Last updated: January 15, 2026

Article

The Trent Affair

Library of Congress

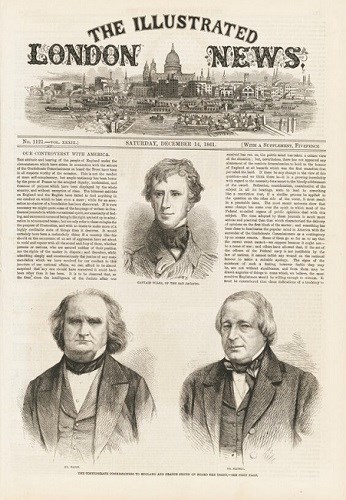

In November 1861, US Captain Charles Wilkes of USS San Jacinto captured a British mail ship RMS Trent carrying two Confederate envoys on their way to Europe. The two envoys had left the Confederacy through South Carolina, slipped through the US Naval blockade, and made it to Cuba, where Trent allowed them to board, fully aware of their diplomatic status. Designated as "Special Commissioners of the Confederate States of America," James Mason and John Slidell had been tasked with getting England and France to recognize the sovereignty of the Confederacy.

San Jacinto arrived in San Thomas on October 10, and Cuba not long after. Captain Wilkes became aware of the presence of the envoys through newspapers, and after hearing of their plan to leave on the Trent, he made a plan to intercept the vessel. The question of legality did not seem to have entered Captain Wilke’s mind, but he did inform Lieutenant Fairfax, his second in command, of his plan. Fairfax protested the plan and urged Wilkes to take caution not to cause an international incident.

Despite the protests of Lieutenant Fairfax, Wilkes took action on November 8. As Trent moved closer to where San Jacinto waited, a shell hit its bow, causing the vessel to stop. Although the British ship showed neutral colors, Wilkes boarded the vessel and forcibly removed James Mason and John Slidell. Wilkes allowed Trent to continue its voyage to England, while he set course to Fortress Monroe in Virginia.

Upon Wilke’s arrival at Fortress Monroe, he received celebratory praise for his actions and an order to take prisoners to Boston, where they arrived on November 24, 1861. Influential Bostonians threw Captain Wilkes and his officers a celebration at the Revere house. When Congress assembled that December, Mr. Lovejoy of Illinois made sure to thank Captain Wilkes for "for his brave, adroit and patriotic conduct in the arrest and deten- tion of the traitors, James M. Mason and John Slidell."[1]

At Fort Warren, a prisoner from North Carolina had been detailed to serve Mason and Slidell. They both received gifts from northern friends and ate well, much to the distress of some staunch Unionists, including Massachusetts Governor John Andrew. [2]

National Gallery

However, the incident was hardly resolved. The British government quickly determined the actions of Captain Wilkes had been illegal and requested both the immediate release of Mason and Slidell and an apology. France declared that if Britain went to war, it would support them. While the British maintained their neutrality, they ordered troops to Canada and ships to the Western Atlantic. The letter containing the British demands took almost an entire month to reach Washington D.C., and by that time the situation had cooled slightly. President Lincoln knew that beginning another conflict while already in one would not be a good move, famously saying "One war at a time."

On December 21, the cabinet voted to release Mason and Slidell.[3] In late December, British diplomat Lord Lyons received a letter that both defended the actions of Wilkes and acknowledged that he should have allowed a court to affirm the legality of the matter. Colonel Justin Dimick, Commander of Fort Warren, received orders to transfer Mason and Slidell into the custody of E.D. Webster of the State Department. A Boston newspaper reported that when Webster arrived to tell them of their departure, Slidell took as long as possible to pack up his stuff, though this incident is not noted in Mason’s account of the event.

Dimick escorted the former prisoners to a ship waiting to take them off Georges Island. Dimick refused to allow the other prisoners to leave as they left the grounds of Fort Warren.[4] After their release from Fort Warren, Mason and Slidell made their way to Europe to continue their mission, although they returned to Confederacy unsuccessful.[5] The release of Mason and Slidell in December of 1861 allowed the United States to narrowly avoid a war with Britain. Had they not been released, it is difficult to say how severe the consequences would have been for the United States, and the outcome of the US Civil War.

Footnotes:

[1] Charles Francis Adams, "The Trent Affair," The American Historical Review, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Apr. 1912), 542- 550.

[2] Shurcliff & Merill, Landscape Architects, History and Master Plan Georges Island and Fort Warren Boston (Boston: Metropolitan District Commission; Parks Division, 1960); Horne Mclein "Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War," (unpublished dissertation, 1955), 17,138.

[3] Margaret Gach,"TWE Remembers: The Trent Affair," last modified November 8, 2021, accessed April 23, 2023; Neil P. Chatelain, "The Trent Affair’s Diplomatic Winners and Losers," last modified November 8,2021, accessed April 23, 2023.

[4] Shurcliff & Merill, History and Master Plan Georges Island and Fort Warren Boston, 22; Minor Horne Mclein "Prison Conditions in Fort Warren, Boston, During the Civil War," (unpublished dissertation, 1955), 137-140; "The Trent Affair," History.com, last modified August 21, 2018, accessed April 23, 2023.

[5] History.com editors, “The Trent Affair,” last modified August 21, 2018, accessed April 23, 2023.