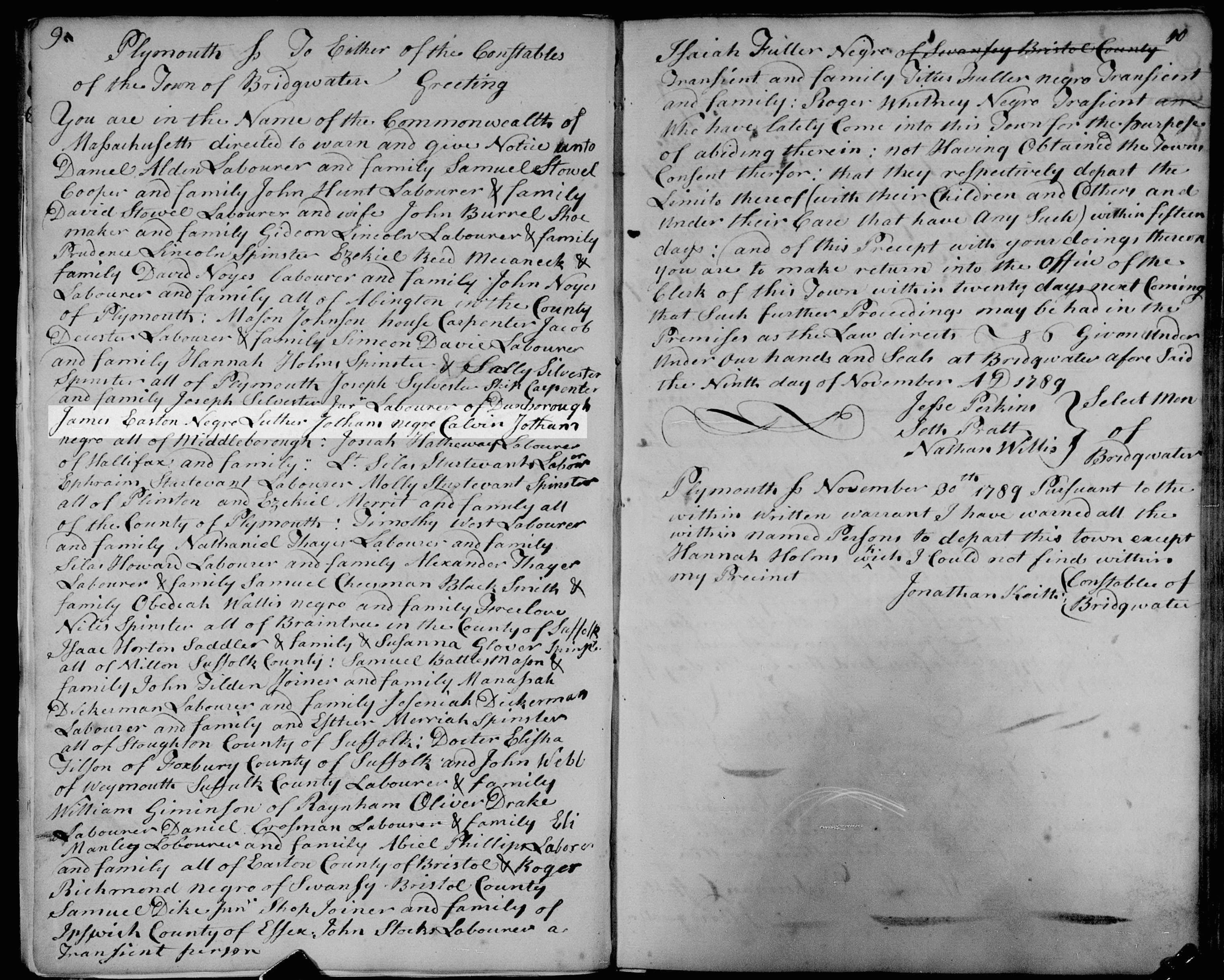

[30] Bridgewater Massachusetts Selectmen’s Records, 1703-1863, 9-10. Courtesy of the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

[31] Josiah Henry Benton, Warning out in New England 1656-1817 (Boston: W.B. Clarke Company, 1911), 55. Archive.org. Sheilagh Doerfler, "Warnings Out," Vita Brevis, June 20, 2017, https://vitabrevis.americanancestors.org/2017/06/warnings-out/.

[32] 1790 U.S. Census, Bridgewater, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, digital image s.v. “Luther Jotham,” via AncestryLibrary.com. 1800 U.S. Census, Bridgewater, Plymouth County, Massachusetts, digital image s.v. “Luther Jotham,” via AncestryLibrary.com.

[33] Price, “The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts,” 52, 81.

[34] Ibid, 49.

[35] William Cooper Nell, The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution: With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1855), 33. Archive.org

[36] Kingman, History of North Bridgewater, 318.

[37] Kennebec County, Maine, Record of Deeds 1817-1820, Vol. 28, page 215. Via Familysearch.org.

[38] Prior to this, only men disabled during service qualified for a pension. The 1818 Act expanded the lifetime pension to all men who served in the Continental Army or Navy and showed the need for financial assistance. Michael Barbieri, “Good and Sufficient Testimony: The Development of the Revolutionary War Pension Plan,” Journal of the American Revolution (August 26, 2021), https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/08/good-and-sufficient-testimony-the-development-of-the-revolutionary-war-pension-plan/.

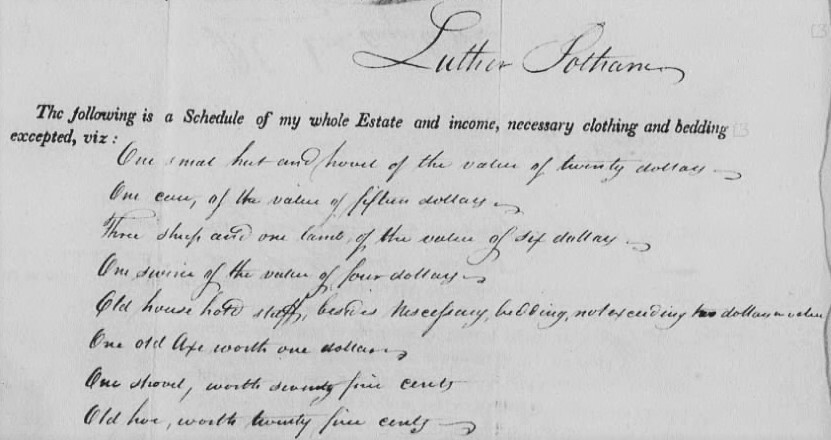

[39] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 18, via Fold3.com.

[40] Ibid, page 18.

[41] Ibid, page 55.

[42] Ibid, page 32.

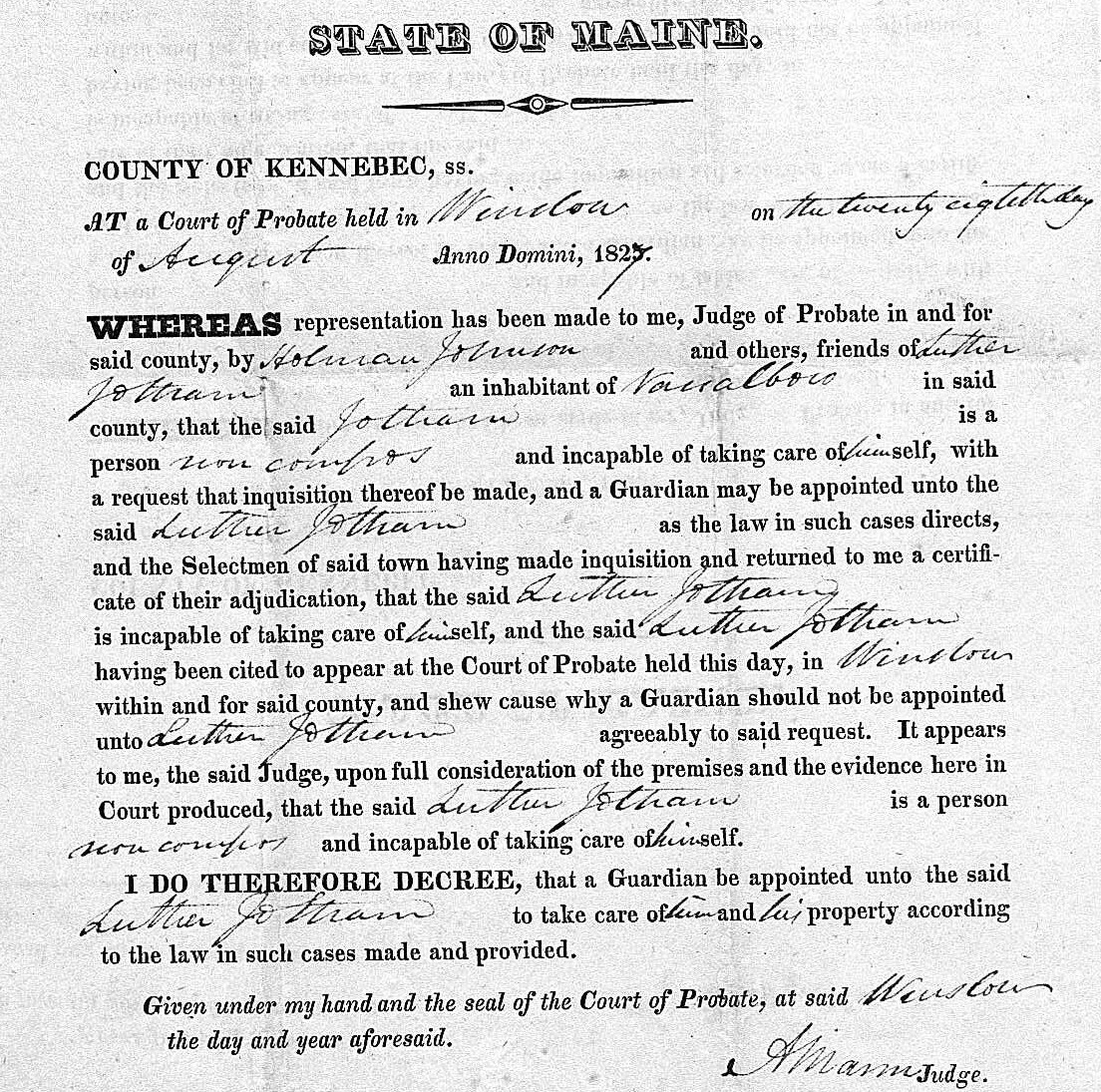

[43] Kennebec County, Maine, Probate Estate Files 1779-1915, File no. J5, via Familysearch.org.

[44] David Wagner, “Poor Relief and the Almshouse,” Social Welfare History Project, https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/issues/poor-relief-almshouse/.

[45] Find A Grave, Luther Jotham (1751-1832), Memorial no. 174230453, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/174230453/luther-jotham.

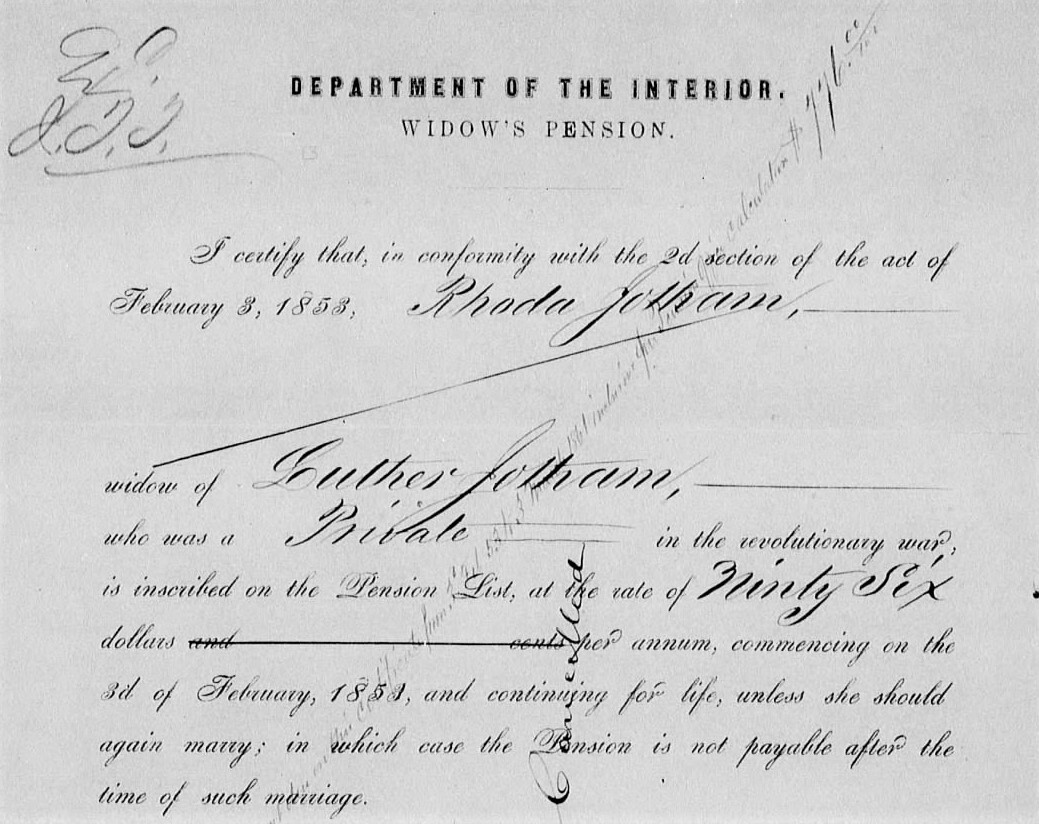

[46] Luther Jotham, Pension No. W. 9911, Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files. NARA M804, page 5, via Fold3.com.

[47] Ibid, page 28.