Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 14, No. 1, Spring 2022.

Article

How to Name a New Species from Badlands National Park

Ed Welsh

Badlands National Park, South Dakota

Every fossil tells a story, and this story details the discovery of a new carnivore from Badlands National Park.. It is often overwhelming to realize how much information can intertwine with one unassuming jaw fragment. Badlands National Park has an extensive and rich history of scientific exploration and discovery, which has always been worth studying and revisiting. Also, for readers unfamiliar with what can go into academic work, I wanted to intricately detail the plethora of information that goes from the field to the finished published work. Finally, the personal component involved with academic research is often overlooked. Friendly interpersonal connections are often expressed in minimal text within academic works. I wanted to share some of these professional connections of comradery and friendship that occur in collaboration and teamwork, and how scientists can honor their colleagues. One of my favorite quotes and philosophies comes from John Muir: “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.”

The first fossils from the White River Badlands, in what is now southwestern South Dakota, were documented in 1846. Countless studies have been published since then, making the White River Chronofauna one of the best documented fossil-producing areas in the world. After 175 years of scientific work, it is reasonable for anyone to develop a false sense of security towards a low likelihood of new discoveries being made. One assumption that can stem from this is expecting poor chances of finding a new taxon in these well-studied and well-collected strata, thinking everything has already been discovered and described. Another thought is, after so many expeditions and studies have been made, a certain area has been studied enough or might not be worth revisiting.

Those of us with a healthy amount of scientific paranoia know well that these are the best conditions to make new discoveries, in areas where others may have stopped paying close attention. Every scientist knows that science is never “complete” or “finished”, and often needs to be revisited. It’s easy to overlook details in an area where a plethora of knowledge seems to hide new opportunities for discovery. This paranoia definitely helped me in this case.

What is This Thing?

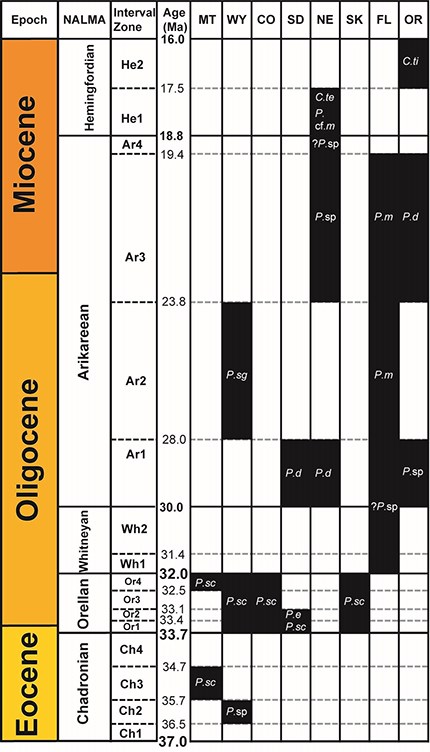

The specimen in question came from a small, linsang-like carnivore called Palaeogale. Palaeogale has an interesting history on its own, on top of being one of the rarest carnivores in any ecosystem it occupied. Palaeogale emerged in the latest Eocene, with the oldest fossils found in Montana and Wyoming. FYI, one of these sites in Wyoming is just outside of Yellowstone National Park. In the Oligocene and Miocene, Palaeogale is found throughout North America and Eurasia. North American sites are nearly restricted to the Great Plains (Colorado, Nebraska, Saskatchewan, South Dakota, and Wyoming), with the exception of Florida and a recent discovery at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon. In Eurasia, this animal has been found in China, France, Germany, and Mongolia. Wherever this animal appears, its fossils are incredibly rare and fragmentary. For example, only four specimens have ever been described in the South Dakota Badlands.

Palaeogale has also been confused for other animals. Originally, Palaeogale was thought to be a weasel (Family Mustelidae). Later, more detailed studies into Palaeogale’s anatomy revealed a closer affinity to Viverravidae, an extinct group of Paleocene and Eocene carnivores that might have looked similar to living linsangs, genets and civets (Feliformia) (also see National Fossil Day artwork for 2022). If any reader is unfamiliar with these animals, they look like weasels at a glance, but share a closer relationship to cats. A more recent phylogenetic study places Palaeogale at the base of Feliformia, just below linsangs, genets, and civets. This repositioning helped Palaeogale earn its own distinct family, Palaeogalidae. There are a handful of species within Palaeogale, and only four species had been reported in North America. Skulls of these animals are extremely rare. The number of described Palaeogale skulls has yet to exceed double digits. Because the jaws are more abundant, all species are defined by characters found in the jaws. If the reader would like to know more details about the species and ranges for North American Palaeogalidae, and who studied them, please consult the Introduction in Welsh (2021).

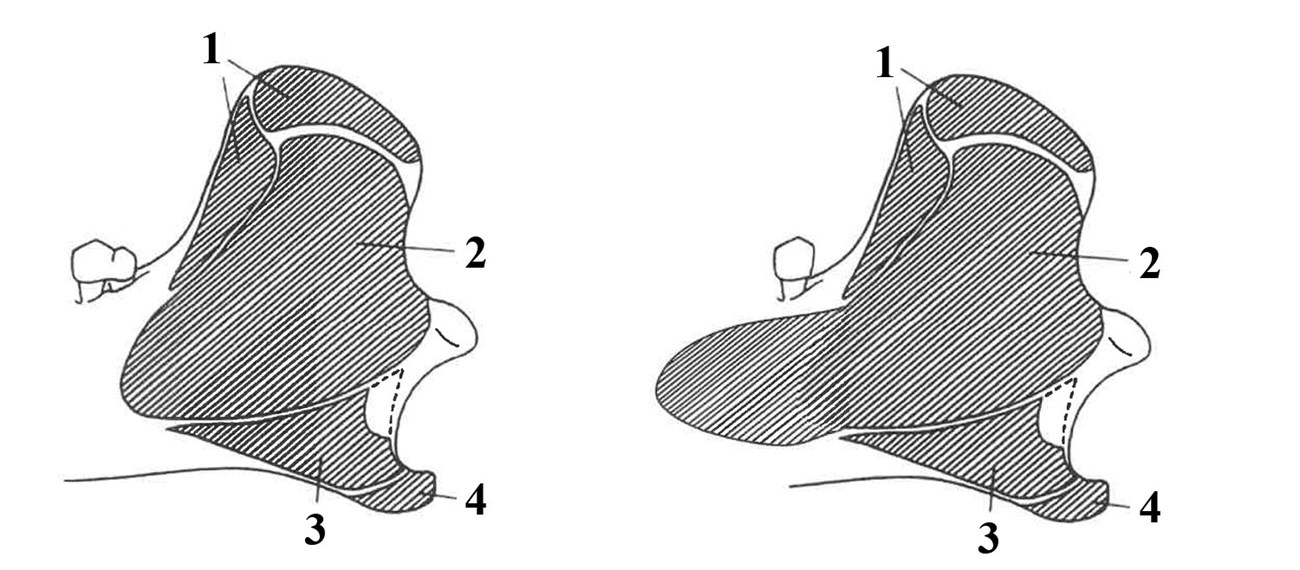

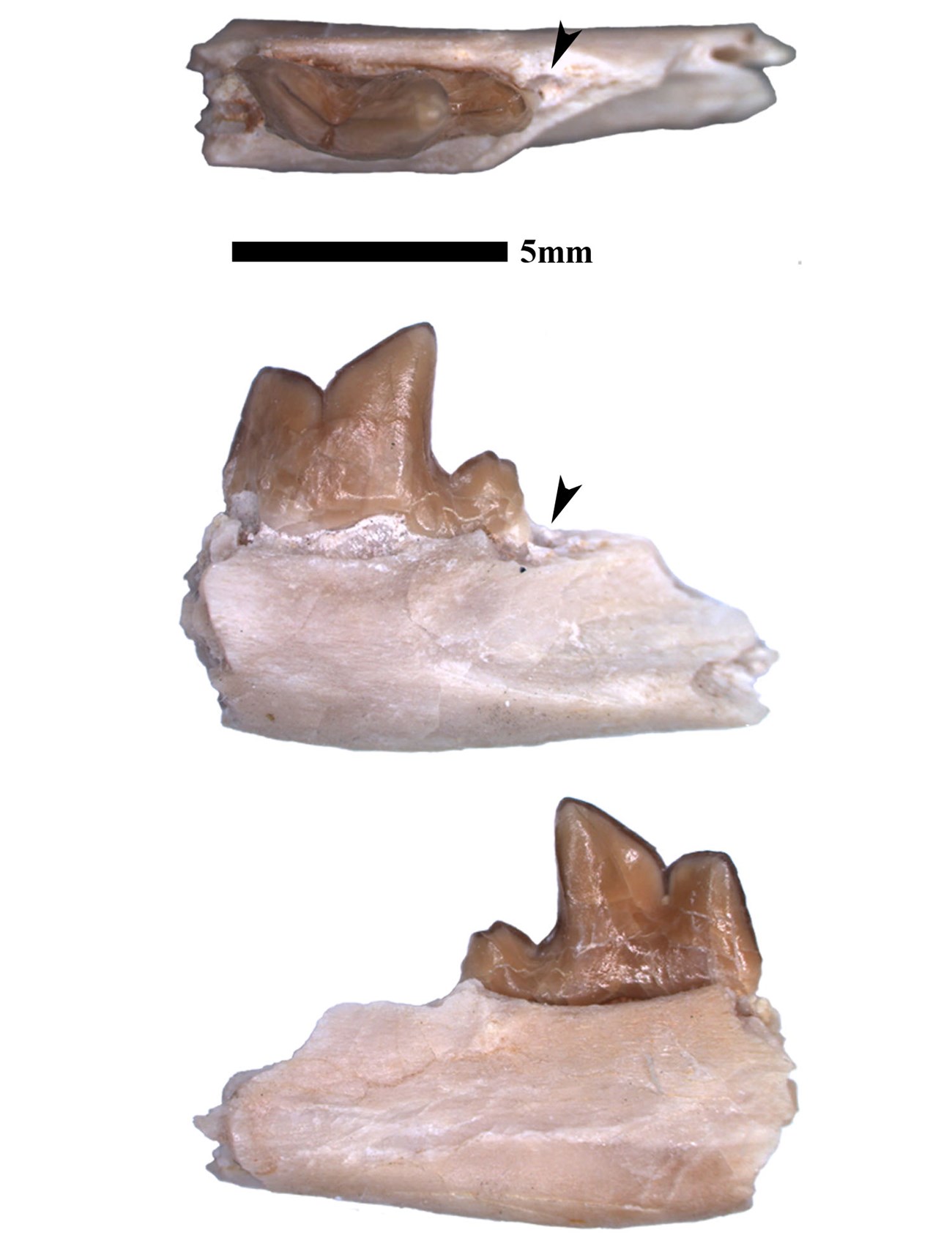

A jaw fragment that was recovered in a 2016 paleontology survey at Badlands National Park clearly belonged to the elusive Palaeogale. However, there were some peculiarities with the anatomy in this jaw. Every previously documented Palaeogale species has a double-rooted lower second molar, while this specimen only had one alveolus (tooth socket) for a single tooth root. The attachment area for the masseter muscle in the cheek is normally deep with a bony lip at the margin and angles downward at about 45º, increasing distance from the tooth row. This jaw had a shallow area for the masseter, and was horizontal while positioned close to the first molar. This was probably something different and new.

Line drawings comparing views of muscular insertions on the labial side of the mandible and m2 (modified from de Bonis, 1981) in P. sectoria (left) and BADL 64042 (right). Here, the anterior expansion of the intermedial masseter (2) is clearly visible. The presence of lower second molar and posterior dentary in the line drawing for BADL 64042 are extrapolated based on observable morphology. 1 = superficial temporalis, 2 = intermedial masseter, 3 = superficial masseter, 4 = medial pterygoidal.

I realized that I was looking at something potentially new, but I had to be careful. There was a chance this was something already discovered or some odd variation that someone else might have observed. I found nothing in the literature that fit the features I was observing. I spent as much time in museum collections as I could to find as many comparative specimens that existed. I visited my regular haunts at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in nearby Rapid City, South Dakota and the University of Nebraska in my home state of Nebraska. I was aware of other specimens from previous visits to the University of Colorado at Boulder, Colorado and with collaboration with a Ph.D. student from the University of Florida at Gainesville, who was doing field work in the White River badlands in Nebraska. I had to make a week-long visit to the American Museum of Natural History in New York to study a back-log of specimens for multiple pending research projects involving small carnivores. The American Museum also had specimens from Europe and Asia that I really needed to see. Thankfully, I was able to make my New York trip a couple of months before the SARS-COVID-19 pandemic reached the United States. I had found everything I needed to proceed with resolving this specimen.

Visit, Discover, and Repeat

Levi Moxness, a seasonal Physical Science Tech working in the Paleontology Department at Badlands National Park, found numerous interesting specimens during the 2016 summer field season. During survey, Levi discovered a gorgeous and nearly complete skeleton of Miniochoerus, which was embedded with another skeleton of the early dog Hesperocyon. He would also find the odd little jaw fragment that would eventually need a name. Even though Levi serendipitously found these sites, he was out here on survey with a particular purpose. Levi and other members of the paleo survey crew had a binder with copies of old photos from 1920–1922. Those photos were taken by Harold Wanless, who visited the Badlands on behalf of Princeton University. Some of these photos were in Levi’s survey area, and he was working on matching these old photos to locations.

Dr. Emmett Evanoff, from the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley, is a frequent visiting field researcher to Badlands National Park. It is very difficult to learn about Badlands geology and stratigraphy without coming across his name as an author. Emmett has also spent several years’ worth of effort studying the history of the early expeditions into the Badlands. He has been relocating travel routes, camp sites, and field sites going back to the fur-trade days, when people like Alexander and Thaddeus Culbertson (American Fur Trade Company) recovered the first fossils from the area in the 1840s. One major contribution of Emmett’s diligence has led to the relocation of significant sites and specimens. The early collections of fossils from the Big Badlands left a lot to be desired, especially in regards to detailed locality information, stratigraphy, and other data we cannot afford to take for granted in modern times. Among these historical pursuits was a pile of photographs from Harold Wanless, taken during his visits to the Badlands in 1920–1922. Emmett has become an expert in utilizing old photos to relocate field sites, and was drawn to Wanless’ numerous photos. Some of these photos were at fossil sites. So, Emmett approached his friends and colleagues at Badlands National Park, Rachel Benton, then the park’s paleontologist, and Ellen Starck, who was in charge of the paleontology survey that summer. He proposed that the paleo survey focus attention to areas where Wanless’ photos might have been taken, in hopes of relocating those sites. This proposal led to numerous successes, including being able to obtain important stratigraphic and geographic information associated with historically collected specimens. It’s not every day that a specimen that was named in the early 1920s can have pinpoint GPS data attached to it.

Photo taken by Harold R. Wanless, July 8, 1920.

NPS photo by Kathleen Brill.

Princeton University faculty and students made their first expedition to the Badlands in 1882 under William Berryman Scott. Scott began a decades-long tradition of field study in the Badlands. Harold Wanless was working on his Ph.D at Princeton University when he made his trips to the South Dakota Badlands in 1920–1922 as a student of William J. Sinclair. These trips led Sinclair and Wanless to publish invaluable research into refining understanding of the sedimentation and stratigraphy of the Badlands while incorporating correlative information on the fossil fauna. Aside from detailed geologic information and building a significant fossil collection, Wanless took copious photographs of their travels. These photos would provide invaluable information decades down the road. Approximately 120 of these photos were from locations within the current National Park boundaries. Badlands National Monument would not exist until 1939, but the idea of making the Big Badlands of South Dakota into a National Park Service site already existed. Senator Peter Norbeck had already introduced two bills to establish “Wonderland National Park”, and support for this legislation was reflected in an early South Dakota Geological and Natural History Survey report in 1922 (Ward and Toepelman, 1922).

So, What do I Call This Thing?

Often, the name of a species is chosen to honor a person or recognize a location. For example, the oreodont Merycoidodon culbertsonii, one of the first fossils Joseph Leidy (1848) described from the Badlands, was named after the collector, whose last name was Culbertson. The Cretaceous bivalve Inoceramus sagensis was named after Sage Creek, currently in the Sage Creek Wilderness Area in Badlands National Park. In other cases, the name is a short description of one of the creature’s physical features. For this species of Palaeogale, I considered the history of the area and the reason why the Badlands paleontology crew was out there. I came to the conclusion that the specimen should be named after Dr. Emmett Evanoff, because we likely would not have come across the specimen or the site if the crew wasn’t trying to relocate Wanless’ photo sites. I could have named it after Wanless, but Sinclair already named an entelodont after him, Archaeotherium wanlessi (Sinclair, 1922).

I wrote my description and sought out reviewers. I couldn’t have Emmett review, because I didn’t want him to know the animal was named after him until the paper came out. I went to Ellen Starck first, the current park paleontologist at Badlands, because she was familiar with the project and the study area. Vince Santucci, the NPS Senior Paleontologist, was eager to look it over as well. I reached out to Nick Famoso, the paleontologist at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, because he was simultaneously writing up newly discovered Palaeogale material from John Day. Andy Farke, at the Raymond Alf Museum in Los Angeles, California, has always provided me with thorough and thoughtful reviews. Lastly, I sought out Louis de Bonis, from the Université de Poitiers, Poitiers, France. Louis is the expert on Palaeogale, and has studied every specimen that was known to exist by 1981. If anyone could find a flaw in my assessment of this jaw belonging to a previously unknown species, it would be him. I chose to submit my research paper to the Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science. After one of the most rigorous series of review and edits I have experienced, I only had to elaborate on some of my interpretations. The editor and his reviewers approved the paper for publication, I registered the new species through ZooBank, and Palaeogale evanoffi was official as of early December, 2021.

Palaeogale evanoffi (BADL 64042)

What Did You Get for Christmas?

I was able to keep my scheme quiet enough that word never reached Emmett on this little carnivore being named in his honor. Emmett has been a great friend and colleague to the paleo staff here at Badlands, especially myself. It’s easy for Emmett and I to get into deep rabbit holes, discussing and musing on the nature of the badlands formations and how they tie with the evolution of ancient faunal landscapes. Most of what I understand about the area is due to Emmett. The paper was released on December 11th, about a week before it was originally scheduled, closer to Christmas. I reached Emmett’s wife, Kathy Brill, on the phone to let her know what I’ve been up to for the past year or so, including my scheme to name this animal after Emmett and reveal to him when it was official. She told me that my timing was perfect, because Emmett was having eye surgery the next day. I immediately sent her the manuscript to show Emmett later that afternoon. Ellen Starck mentioned to me that she wanted Kathy to record Emmett’s reaction when he found out, so I relayed and seconded that request. Later that evening, I get a call back from Emmett and Kathy. My response was, “Merry Christmas, Emmett!” Kathy gave me the rundown of Emmett’s reaction, which was about what I would have expected. While reading through the abstract, his commentary went from “…okay…” to “…okay…” with a sharp turn to “WHAT?!... WHAT?!” After all of that hard work, Emmett’s reaction is the achievement where my pride takes residence.

Emmett was pleased with the honor, but I think he is simply glad someone didn’t name an oreodont after him. I was more than happy to see this work through, with all of the help from people in the field, the museum curators, reviewers, and Emmett’s spouse. Without all of these people, or maybe they should be more aptly called co-conspirators, this scenario might not have played out so uniquely.

Further Reading

- Benton, R. C., D. O. Terry, E. Evanoff, and H. G. McDonald. 2015. The White River Badlands: geology and paleontology. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana.

- Bonis, L. de. 1981. Contribution a L’étude du genre Palaeogale Meyer (Mammalia, Carnivora). Annales de Paléontolgie (Vertébrés) 67(1):37–56.

- Famoso, N. A. and J. D. Orcutt. (in press). First occurrences of Palaeogale in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Geodiversitas.

- Stevens, J. S. and others. 2006. Discovery and re-discovery in the White River Badlands. Historic Resource Study, Badlands National Park, South Dakota. John Milner Associates, Inc., Renewable Technologies, Inc., and Bahr Vermeer & Haecker Architects, Ltd

- Toepelman, W. C. 1922. The Badlands as a National Park. South Dakota and Natural History Survey 11:75–86.

- Ward, F. 1922. The geology of a portion of the Badlands. South Dakota Geological and Natural History Survey Bulletin 11:1–80.

- Welsh, E. 2021. A New species of an enigmatic carnivore Palaeogale (Feliformia: Palaeogalidae) from Badlands National Park, South Dakota. Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science 100:107–120.

Related Links

- Badlands National Park, South Dakota—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home] [npshistory.com]

- Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home] [npshistory.com]

- NPS—Fossils and Paleontology

- NPS—Geology

Last updated: March 30, 2022