Part of a series of articles titled Whose Story is History? The Diverse History of Grand Canyon.

Article

Japanese Americans at Grand Canyon - Bellboys and WWII Heroes

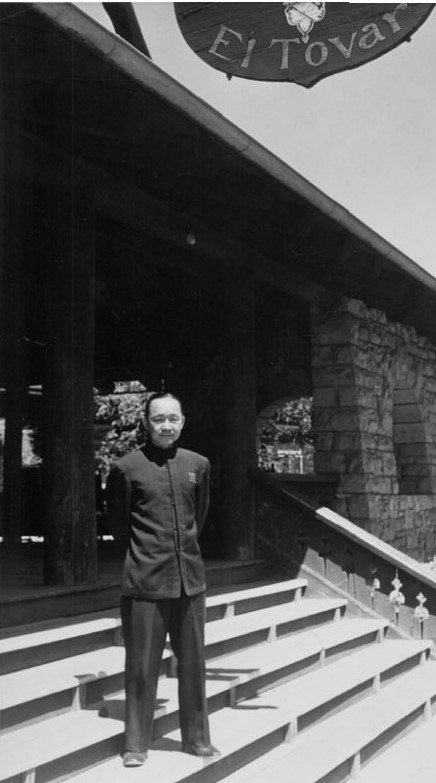

NPS / STEVE LEDING

George Murakami was a bellboy at El Tovar Hotel at Grand Canyon, a dedicated community member, and a WWII hero. Murakami was born in Hawaii and moved to California to work with the Los Angeles City Club. He saw the world while working on cruise ships and eventually made his way to the Grand Canyon in 1933. Though Murakami created a strong community at the canyon, he was also subjected to racially charged nicknames. When dealing with the broader public, Japanese Americans at the time were generally subjected to remarks of racism and fascination. The Fred Harvey Company leaned into the infantilization of Japanese people and culture at the time by only hiring Japanese Americans for bellboy positions. In the early 1900s it was seen as prestigious to have a Japanese individual in a position of service for a wealthy white person. The only people working as bellboys in 1940 were seven Japanese-American men. While many in the public had a fascination with Japanese culture, this often did not translate into care for the people themselves. This especially proved true after the start of WWII.

President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, which designated military zones where Japanese Americans would be forbidden. This resulted in the forced removal and incarceration of over 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from the Pacific Coast. Many of the confinement facilities were located throughout the Southwest. While the Grand Canyon did not fall into these designated military zones for forced removal, discrimination against Japanese Americans increased throughout the country. In 1941, the National Park Service requested that the Fred Harvey Company remove an “alien employee” from the canyon. The company moved the employee to another hotel they owned outside the canyon so that they would not have to terminate the employee.

None of the Japanese-American bellboys at Grand Canyon remained in their positions as of 1942. It is unclear where all went, but records show that George Murakami enlisted in the Army on March 13, 1942. Another Japanese American employee at Grand Canyon, Robert T. Kishi, enlisted in the army on August 25, 1943. He married his wife, a Grand Canyon Harvey Girl and member of the Hopi tribe, Josephine Navakuku, a week after he enlisted.

AMERICAN LEGION POST 42

George Murakami served in the 100th Infantry Battalion, part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. These units were completely made up of Japanese American soldiers. Murakami’s unit became highly decorated during the war and he was promoted to Staff Sergeant. He was awarded with a Bronze Star and an additional stripe to become a technical sergeant. He was discharged in November of 1945. While Murakami was able to safety return home, Robert Kishi was not so fortunate. Kishi belonged to Company G in the Second Battalion of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He served as a runner to deliver messages between units and was killed in battle while attending to the wounds of his comrades. Kishi was posthumously promoted to corporal and awarded a Silver Star for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy.”

George Murakami returned to Grand Canyon after his discharge and got his old job back. He also joined the local chapter of the American Legion, John Ivens Post 42. Murakami was elected by the other members to serve as sergeant at arms in four separate years. He served as post adjutant in 1948. In this year the chapter dedicated a memorial in the Grand Canyon South Rim Cemetery to those in the Canyon community who had died while serving in the World Wars. The monument features eight names, one being Robert T. Kishi. It is fair to assume that Murakami’s administrative role in the chapter that year helped to ensure that Kishi had his rightful place on the monument.

George Murakami continued to work at the Grand Canyon until 1965 when he moved to Los Angeles to work for the Fred Harvey Company at a restaurant in the Los Angeles Music Center. Murakami passed away in his Los Angeles apartment on June 15, 1982. Murakami left behind a legacy of 28 years of service and dedication to the Grand Canyon community.

For more information on Asian American History, please visit the Finding a Path Forward: Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks Theme Study

Sources:

Crable, Margaret. "Japanese Americans were forcibly imprisoned in camps during World War II. We finally know all their names." USCDornsife, September 26, 2022. https://dornsife.usc.edu/news/stories/names-of-japanese-americans-forcibly-imprisoned/.

Fried, Stephen. Appetite for America: Fred Harvey and the Business of Civilizing the Wild West--One Meal at a Time. New York: Bantam Books, 2010.

Hangan, Margaret. "Finding African American History in the West." KIVA: Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History 86, no. 2 (2020): 149-155. DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2020.1756096

Nuttall, Kern. “Why is a Japanese Name on the American Legion Memorial?” The Ol’ Pioneer: The Magazine of the Grand Canyon Historical Society 31, no. 1 (2020): 3-5. https://grandcanyonhistory.org/uploads/3/4/4/2/34422134/gchs_ol_pio_31-1.pdf.

Last updated: October 11, 2024