Last updated: March 20, 2023

Article

Keweenaw Industrial Landscapes

Overview

A Landscape Shaped Through Centuries of Human Activity and Settlement

The Keweenaw Peninsula in Michigan contains the “world’s largest concentration of native copper” (Cannon and Nicholson 1), and this resource has shaped its landscape. Copper has a long history of use in a variety of applications, from current-day electrical wiring to tools made millennia ago. Early Indigenous peoples mined copper on the Keweenaw Peninsula, and for thousands of years, Lake Superior tribes exchanged it through vast trade networks that crossed much of North America. These groups found the malleability of copper suitable for fabricating utilitarian objects like hooks, knives, and beads, as well as more ornamental items.

European-American mining started in the early 1840s, and extensive industrial mining operations quickly and drastically altered the landscape. Around five billion kilograms of copper were extracted from 1845 to 1968 (Cannon and Nicholson 1). During this period, the American transportation, defense, and technology industries relied on Keweenaw copper.

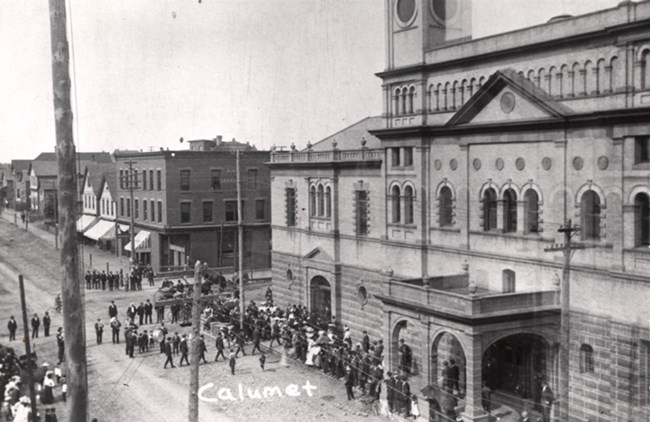

The Keweenaw Peninsula, part of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, extends into Lake Superior and features a highland running its length. The highland, the Lake Superior Copper Range, was the location of several nationally significant mining company ventures and is the current location of Keweenaw National Historical Park. The park contains two units, Quincy and Calumet, that include a multitude of cultural resources related to the industrial copper mining industry over the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Indigenous Landscape Patterns

Much of the landscape associated with Indigenous mining activities has been destroyed as a result of the intensity of the industrial mining practices that began in the mid-19th century. Indigenous people occupied the Lake Superior basin over 8,000 years BCE. They hunted large mammals, such as caribou, bison, elk, and moose, and likely were nomadic. Thousands of years later, the Keweenaw would be covered with a northern coniferous forest, but the lack of dense vegetation in the post-glacial landscape enabled people to see and locate copper outcroppings more easily. People soon began working with copper, giving rise to what is now called the "Old Copper Culture,” which commenced around 4,000 BCE. During this time, early miners modified the landscape by extracting copper from the earth for making practical and ornamental items, as well as for trade with other groups of people. Thousands of mining pits followed copper lodes, ranging from a few feet deep to more than thirty feet deep, and to 120 feet in diameter.

The miners developed a process of extraction that involved heating rock with fire and pouring water over it to initiate cracking of the encasing rock. Early miners used hammerstones – a handheld stone tool – to extract the copper from surrounding bedrock. Some of the hammers weighed up to 40 pounds. Other tools included wooden shovels, baskets, and leather bags.

Metalworkers then used cold hammering and annealing (heating to make the copper more malleable) to form weapons and ornamental items. These fabricated works and raw copper were traded in extensive networks between 1000 and 1450 CE. Demand for copper grew and waned over time. By the late 1400s, interest in copper as a utilitarian material had declined. Some scholars speculate that the malleability of copper and corresponding lack of durability reduced its desirability.

By the late 15th century, the Ojibwa, a member of the Anishinaabe people (which also includes the Odawa and Potawatomie), were the most prominent group in the area. They organized their communities into individual bands on both sides of Lake Superior. The Ojibwa way of life related strongly with the seasons: in the warm months they fished, and grew and stored food, and relied on hunting in the winter. They harvested wild rice and maple sugar and cultivated blueberries, among other fruits and vegetables. Copper held deep spiritual importance for the Ojibwa and was considered a sacred gift.

In the mid-1600s, the Ojibwa, historically mobile bands, began establishing permanent villages in the Lake Superior basin and engaging in the fur trade, allied with the French. The Ojibwa were valuable guides and trapped fur-bearing animals like beavers. They achieved economic success in trade, but soon experienced clashes with the Haudenosaunee, who had allied with the British and were now moving west to seek the resources of the peninsula. The Ojibwa managed to hold their territory into the mid-1800s.

Industrial Landscape Formation

As the population of fur-bearing animals declined, interest in other Keweenaw resources, specifically copper, expanded. The US government recognized copper's value to the growing European-American population and domestic economy. During the Industrial Revolution, the demand for copper grew exponentially, especially for use in telecommunications and electrical power transmission.

In the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe, the Ojibwa ceded their mineral rights while retaining the right to fish, hunt, and gather on the Keweenaw Peninsula. Ultimately, the retained rights were violated as copper miners overtook the area. Fort Wilkins, located near the top of the Keweenaw Peninsula and where most arrivals disembarked, was established in 1844 to defend miners from the Ojibwa, although the fort was never used in defense.

As copper prospectors and entrepreneurs occupied the peninsula, the landscape quickly began to change. They cleared small areas, and settlements soon sprung up between the dense groves of trees. An 1845 survey of the peninsula indicated forests contained sugar maple, birch, fir, oak, and white pine. Other land types included swamps and marshlands. The Portage Lake waterway, used by the Ojibwa and earlier Indigenous peoples, provided passage across nearly the whole width of the peninsula. By the 1870s, the portage for which the waterway was named had been removed by dredging, and large ships docked directly at the waterfront communities of Houghton and Hancock.

Mining companies acquired swaths of property and made efforts to conduct large scale operations. Companies were drawn first to mass copper deposits, where copper formed into giant boulders, thinking they would be the most profitable. They soon encountered challenges to this approach. It was difficult to locate profitable copper masses, with some simply too large and too labor-intensive to bring to the surface in an economic matter. There was also a lack of government oversight in the lease-permitting system, and some companies discovered they held mineral rights to the same property.

Development of Quincy and Calumet

Conclusion

The cultural landscapes associated with the Quincy and Calumet units reference the nation’s extensive mining history across millennia. Although many of the cultural landscapes related to Indigenous peoples’ mining activities and lifeways were lost through the extensive industrial manipulation of the landscape, the archeological, ethnographic, historic record, and descendant community confirms the presence of these places.

NPS / Keweenaw National Historical Park

Park boundaries now encompass much of the industrial landscapes shaped by the Quincy Mining Company and the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company (C&H). Each unit reflects the character of 19th century industrial landscapes within living communities. Together they illustrate many of the environmental impacts of copper mining, refining, and production. In addition to the earth displacement associated with the mining itself—once most evident in massive poor rock piles (now recognized as a valuable construction material and quickly disappearing) that mark the locations of former shafts—the operations resulted in topographic manipulation, deforestation, and water pollution. The landscapes contained within the park units were valued and exploited for their physical resources without understanding and attentiveness to the environmental consequences.

The landscapes in both park units also provide local evidence of national technological and social changes that occurred from the late 1800s into the mid-1900s. Housing and community amenities changed over time in response to the needs and wants of the workers. Both Quincy and C&H built houses and leased land to organize their property and attract workers. The Calumet unit specifically highlights historic planning efforts to accomplish separate use zones and establish community spaces, such as Agassiz Park.

The industrial, residential, and commercial buildings that remain within both Calumet and Quincy help visitors understand the historical significance of these landscapes. The NPS, along with a variety of partners, including other levels of government, non-profits, and private property owners, own historic resources within both park units, allowing a collaborative approach to the preservation and interpretation of these nationally significant landscapes.

-

Cannon, William F., and Suzanne W. Nicholson. Geologic map of the Keweenaw Peninsula and adjacent area, Michigan. US Geological Survey, US Department of the Interior, 2001.

-

Quincy Mine Historic Landscape Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment

-

Calumet Unit Historic Landscape Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment