Last updated: January 7, 2023

Article

Going in Circles: A Revolution Along the Blackstone

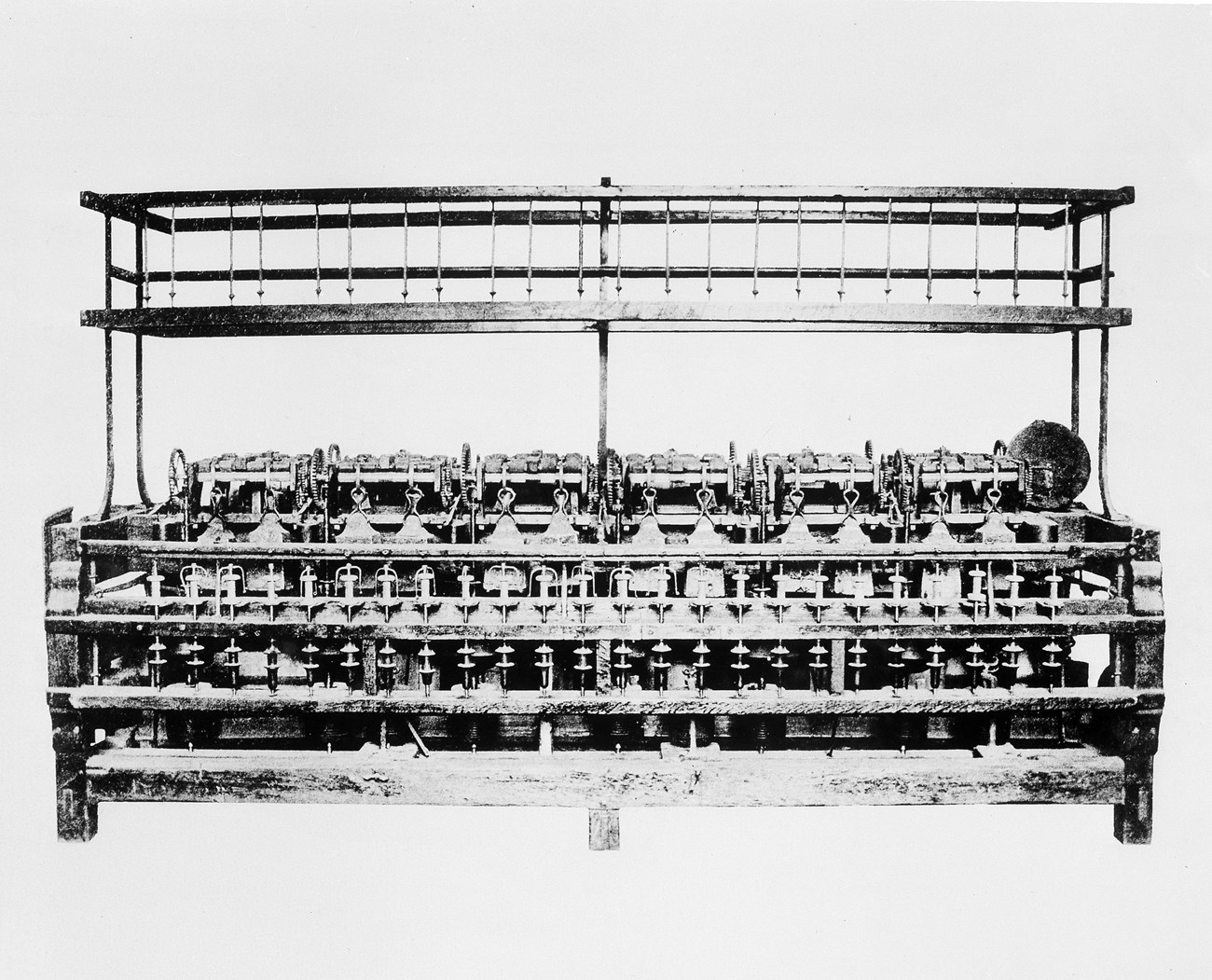

Winning a war of independence was only the beginning. Mere months after the Constitution of the United States went into effect, a second revolution began. This one would not start with a declaration, but it would be launched with the opening of a mill. This mill introduced a new way to transform cotton into thread. In 1789, an aspiring industrialist from Belper, England disembarked a ship in New York. What he did next set into a motion a series of events that fundamentally changed how people lived and worked. We still deal with some of the consequences of these choices today.

Samuel Slater left his home in England after completing a lengthy apprenticeship. Born in 1768, Slater was trained for work in the cotton spinning industry. Slater worked in textiles from the age of 14 until his death in 1835. For several years, Slater worked in a factory run by Jedediah Strutt in Milford, England. That training period ended in August 1789. The following month, he was on a ship headed to the Americas.

Slater arrived in New York late in November 1789. He came looking for opportunity. If Slater had stayed in England, he could have worked within family businesses or made his way through his connection to the Strutts. He could have made a comfortable living. But there was a limit to his ambitions. Slater must have sensed that more was possible in the United States.

In January 1790, Slater came to Rhode Island, where an investor named Moses Brown was willing to take a chance on an unknown machine maker. Over the next three and a half years, Slater, Brown, and a number of investors and craftspeople worked together to make a cotton spinning mill. This process truly took a village, and it was not a singular accomplishment.

Between 1790 and 1793, Slater’s main task was to work with local laborers to build machines that could spin cotton into thread. He also prepared his workforce for a new type of labor. Slater’s workers were children, most around ten years of age. The idea of children working was not unusual in the 1790s. Working for a stranger, in a new type of mill, for pay, was something new for these Americans. The amount of turnover and conflict recorded in Slater’s logbooks and letters reveals that this was not a smooth transition for anyone.

Unlike the people of Pawtucket, Slater was familiar with how factories ran in England. By age 21, Slater had spent a third of his life among mill workers. The craftspeople and farmers he encountered in the United States, people who’d recently fought a war for freedom, were not accustomed to the more rigid ways of factory work. Slater’s mill offered people living nearby a new way to earn money. The child laborers he hired did not get to enjoy the fruits of their labor. Few gave serious thought to the rights of free children as independent beings. Wages went directly to parents.

Slater came of age in an era of Revolutions. This may partially explain why he took the chance to make a name for himself in a foreign land. In Rhode Island, Slater settled among people just learning to live with the Revolution. Along with the people of Pawtucket, Slater was just starting to realize what separating from the British Empire might mean. Should Slater succeed, he could accrue a tremendous amount of wealth, away from the watchful eyes of the Strutts and other established English factory owners. If he failed, this would be yet another setback in the creation of a strong manufacturing system in the United States.

For decades, it had been customary for people in the colonies to buy finished products, including cloth, from Great Britain. In the introduction to the first major biography of Samuel Slater, author George White explains, “It has always been the well known policy of that powerful nation, to supply her colonies with the home manufactures.” People in the United States lacked the technology to make their own cloth, and the reliance on English-manufactured goods continued for decades. The ability to use a machine to spin cotton into thread was an important first step in breaking away from the powerful English textiles industry. White explains, “if the manufacturing establishments are in reality a benefit and blessing to the Union…the name of Slater must ever be held in grateful remembrance by the American people.”

Slater arrived in the newly formed United States at a pivotal moment. Some merchants felt an acute need to fully break away from Great Britain by forging a new path in manufacturing. Not all Americans in this era agreed. President Thomas Jefferson argued that one class of free people ought to be supported by enslaved labor, living on large tracts of land. The idea of trading one’s time, and often, one’s opportunity to own land, to earn a living felt like too great a sacrifice.

The people who worked for Slater traded their time and sometimes traded their health for a steady income. Children who grew up working in mills could suffer life-altering injuries that would make finding other kinds of work difficult. For some, working in a mill also meant not learning another trade that might suit them better in the long term.

Slater and others would expand their mill operations by creating mill villages. In these places, entire families worked for pay in and around mills. Living in one of these communities meant forfeiting one’s right to fully participate in democracy. In Rhode Island, only a small number of people could vote to begin with, and owning land was one provision. By moving to a mill village, men lost an essential right to engage in democracy.

What’s more, factory work was not open to all in Rhode Island or Massachusetts. Though enslaved labor was essential to the harvesting of cotton in the United States and throughout the British empire, enslaved people were not brought in to work in mills. Nor were recently liberated African American people hired to do work at Slater’s mill once operations were fully underway. Black craftspeople worked to build the mill and worked on various machines prior to July 1793. However, they were not regular employees, nor were their children hired by Slater.

Conditions for Black laborers, free and unfree, had been changing around the time of Slater’s arrival. In 1784, Rhode Island passed the Gradual Emancipation Act. After declaring their independence from Great Britain, some colonists had been reluctant to free the people they owned, usually enslaved African Americans. When Slater arrived in 1790, approximately 20% of African Americans in Rhode Island were still held in bondage due to the provision that emancipation did not need to be immediate. Right up until Slater’s death in 1835, some people in Rhode Island were still not free.

Slater’s investor, Moses Brown, had been part of a Rhode Island campaign to end slavery. However, Brown himself had personally invested in the slave trade and continued to profit from slavery by trading in cotton from plantations grounded in slave labor. Slater’s Mill was economically tied to slavery from the start.

What did freedom mean to the first generation of industrial mill workers in the United States?

Starting in 1793, with the opening of Samuel Slater’s mill in Pawtucket, RI, a new type of work took root in New England. Adults in these communities rarely regarded the rights of children, whether those children were related to them or in their employ. Yet even the “freedom” to earn a wage was not extended to everyone, as many Americans were shut out of the mill system altogether. Slater’s admiring biographer suggested that he might be “held in grateful remembrance”—but only “if” the industrial revolution can be thought of as beneficial to the people of the United States. We might ask what benefit the factories served for the children whose lives were dictated by the whims of factory owners ringing bells, for the people whose lives were disrupted by the rise of mills and dams that polluted their waterways, or for the Indigenous peoples whose lands were claimed and renamed in the pursuit of “progress.”

Those who lived through the early years of the Industrial Revolution didn’t know it. What they knew was the turning of gears and wheels and the rush of the waterpower systems that made their revolutions each day. The people who inherited the American Revolution came into this era of industry on unequal terms. Some would earn a wage for the first time. Others lost some of their rights by choosing the relative security of mill work, as opposed to the feast and famine of farming. A revolution can refer to an overthrow, a major social change. It can also mean a single, complete orbit. The root word, revolvere, means to ‘roll back.’ For all the new things wrought by Slater, he also brought about a curious kind of revolution. Slater took a fully English way of doing business, of running factories and workers’ lives, and brought it to a place where people desperately sought to break free from Great Britain.