Part of a series of articles titled Home and Homelands Exhibition: Resistance.

Article

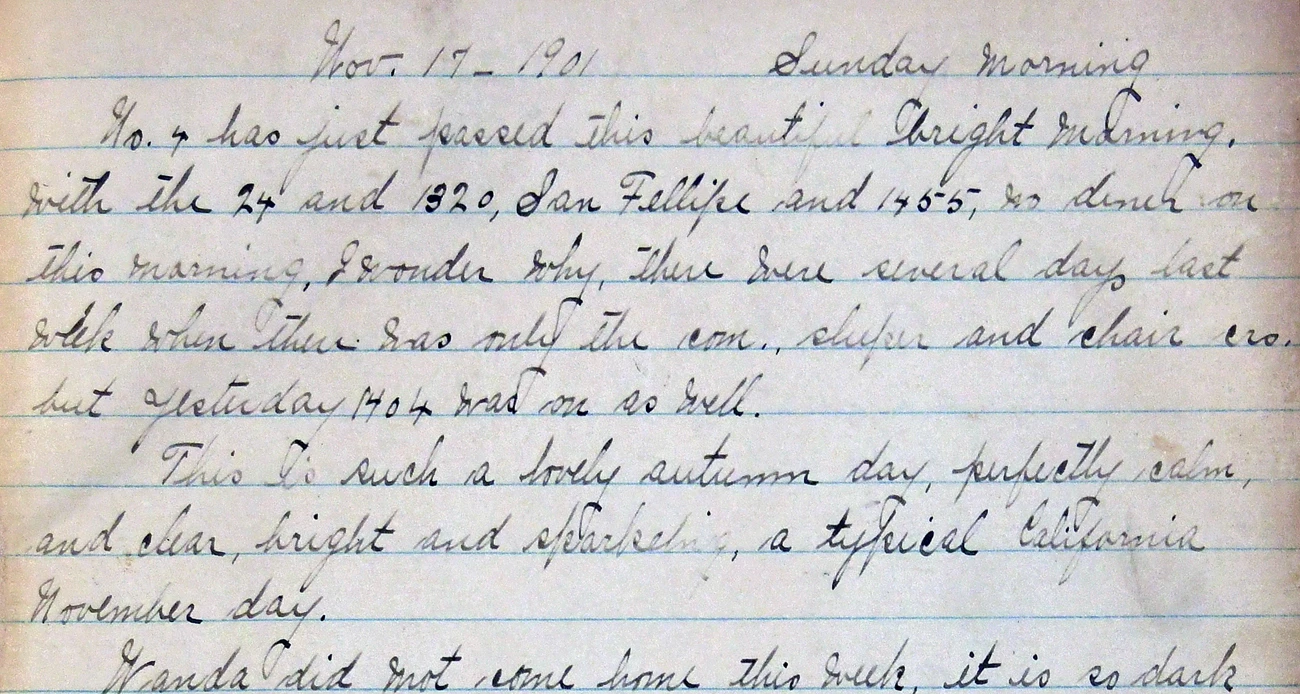

Helen Muir’s Diary

NPS Collections, JOMU 3583

Helen Muir was fifteen-years-old and utterly obsessed with trains when she began writing in her diary that covered the period from November 1901 through March 1902. Trains had long captured the American imagination as symbols of national progress and human ingenuity, but Helen’s detail-oriented infatuation went far beyond admiration. Plagued by pulmonary illness most of her life, she remained largely at home under the protective gaze of her famous father, naturalist John Muir.“No. 4 has just passed this beautiful bright morning. With the 24 and 1320, San Fellipe and 1455, no diner on this morning, I wonder why, there were several days last week when there was only the com. sleeper and chair crs. but yesterday 1404 was on as well.”1

-November 17, 1901

Not a Model Girl

Helen understood that her love for train engines did not fit conventional gender expectations at the turn of the century. In 1900, women had few political or economic rights and their primary expected societal role was domestic and maternal: to be a supportive wife and loving mother.4 Helen wrote that she was “not a model girl by any manner or means” unlike her “proper sister.” According to their father, Helen’s older sister was womanly, quiet, steady, and strong willed. Helen, on the other hand, was petite, amusing, smart, and unconventional. In other words, she was a lot like her father.5“My, but it does one good to watch a big beautiful locomotive coming towards you at a good rate of speed…if there is anything I love (and there is) it is to stand up just at one side of the track and watch an engine coming.”3

-January 8, 1902

Helen and her “dear Papa” were close. She loved taking walks with him, especially up the hill to the train station, and she helped him with his work. She also inherited her father’s obsession with how things work. Soon after turning “sweet sixteen,” she ordered three books that she believed “will teach me a great many things about an engine that I have long wanted to know.” Afraid the publisher would not send them to a girl, she used the name H.L. Muir.8

Helen also plastered her “railroadish room” with nearly thirty posters of locomotives and railroad maps. Delighted with the outcome, she wrote, “I guess there never was a girl who owned such a room as mine, I am perfectly satisfied with it, and think it is the loveliest girls room I ever saw any where.” In fact, she felt sorry for the “unfortunate girls” who lived in the city, not knowing anything about trains or engines.9

The Limits of Train Dreams

While Helen showed a remarkable degree of confidence and joy in her love of trains, she also had moments of doubt that limited her happiness. In one instance, she feared she was a “freak” for wanting to know so much about trains passing near her home. In another, she blamed her “stupidity” for not being able to understand valve motions from the books she ordered. She determined that her difficulty must be because she was “only a girl,” and later asked, “[I]sn't it too bad I am only a girl without any head, yet well supplied with the love of engines?”11“I was awakened at 7 o'clock this morning by one of the sweetest sounds I hear daily----The dear old 35's whistle, & it was perfectly lovely to wake with the tones in my ears, but after listening to her whistling up the canyon, I turned over again and snuggled down warm and ‘comfy’ under the cover and went to steep (sleep) again.”10

-January 14, 1902

A few years after the last entry in her diary, the Muir family suffered from a wave of pulmonary illnesses. Hit the hardest, Helen moved for the summer to the Arizona desert and never returned to the family home. The dry weather and freedom suited her. She eventually married and raised four children. She never became an engineer – or a writer, as her father hoped.13 Her teenage diary, however, captures an important period in her life, one in which home was physically confining but mentally expansive. It was a place where home was the sound of a train whistle that represented comfort and beauty but also mystery and possibility.

1 Helen Muir’s Diary Transcript, 1901-1902, November 17, 1901, 1, John Muir National Historic Site, JOMU 3583. This passage is the first entry in the diary.

2 Donald Worster, A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 387. Helen Muir’s Diary, January 29, 1902, 22-23.

3 Helen Muir’s Diary, January 8, 1902, 16.

4 For a volume exploring the nineteenth-century domestic ideal through primary sources, see Amy G. Richter, At Home in Nineteenth-Century America: A Documentary History (New York: New York University Press, 2015). For how some women broke free from familial restraints, see Joanne Meyorwitz, Women Adrift: Independent Wage Earners in Chicago, 1880-1930 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1988).

5 Helen Muir’s Diary, January 8 and February 27, 1902, 16, 33. Worster, A Passion for Nature, 386.

6 John Muir, The Mountains of California (New York: The Century Co., 1898, c. 1894), 79.

7 Worster, A Passion for Nature, 295, 388.

8 Helen Muir’s Diary, January 27, 1902, 21.

9 Ibid., January 8 and 11, 1902, 16, 18.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., February 19, 20, 22, 1902, 27, 28, 30.

12 Worster, A Passion for Nature, 386-87.

13 Ibid, 390-91, 395, 401.

Last updated: June 11, 2024