Part of a series of articles titled Remembering John Brown.

Article

To Secede or Not To Secede: John Brown and the Election of 1860

As the divisive election of 1860 approached, people across the nation were still processing and reacting to John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Slave insurrections were not a new concept; and slave revolts represented a slave holder’s worst nightmare. The events at Harpers Ferry, taking place almost one year before the election, provided fire-eaters like Edmund Ruffin the leverage “to stir the sluggish blood of the South.”[1] After the raid, Ruffin quickly made his way to Charles Town, Virginia, and joined the Virginia Military Institute Cadets for a single day in order to watch Brown’s execution.[2] He quickly began to write and distribute his thoughts about Brown. Ruffin even went so far as to send one of the then infamous pikes to the governor of every slave state (excluding Delaware). He had them each engraved with the words “sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern Brethren,” and sent them with a written request that the pike be displayed “as abiding & impressive evidence of the fanatical hatred borne by the dominant northern party to the institutions & the people of the Southern States.”[3] Other secessionists, including William Yancey of Alabama joined Ruffin in his quest to shape public opinion of Brown. While speaking in Washington just months before the election, he implored voters to think of the actions of John Brown when they cast their ballot in November:

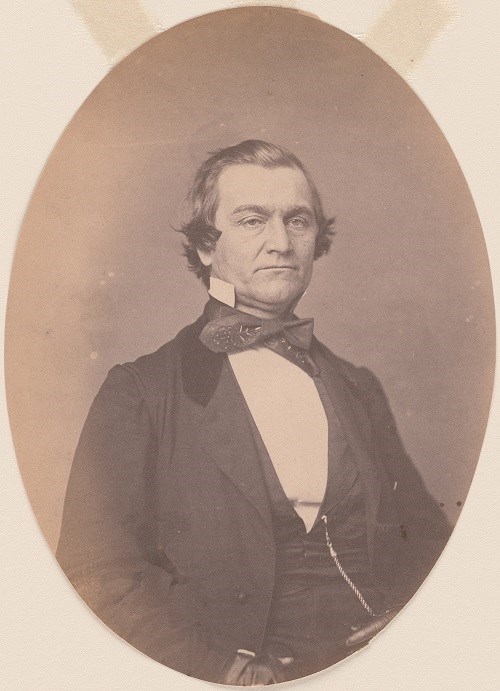

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

“Suppose that [Republican] party gets into power; suppose another John Brown raid takes place in a frontier State; suppose ‘Sharp’s Rifles’ and pikes and bowie knives, and all the other implements of warfare are brought to bear upon an inoffensive, peaceable, and unfortunate people...where will then be a force of United States marines to check that band?...Where will then be our peace, where will be our safety, when these people are instigated to insurrection, when men are prowling about throughout the whole country, knowing that they are protected by an administration which says that by the Constitution freedom is guaranteed to every individual on the face of the earth?”[4]

Secessionists worked in the weeks and months leading up to the election making sure that they shared their “Southern perspective." Their rhetoric surrounding John Brown inspired fear, leading some to believe that Brown represented Northern abolition sentiment. Following the election of Lincoln, slaveholders feared the second coming of John Brown. Southerners reacted in horror as they reflected on the ways Northern abolitionists like Ralph Waldo Emerson or Brown’s ‘Secret Six’ canonized Brown as a Saint and condoned “employing the persuasion of force.”[5]

Although Brown had Northern support from more radical and militant abolitionists, a separate faction of Northerners quickly distanced themselves from this fear-based rhetoric and encouraged compromise. After the election, one Philadelphia newspaper argued “... if a JOHN BROWN could be thrown into every Harper’s Ferry district in that section, backed not by eighteen, but by eighteen hundred men...we believe there would be an instantaneous exodus of the good men of all parties in the North and the Northwest to protect their countrymen in the South, and to crush out their spoilers.”[6] Boston-based Unionists argued that they were being mis-represented in the press, “it would be as unjust to charge the aggregate South with the design of reviving the African slave trade, as it would be to charge the aggregate North with the approval of John Brown.”[7] Some urged their peers to refrain from any language or action that could inspire states to secede; but others knew there was nothing else they could do. Brown’s assertion, “that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood,” proved prophetic.[8]

Sources

[1] Edmund Ruffin, quoted in John Stauffer, The Tribunal: Responses to John Brown and the Harpers Ferry Raid (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2012), p. xlii

[2] William K. Scarborough, “Propagandists for Secession: Edmund Ruffin of Virginia and Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine , July-October 2011, Vol. 112, No. 3/4, [Why They Seceded: Understanding the Civil War in South Carolina After 150 Years] (July-October2011), p. 131

[3] Scarborough, “Propagandists for Secession,” p. 132

[4] “Extract of a Speech of Hon. Wm. L. Yancey, at the Serenade Given to Him in Washton. Friday Night, September 21, 1860,” Bangor Daily Journal (Bangor, ME), October 1, 1860, p. 2.

[5] “Important Proceedings in Georgia,” New York Herald, November 16, 1860;

“The Issue,” The Yorkville Enquirer, November 15, 1860.

[6] “A Union Appeal,” Press (Philadelphia, PA), November 12, 1860, p.1.

[7] “Misrepresentation of the South,” New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette, December 12, 1860, p. 2. Quoting an article from the Boston Courier.

[8] “John Brown,” National Park Service, Last Updated March 20, 2018. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/people/john-brown.htm

Last updated: October 20, 2020