Last updated: January 15, 2026

Article

A History of Fort Warren

Boston Public Library

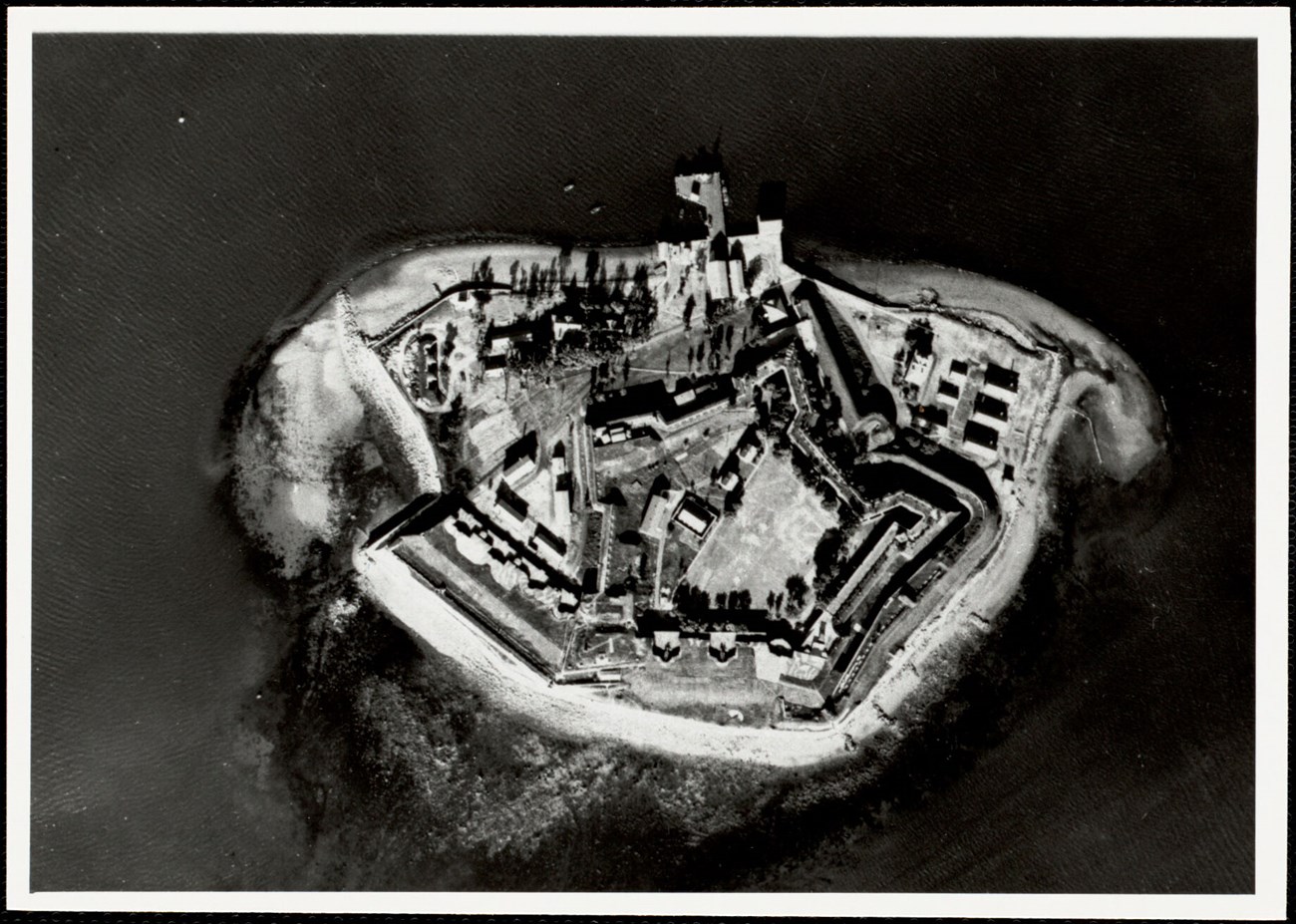

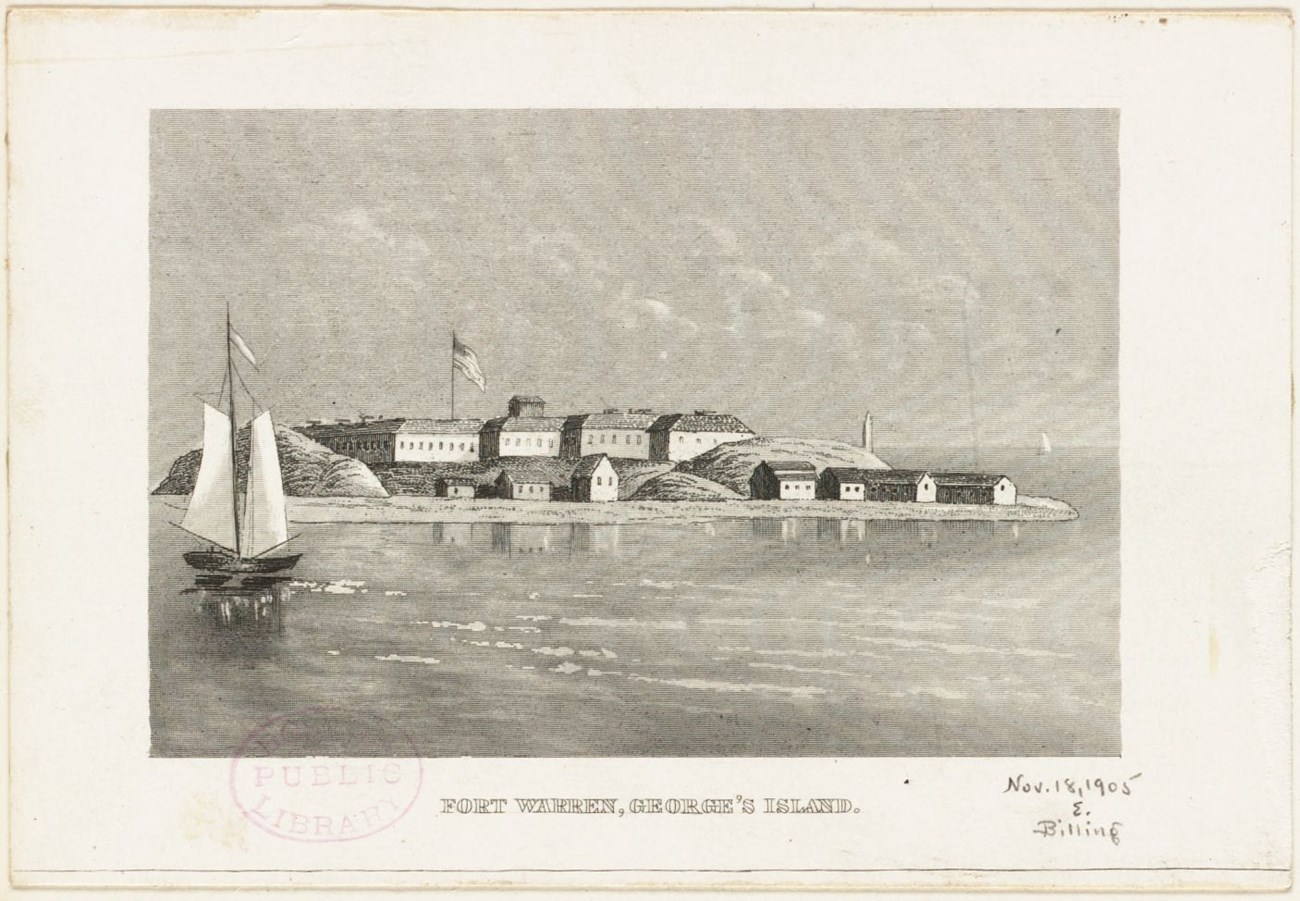

Seated on Georges Island at the entrance of Boston Harbor, the walls of Fort Warren protected the city of Boston from naval attack for one hundred years. The Fort is now on the National Register of Historic Places, and is open to visitors throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

Origins and Construction

During the War of 1812, the British Royal Navy effectively controlled much of the United States' coastline, including the eastern seaboard and gulf coast. With the end of the war in 1815, the defense of harbors and ports became a priority for the federal government. Spearheaded by President James Madison, the government enacted a program to update the US's coastal defense facilities, named the "Third System."

In 1820, the US Army began to draw up plans for a new fort on Georges Island in Boston Harbor. Five years later, the city of Boston purchased the island from its owner Caleb Rice, grandson of Revolutionary-era Loyalist Elisha Leavitt who had owned the island since 1765. Over the next few decades, the US Army Corps of Engineers started their preliminary work to prepare for the fort's construction. They built a seawall to prevent the island's erosion and by 1832 had surveyed the land on which the fortifications would stand.

Around this time, the project was named Fort Warren, in honor of Revolutionary War hero Joseph Warren, killed in action at Bunker Hill in 1775. The existing fortification on nearby Governors Island, which already bore the name Fort Warren, was renamed to Fort Winthrop instead.

Boston Public Library

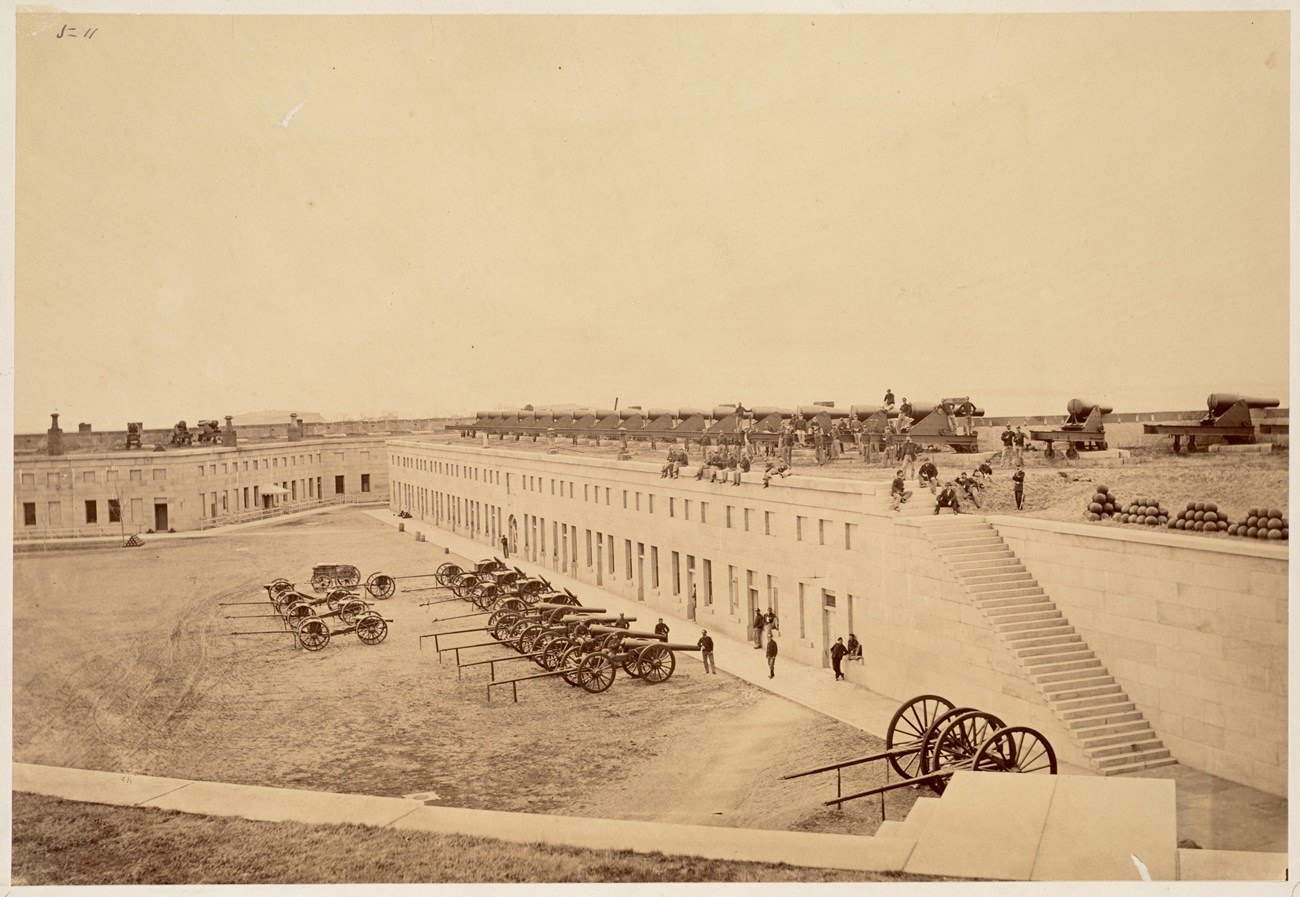

By the 1840s, the Army had begun construction on Fort Warren in earnest, using granite from nearby quarries in Quincy and Cape Ann to build its truly imposing fortifications. As James Lloyd Homer, a contemporary writer for the Boston Post, noted in 1845:

As far as the Fort is finished, it is probably the most magnificent piece of masonry in this or in any other country...the foundation walls of which are twelve feet thick, and the superstructure eight...The fronts are neatly hammered and the workmanship is as even and as perfect as it possibly can be.[1]

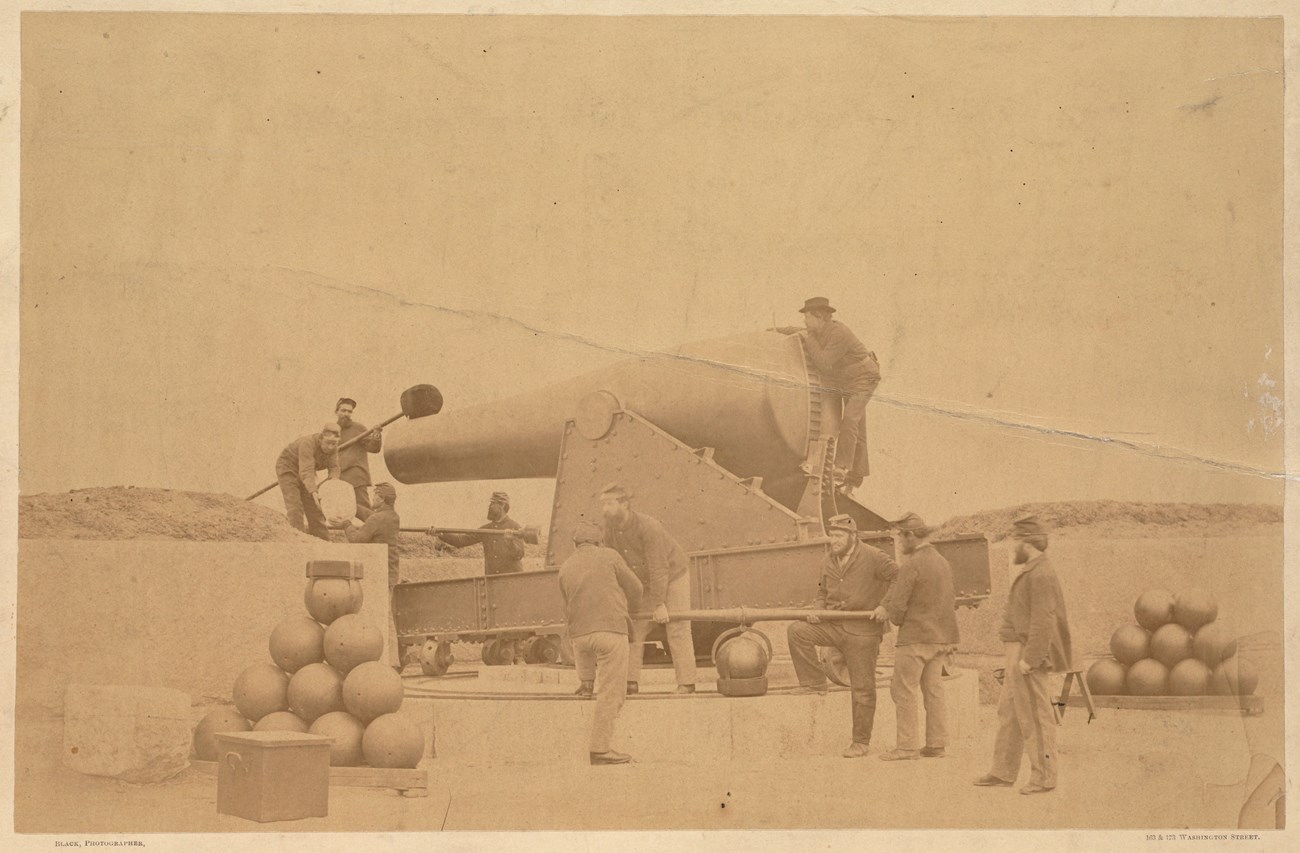

Although the thick stone walls of Fort Warren may have been imposing, its armament was not. As late as June 1848, Fort Warren was armed with only a single cannon mounted atop its walls. By 1850, Fort Warren was mostly finished, though the Corps of Engineers continued to work on the fortifications for the next decade.

Fort Warren in the Civil War

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861 kickstarted the American Civil War just as the construction of Fort Warren was nearing completion. For the first time in its history, Fort Warren was staffed by a garrison of troops: the 2nd Battalion of the Massachusetts militia. During their time at Fort Warren in May 1861, soldiers of the "Tiger Battalion" composed "John Brown's Body," a popular marching song that later evolved into the Unionist anthem "Battle Hymn of the Republic."

Throughout 1861, a number of Massachusetts volunteer regiments trained in and passed through Fort Warren on their way to the front lines in the South, including the 11th, 12th, 14th, 24th, and 32nd Infantry. A soldier's life at Fort Warren was not always comfortable. As Colonel Francis Jewett Parker of the 32nd Massachusetts wrote after the war,

Such duty on a bleak island, exposed to the terrible cold and storms of a New England winter, was no pastime. Occasionally some of the outposts would be untenable by reason of the dash of waves, and often inspection and relief of the posts was effected with great difficulty because of the icy condition of the ground. In the most severe storms the guard was replaced by patrols, each of two men, who walked the line, one patrol being despatched every fifteen or twenty minutes.[2]

James Wallace Black photograph. Boston Public Library.

In October of that year, Colonel Justin Dimick, a career US Army officer from before the war and former commander of Fort Monroe in Virginia, arrived to take command of Fort Warren. He held this position for most of the Civil War.

Over the course of the war, Fort Warren became a formidable defensive installation, tasked with protecting Boston Harbor from a potential Confederate naval attack. The garrison usually consisted of four companies of infantry, and by 1864 Fort Warren had 97 guns to defend its ramparts, a far cry from the single cannon it had sixteen years prior. Unable to acquire the necessary armament from the federal government, which needed every gun available on the front lines in the South, Governor Andrew resorted to filling the gaps with purchases from abroad.

Confederate Prison Camp

Around this time, Fort Warren began to serve as a prison camp for both Confederate prisoners of war and political prisoners. On October 31, the first prisoners arrived at Fort Warren: 155 political prisoners and over 600 Confederate soldiers. Although a greater number of prisoners than expected, Colonel Dimick and his staff worked hard to accommodate them. Under his leadership, Fort Warren became known as a tolerable, if not always comfortable, prison for those it held. Such was the Confederate prisoners' appreciation for Colonel Dimick that they gave his son, then serving with the 2nd US Artillery in Virginia, a letter requesting that he receive good treatment in case of capture by the Confederates. The younger Dimick was later killed in action at Chancellorsville in 1863.

Throughout the war, Fort Warren held over 2,300 prisoners within its walls, of whom only 13 died, a remarkably low percentage compared with other Civil War prison camps, north and south. Some prisoners tried to escape, the most dramatic instance being the August 1863 attempt by six officers and sailors of the recently-captured CSS Atlanta. Two drowned, two were caught in the attempt, and two officers made it as far as the Maine coastline before being recaptured. Not only southerners were held prisoner at Fort Warren during the war. Numerous US Army deserters were confined within its walls, and at least two Vermont soldiers were shot by firing squad.

Boston Public Library

Many famous names from the Confederate side of the Civil War passed through Fort Warren at one time or another, including Generals Richard S. Ewell, Isaac R. Trimble, John Gregg, Adam "Stovepipe" Johnson, Simon Bolivar Buckner Sr., and Lloyd Tilghman. Political prisoners included diplomats James Murray Mason and John Slidell from the Trent Affair, Confederate Postmaster General John H. Reagan, and writer Edward A. Pollard. However, the most infamous prisoner of them all was Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, held there beginning in May 1865. Stephens noted in his diary that:

I was alone, a coal fire was burning; a table and chair were in the centre; a narrow, iron, bunk-like bedstead with mattress and covering was in a corner. The floor was stone— large square blocks. The door was locked. For the first time in my life I had the full realization of being a prisoner.[3]

Nonetheless, Stephens was well-treated at Fort Warren. He enjoyed morning and evening walks around the grounds and had a good relationship with Major John W. M. Appleton, the fort's commander at the time.[4] Mabel Appleton, the Major's daughter, befriended Stephens and brought him flowers on multiple occasions.

The final Confederate prisoners were released early in 1866, and thus Fort Warren's service during the Civil War came to an end. It had not fulfilled its original purpose as a defensive fortification to protect Boston from a naval invasion, but its wartime service as both a camp for Confederate prisoners and as a training and staging ground for US troops proved invaluable. Hundreds of soldiers who staffed on Fort Warren's walls went on to fight in some of the war's crucial battles.

The Rest of the Century

After the Civil War, Fort Warren remained a key component of Boston Harbor's defenses. Even in peacetime, the soldiers were kept busy. From reveille at 15 minutes before sunrise to the sounding of taps at 9:15 at night, Fort Warren's troops performed guard duty and drill exercises, and ate their meals at regular intervals. In their spare time, the soldiers went hunting, fishing, and clamming on the island or visited the Fort's library, which contained several hundred books. They were allotted twelve hours of leave per week and one full day per month.

With the war over, the Army concentrated on improving Fort Warren's defenses to bring them up to date. This included replacing some of the elements of the Third System of fortifications with elements from the new Fourth System. The Army upgraded Bastions A and E and gradually replaced elements of traditional masonry with concrete and earthen structures.

However, the federal government's Endicott Board did not consider these improvements sufficient. Headed by Boston native William C. Endicott, President Grover Cleveland's Secretary of War, this commission made a detailed report on coastal defense installations around the United States. The Board found the forts in Boston Harbor to be especially deficient and in serious need of renovation.

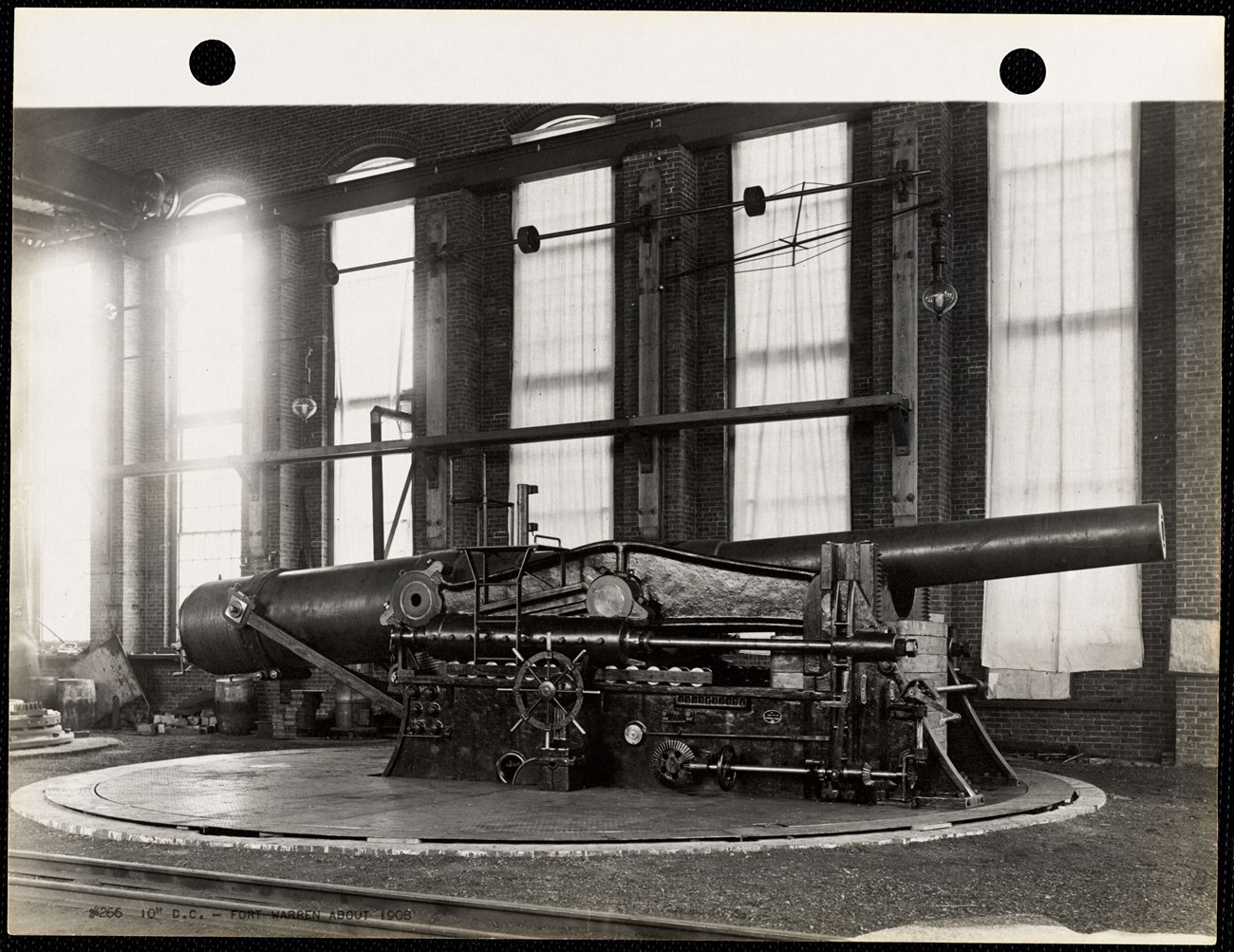

Over the next few decades, US Army engineers worked to bring the Boston Harbor island forts in line with the standards set by the Endicott Board. Fort Warren's improvements included the construction of five concrete gun batteries (Batteries Jack Adams, Bartlett, Plunkett, Lowell, and Stevenson, all named for Massachusetts Civil War heroes) and infrastructure for laying minefields in the nearby waters of the Narrows and Nantasket Roads. The installation of electrical generators for each battery brought Fort Warren into the modern age. Several of Fort Warren's guns were mounted on new disappearing carriages (DC), a military innovation that allowed guns to be raised and lowered at will, concealing them from outside view until they were ready to be fired at an enemy ship.

National Archives at Boston

In 1898, it seemed that Fort Warren's new defenses would finally be put to the test. In April of that year, after the explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, the United States declared war on Spain. Throughout April and May, reports that a large Spanish fleet was sailing north to bombard Boston sent the city into a panic, and the forts were placed on high alert. Fort Warren, with its complement of 10-inch, 8-inch, and 4-inch rifled guns and garrison from the 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, was prepared to meet this Spanish threat. However, no such fleet materialized, and the war ended with an armistice that August.

The turn of the century saw another round of renovations for Fort Warren. To apply the lessons of the Spanish-American War to America's coastal fortifications, President Theodore Roosevelt convened the Taft Board, headed by his Secretary of War (and future President) William Howard Taft in 1905. The Taft Board's recommendations placed great emphasis on the use of minefields, and so the already-existing mine casemate and mine storehouse were renovated. The power generators, soldiers' quarters, and hospital also received upgrades.

Fort Warren in the World Wars

In April 1917, the United States entered World War I with a declaration of war on Germany. Fort Warren was reactivated for service, and provided with a garrison from the 55th Artillery Regiment, Coast Artillery Corps. Raised for war service that year, the 55th consisted of eight companies with soldiers from the greater Boston area. By coincidence, some of the same militia units which garrisoned Fort Warren during the Civil War became part of the new regiment. A total of about 1,500 soldiers from the 55th Artillery garrisoned forts throughout Boston Harbor in case of German naval attack. In March 1918, the 55th Artillery received orders to prepare for deployment to France, where the regiment served in combat until the Armistice of November 1918.

Earle D. Wilson Collection, New Bedford Free Public Library.

Following World War I, Fort Warren reverted to peacetime status in 1919. The Fort lost its status as the headquarters for the Boston Harbor Island defenses in 1922, with the US Army relocating its headquarters to Fort Banks in Winthrop. 1928 saw Fort Warren placed on caretaker status, with only a minimum of personnel posted to the fort to maintain its upkeep. The staff consisted of two sergeants, two privates, and an engineer. In 1934, Fort Warren served as the headquarters for a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) effort to plant trees on the Harbor Islands. That spring, 40 CCC members quartered at the Fort sailed around Boston Harbor, planting an estimated 100,000 trees on the various islands.

By 1940, war was again raging in Europe. Even while maintaining neutrality, the United States began preparations for military action. The 241st Coast Artillery Regiment of the Massachusetts National Guard was placed in federal service that September, and the regiment performed a similar role as the 55th had in the previous war, providing much of the garrison for the various island forts. Joined by the 9th Coast Artillery Regiment from the Regular US Army, the 241st stood ready to protect Boston in case of German attack. Fort Warren's defenders concentrated on maintaining anti-submarine minefields in the Narrows and Nantasket Roads. .50 caliber machine guns and 37mm and 40mm anti-aircraft cannons provided defense against aerial attack. No longer suited to the new era of warfare, Batteries Bartlett and Stevenson were scrapped during the war.

In 1946, after the end of World War II, Fort Warren was once again deactivated, only to be reactivated the following year. The 1106th Service Unit garrisoned the Fort, performing maintenance on the mines. This short-lived posting ended in 1949, and Fort Warren played no part in the new Cold War. On December 31 of that year, the US Army declared that Fort Warren was no longer needed for defense and permanently deactivated. The formal disestablishment of the Coast Artillery Corps in 1950 brought an end to Fort Warren's century-long history of military service.

Photo by Matt Teuten

The Fort Today

The 1950s and 1960s were a period of flux and uncertainty for the Boston Harbor Islands. Private companies sought to use the islands for enterprises ranging from luxury resorts and golf courses to nuclear waste disposal. Georges Island was no exception, as the government sold it to a resort development company in 1957. Before any work could be done, however, the Massachusetts Metropolitan District Commission (MDC; now the Department of Conservation and Recreation) purchased Georges Island the following year. The MDC opened Fort Warren to the public in 1961, and the Fort has been a popular site for tourism and recreation ever since. In 1970, Georges Island became part of the Boston Harbor Islands State Park, and Fort Warren gained the status of National Historic Landmark the same year.

From the time of its creation in the wake of the War of 1812 up through the end of World War II, Fort Warren stood as the front line of defense for the city of Boston against an attack from the sea. Though its formidable defenses were never tested in battle, its importance to the United States’s national defense was significant. Many of the soldiers who garrisoned its fortifications went on to serve in combat, and some never returned. Fort Warren represents the history of American defensive military strength across a century, and today it is free for all to visit and learn about its history.

Footnotes

[1] Edward Rowe Snow, Historic Fort Warren (Boston Printing Company, 1941), 11.

[2] Francis J. Parker, The Story of the Thirty-second Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry: Whence it Came; Where it Went; What it Saw, and What it Did. (Boston: C.W. Calkins & Co, 1880), 6.

[3] Edward Rowe Snow, Historic Fort Warren (Boston Printing Company, 1941), 49.

[4] Before Appleton's posting to Fort Warren, Appleton had served as a captain in the famous African-American 54th Massachusetts Regiment and had fought at Fort Wagner.

Sources

Stokinger, William A. and Beth Jackendoff, Fort Warren George’s Island Fort Tour Background Package, Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation, 2008.

Snow, Edward Rowe, Historic Fort Warren, Boston Printing Company, 1941.