Last updated: September 5, 2024

Article

Quincy Unit Cultural Landscapes

NPS / Dan Johnson

Development of the Quincy Unit

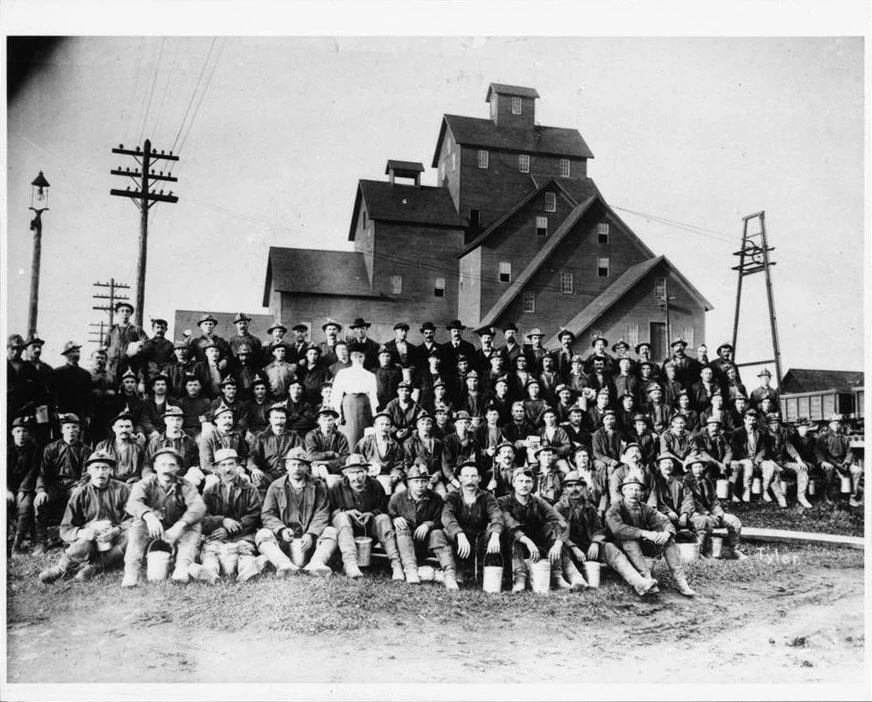

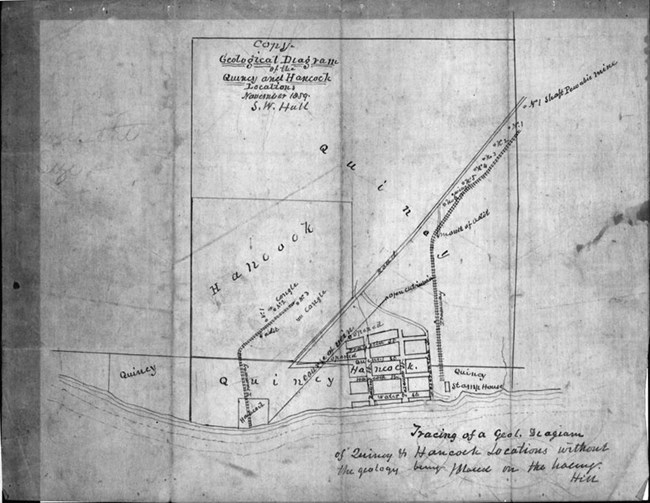

The Quincy Mining Company was formed as a result of two mineral claims to the same property. The Portage Mining Company and Northwestern Mining Company resolved the conflict by merging into a single entity, and the Quincy Mining Company was incorporated in 1848. Unlike Calumet, the mine at Quincy is separate from the village of Hancock to the south. The mine was located on a bluff overlooking the Portage Waterway, while its stamp mills and smelter would, in time, be built along the shoreline below. The landscape contains seven Quincy mine shafts, associated mining and industrial surface works, features and ruins, several company housing locations, circulation routes and paths, and remnant administrative and service buildings and managers’ residences.

Early on, Quincy workers attempted to locate a copper-bearing fissure lode by digging exploratory trenches. They sank shafts – deep holes into the lode, with ladders for miners to enter and exit the mine – at promising sites and began adding infrastructure.

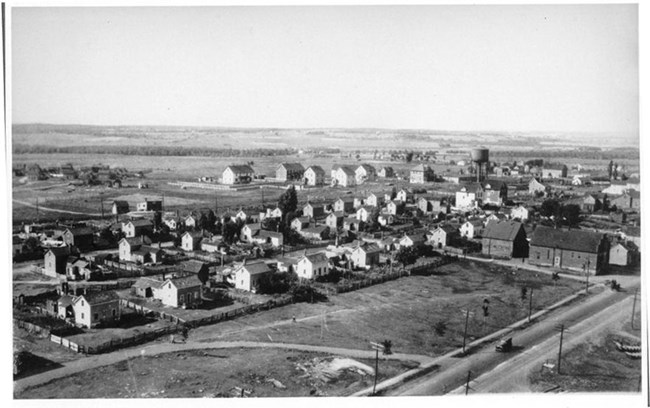

Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress

The Quincy Mining Company layout demonstrated a prioritization of functionality over aesthetics. The location of underground copper lodes dictated the position of mine shafts, and also influenced the placement of other elements of the surface plant, including supply shops, trams and railroads for transporting copper, and other structures. The mine’s location next to a steep bluff overlooking the Portage Waterway also dictated the location of company housing. Log homes constructed on the hillside provided housing for workers. Other early community structures included a blacksmith shop, carpenter shop, saw mill, and store house. These structures were characterized by vernacular architecture (built in a style and construction that reflect the everyday lives of people), use of local materials, and lack of ornamentation. Foot, horse, and wagon traffic created informal, wide paths connecting the industrial structures with the nearby town and housing locations.

Quincy was fortunate enough to have built its mine atop two lodes on Quincy Hill: the Quincy lode and the Pewabic lode. The Quincy lode was located in 1854 and abandoned the same year. The Pewabic lode, located in 1855, was so profitable it eventually earned Quincy the nickname of “Old Reliable” for paying consistent dividends. Unlike mass (fissure) lodes, Quincy mined amygdaloid deposits, where copper formed as smaller specks and pieces in the rock. This material was more economical to mine because after being drilled and blasted, rock could be brought to the surface more easily than mass copper, and then stamped to liberate the copper within the rock matrix. The Pewabic lode was discovered through exploration of ancient Indigenous mines and a discovery on an adjacent mining company’s location. The company quickly increased operations on the Pewabic lode by sinking additional shafts and building a shafthouse for each one. These provided protection for the open mine shaft and was where rock was hoisted.

Early mining operations used calcining, which involved manually removing copper-bearing rock from underground via the shafthouse, sending it to a rockhouse for classification and initial processing, and then further separating the copper from the rock. Large pieces of copper rock were calcined, a process of rapidly heating and cooling to crack as much of the rock from the copper as possible. After refining the copper and transporting it to the dock, it was shipped to Detroit to be smelted.

Technological improvements that were implemented at Quincy enabled more efficient extraction. In 1858, portable steam engines replaced whims, which were powered by human and animal labor in hoisting minerals from the shafts. While these engines reduced the labor required in extraction, they required cordwood fuel and water to operate. The land around Quincy was soon clear-cut and water was drawn up the steep bluff from Portage Lake. In the same year, the addition of a timber-framed stamp mill increased the operation’s processing power through the mechanized crushing of rock and direct disposal of tailings, known locally as stamp sand, into Portage Lake.

Historic American Engineering Record, Library of Congress

In conjunction with the increased industrial capabilities, Quincy required more employees and the means to support and retain them. Around 1860, the company leased farmland to workers and added more housing, including wood-framed tenement houses. The houses typically consisted of a wood frame and garden plot. A hospital, church, and school were added during the same period. A community club house and new water system were built between 1915 and 1918. Milling operations were relocated to the shore of Torch Lake after stamp sands began impeding navigation through the Portage Canal in the 1890s.

By the 1880s, Quincy produced twenty percent of the world’s copper supply, but it could not carry its success far into the 1900s. By the 1890s it had built an additional stamp mill as well as its own smelter, but Quincy’s development and success reached a pinnacle in 1905. Soon after, a mine collapse and a worker strike that rocked the district between 1913 and 1914 contributed to operational difficulties. Copper demand rose in response to the start of World War I but fell by 1920 and war’s end. Quincy also found itself unable to compete with newer mines to the west, which had lower production costs and higher pay that attracted workers. In 1931, Quincy closed its deepest mine. It reopened briefly in 1937, for World War II production, before closing permanently in 1945.

NPS / Keweenaw National Historical Park

Quick Facts

-

Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Site

-

National Register Significance Level: National

-

National Register Significance Criteria: A

-

Period of Significance: 1846-1931

-

National Historic Landmark District