Part of a series of articles titled Copper Connections.

Previous: Why Copper?

Article

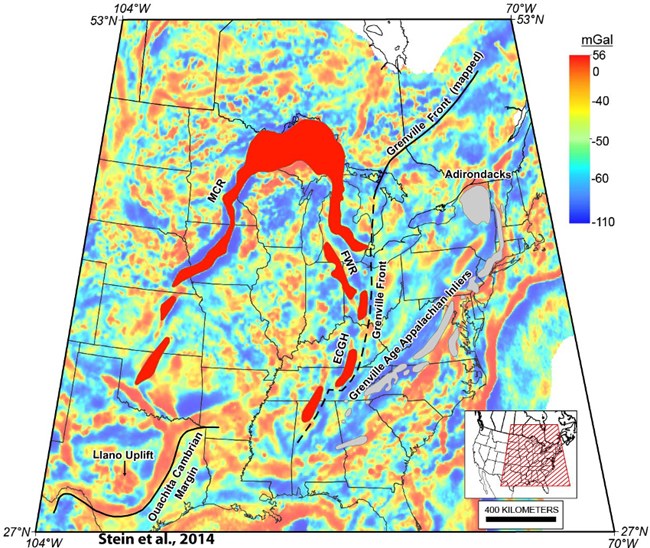

Stein, C. A., S. Stein, M. Merino, G. Randy Keller, L. M. Flesch, and D. M. Jurdy (2014), Was the Mid-Continent Rift part of a successful seafloor-spreading episode?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 41(5), 1465-1470, doi:10.1002/2013GL059176, 2014.

NPS image

NPS photo

![[2:42 PM] Clark, Nicholas J Cross sectional illustration showing rock types. Volcanic and sedimentary rocks form a bowl shape, with Isle Royale and the Keweenaw being opposite rims of the bowl. A thin sky-blue band fills the top of the bowl.](/articles/000/images/KEWE-Cross-sectional-55555555555.png?maxwidth=1300&autorotate=false)

Part of a series of articles titled Copper Connections.

Previous: Why Copper?

Last updated: March 6, 2024