Last updated: July 6, 2023

Article

Hispanic Homesteaders and the Los Alamos National Laboratory

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Department of Energy

Homesteading in Los Alamos County

The Homestead Act of 1862 provided 160 acres of land to United States citizens who lived on, farmed, and improved the land for at least five years. Los Alamos County like much of the western United States was home to many homesteaders. Although people had been using the Pajarito Plataeu on a seasonal basis, homesteading originally began in March 1887 when Juan Louis Garcia filed for a homesteaded. The majority of the homesteaders on the plataeu were Hispanic.

Farming on the plateau was difficult because of the rugged terrain, high altitude (between 7,300 and 7,600 feet), short growing season, and lack of water. The homesteaders planted pinto beans and wheat as cash crops. Other crops included corn, squash, peas, pumpkins, potatoes, and kitchen vegetables. Sections of claimed land got smaller and smaller as all of the land suitable for farming was claimed.

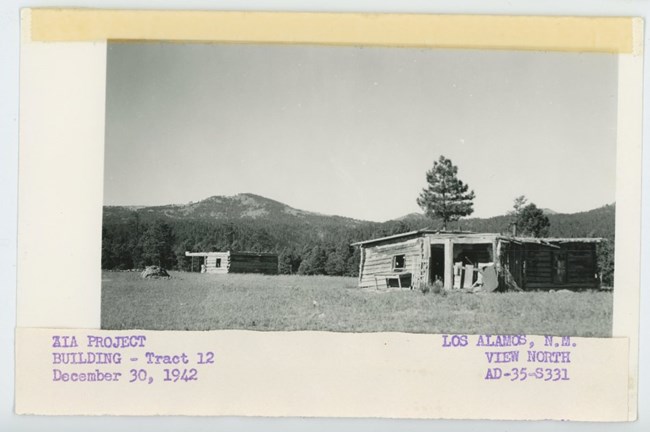

NPS/Feller

Of the 36 homesteads on the Pajarito Plateau, six were owned by Anglo families and thirty by Hispanic families. The Hispanic families generally lived on the plateau during the summer months moving to the Rio Grande valley during the winter.

When the army acquired the land on the plateau for the Los Alamos National Laboratory site in late 1942, 12 homesteads were still owned by the original owner and 7 more were still owned by the families.

Today only two structures from the homesteading era on the Pajarito Plateau remain: the Pond Cabin and Romero Cabin. The Romero cabin was relocated to downtown Los Alamos in 1984 and restored by the Los Alamos Historical Society. Victor and Refugio Romero built the cabin in 1912. Like many other Hispanic homesteaders, the Romeros and their six children lived in the cabin on the plateau from April to November and in the valley during the winter. The Romeros had a small 15 acre homestead where they planted corn, beans, and melons, and kept chickens, cows, pigs, and horses. The cabin had one room and was filled with homemade furniture and a cast-iron stove. The property also had a corral and grain shed.

Preparing for War

In August 1939, Albert Einstein wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt about fission and the potential of atomic energy for the upcoming war. Roosevelt responded by creating a committee of civilian and military representatives to study uranium.

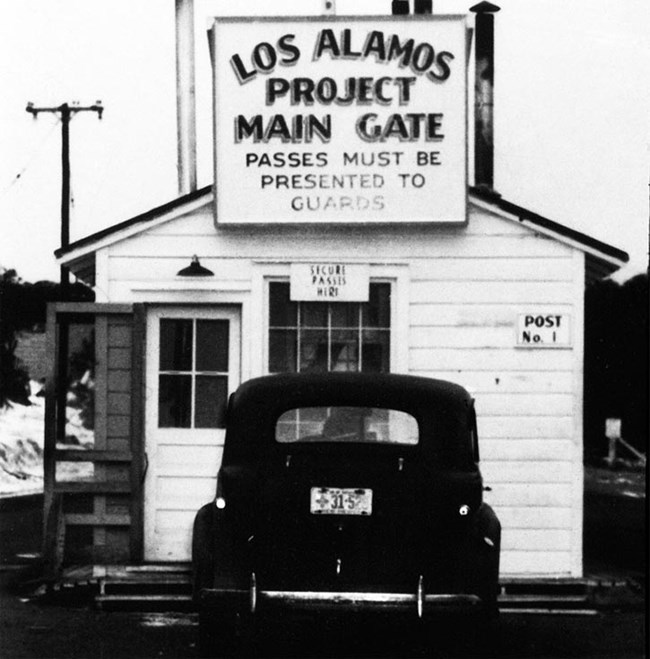

In December 1942, the government established the Manhattan Project to secretly research the use of atomic energy. To create such a powerful weapon they needed a facility and testing sites in a remote location. The Los Alamos National Laboratory was created for a sole purpose: to develop the atomic bomb.

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Department of Energy

Finding a Location

Secrecy was paramount for the laboratory, called Project Y, that would develop the first atomic bombs. The location needed to be large, sparsely populated, far from the coasts, and warm enough to continue work year round. However, it could not be completely isolated. It would depend on nearby power and water sources, as well as roads to transport materials and buildings to house the early personnel. They would have to take over an inhabited site to suit the needs of their project.

General Groves and J. Robert Oppeneimer decided that the laboratory would be located at a boy's school in Los Alamos County, New Mexico. The region was nestled in the plateaus of the national forest and surrounded by private property.

To engineer and conduct tests for the bomb, the government needed a large area of land, around 54,000 acres. Most of the land already belonged to the government as Forest Service land, but there was a community of homesteaders and two larger properties in the area to consider.

Henry Shadel, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

Bradbury Science Museum

Government Takeover

The Los Alamos Ranch School, established in 1918 by Ashley Pond, and the Anchor Ranch were the two largest properties in the area. The school provided college preparation and outdoor skills for young boys. Both entities were owned by Anglo entrepreneurs investing in the community. Both hired lawyers to negotiate deals with the government. The government paid $225 per acre for the school (including buildings) and $43 per acre for the ranch (land only).

Acquiring the land from the homesteaders was a different story. The official report states there were a few objections to the prices offered but most parties settled without any problems. The accounts of the homesteaders and their descendants tell a different story. They illustrate the difficultlies of the language barrier and their fear of the Army taking over their land.

What else could they do? Because they were frightened by these people in uniform. They came with guns and whatnot, and all of a sudden they came to them and they told them, “Well, you can’t come and plant anymore over here. We’re going to take over. The government wants your land." One of the things that was very hard for them to understand is that everything – maybe they wrote letters to them in English, but there was nobody to translate these letters for them.

~Rosario Martinez Fiorillo, descendant of homesteaders evicted by the Manhattan Project

The Hispanic homesteaders received between $7 to $23 an acre from the government, a huge contrast from the school and ranch. Some families said they were forced off their property by gunpoint and some were not given the amount the government initially offered them and ended up a recieving a lower payment.

Repatriation

Nearly 60 years after the loss of their property, many of the homesteaders and their descendants demanded reparations and acknowledgement of the unfair treatment. The descendants filed two separate lawsuits for justice in 2000. The group split into two factions, one pursuing 2,500 acres of undeveloped land though the court and the other asking for monetary compensation through Congress. With the support of New Mexico Senators Pete Domenici and Jeff Bingaman, Congress authorized a $10 million program to settle the lawsuits. In 2004, The Pajarito Plateau Homesteaders Compensation Fund was approved by Congress as part of the Defense Authorization Bill 2005.

The government acknowledged that the Hispanic homesteaders were not paid as much for their property as others were and that they did not have legal representation. In addition to the monetary settlements, the U.S. Department of Energy agreed to fund a book on the history of homesteading on the Pajarito Plateau. Homesteading on the Pajarito Plateau, 1887-1942 was released in 2012. Authors Judith Machen, Ellen McGehee, and Dorothy Hoard extensively researched the plateau homesteads and the families who worked them.

Additional Resources

A Tale of Two Homesteaders: Contrasts between the Harold Brook and Victor Romero Homesteads presentation by Judy Machen at the Los Alamos Historical SocietyCivilian Displacement: Los Alamos, NM | Atomic Heritage Foundation

Department of Energy (DOE) OpenNet documents (osti.gov) Manhattan District History. Check out Book VIII: Los Alamos Project (Y)

Homestead Tour (losalamoshistory.org)

Manhattan Project Voices Oral Histories of Manhattan project workers, families, and descendants of homesteaders

Tags

- homestead national historical park

- manhattan project national historical park

- manhattan project

- homestead act of 1862

- homesteader

- new mexico

- world war ii

- latino american history

- hispanic american history

- hispanic heritage month

- los alamos

- stories of los alamos

- hispanics and the manhattan project

- people of los alamos

- latino

- latino heritage

- migration and immigration