Last updated: January 14, 2025

Article

Historic Health in the Harbor

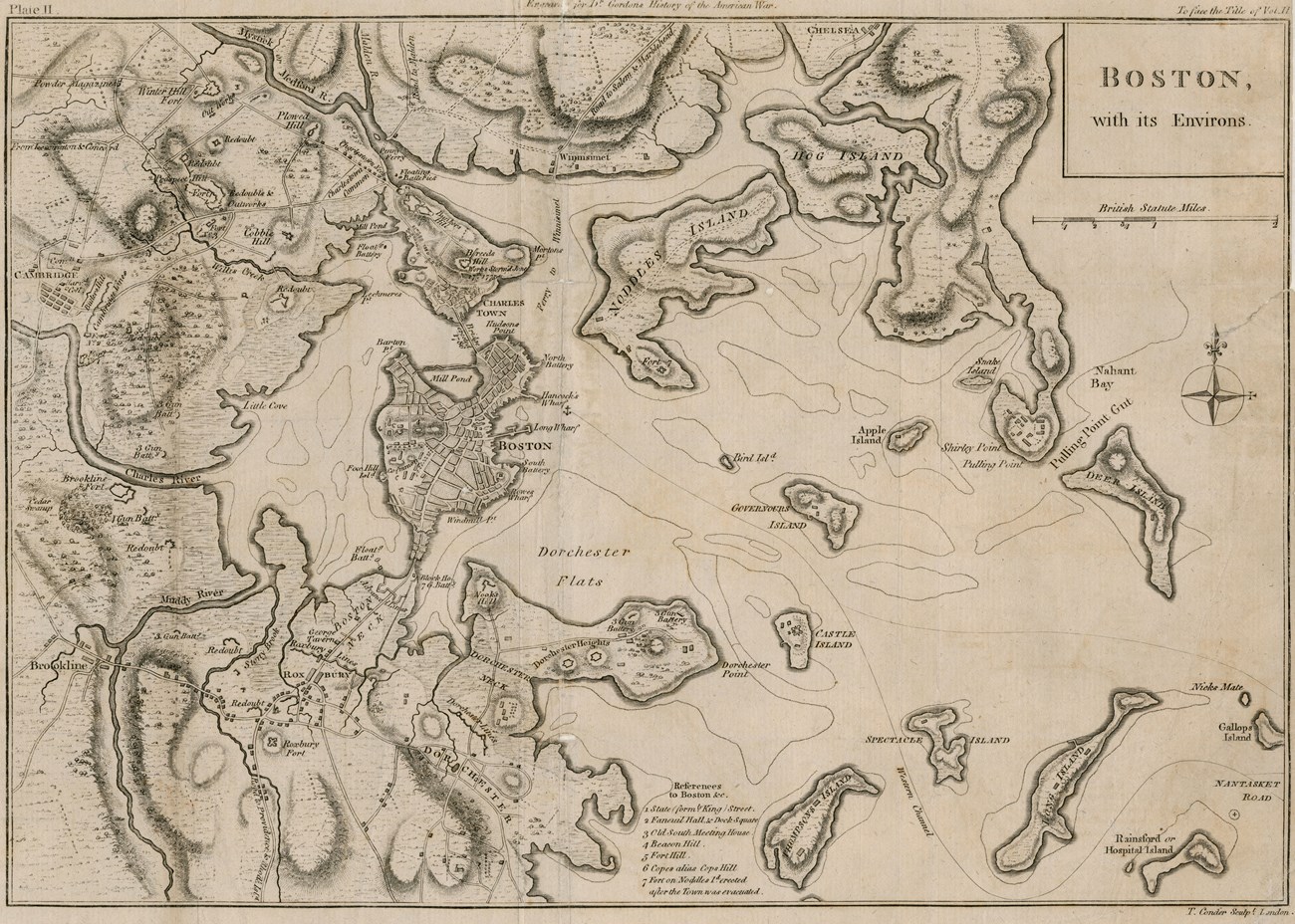

Thomas Conder, 1788. Boston Public Library

Since the time Europeans arrived and colonized what is now Massachusetts, at least seven of the 34 islands and peninsulas have been home to quarantine stations and hospitals. At best, these facilities achieved their intended roles of improving the health of those in need and keeping the public safe from disease. In some cases, however, these quarantine stations served as an avenue to outcast and displace unwanted members of society.

Quarantine Stations & Smallpox

Throughout the 1600s and 1700s, various smallpox epidemics swept through Boston. The Boston Harbor Islands provided partial solutions to Boston’s health problems as Massachusetts adopted temporary quarantine measures to prevent spread of communicable diseases. In 1677, Deer Island became the first quarantine station for passengers afflicted with smallpox traveling to Boston on inbound ships. Almost 10 years later, a sailing vessel carrying passengers exposed to smallpox was quarantined on Lovells Island. The Town of Boston opened another quarantine station on Spectacle Island in 1717. Many of those who arrived from Ireland during a 1729 smallpox outbreak were required to discharge crew and passengers there.

In 1737, Boston closed the station on Spectacle and purchased Rainsford Island, also known as Hospital Island, for a new quarantine station. In addition to serving the city, keepers of Boston Light and Castle Island were required to send all vessels carrying those afflicted with disease to Rainsford.[1] Inpatients at Rainsford faced poor conditions, with public health expert Fitzhugh Mullan saying of the Rainsford facilities:

It was the custom for Boston families to send their members [to Rainsford], when taken with infectious diseases…whence they were tolerably certain never to return.[2]

During the 1764 smallpox epidemic, Castle Island accommodated 3,000 patients. At some point, Dr. Joseph Warren opened an inoculation site on the island.[3]

Population density and mortality rates rose dramatically in the mid-1800s. During this time, many Irish immigrants were immigrating to Boston to escape the Potato Famine. Most ships did not carry a physician and diseases such as dysentery, cholera, and typhus spread rapidly. Due to a smallpox outbreak in 1847, a temporary quarantine hospital was built on Deer Island. Approximately 5,000 men, women, and children were admitted for treatment from 1847 to 1849. Although many recovered, more than 750 died and were buried on the island. The quarantine duties were eventually relocated to Gallops Island in 1866. By 1886, medical staff on the island were examining over 33,000 passengers per year.[4]

Island (and Floating) Hospitals

With the increase in population at the turn of the century, both city and state officials looked to the islands as places for social services. The Commonwealth purchased Rainsford in 1852, converting the quarantine stations into three almshouses and a hospital for the poor. Rainsford also had a home for Black Civil War veterans. Similar facilities - an almshouse and later hospital - were established by the City of Boston on Long Island.

Rainsford's facilities continued to bring in patients as conditions deteriorated and became intolerable. Through the efforts of Alice North Towne Lincoln, all operations on Rainsford ceased in 1894. The remaining inhabitants were transferred to Long Island, which continued operations as Long Island Hospital until 2015. Rainsford and Long Islands both have a complicated history in public health, as they served people in need while also removing some "less desirable" members from society. These islands likely served the inspiration for author Dennis Lehane's Shutter Island.

Tufts University

While facilities were established to house the poor and disadvantaged, concern for the wellbeing of children also increased. In 1894, Reverend Rufus B. Tobey started the Boston Floating Hospital. This hospital meant to combat high mortality rates due to heat by giving children exposure to the harbor breeze. The hospital took excursions through the summer, provided food, and assisted mothers with healthcare. Staff from the hospital also followed up with patients at home.

Industrialist, attorney, and philantropist Albert Burrage signed a lease for Bumpkin Island that went into effect in 1900 and planned to build a children's hospital. Doors opened in 1902, and the hospital included two open-air play areas and a pavilion. The hospital could accommodate up to 150 children with non-contagious diseases at a time whose parents could not provide "proper care."[5]

Public Health on the Islands Today

In recent history, Deer Island has taken on a new role in the city's public health. In 1995, the Deer Island Wastewater Treatment Plant began operation under the Massachusetts Water Resource Authority (MWRA). The sewage treatment plant has provided invaluable services in protecting Boston and its harbor from pollution, resulting in Boston's water being cleaner than its ever been.[6]

MWRA

Footnotes

[1] Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report: Boston Harbor Islands National & State Park, Volume 1: Historical Overview, (Boston: National Park Service, 2017) 140.

[2] Fitzhugh Mullan, Plagues and Politics: The Story of the United States Public Health Service (New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1989), 17. As quoted in Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 1: Historical Overview, 140-141.

[3] Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 1: Historical Overview, 85, 141.

[4] Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 1: Historical Overview, 140-142; Joe Mahoney, "Lasting Memorial in Boston to Forgotten Irish Famine Refugees," last modified May 19, 2019, accessed April 24, 2023; Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report: Boston Harbor Islands National & State Park, Volume 2: Existing Conditions, (Boston: National Park Service, 2017), 44.

[5] Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, Cultural Landscape Report, Volume 1: Historical Overview, 36-27, 144-145.

[6] Massachusetts Water Resource Authority, "Deer Island Wastewater Treatment Plant," date last modified September 2, 2009.