Last updated: April 29, 2021

Article

Gardening for Wildlife with Native Plants

Courtesy Ted White

Native plant gardening is a fantastic way to enjoy some national park-style nature observation without ever leaving your yard, and a great way to partner with the National Park Service in preserving biodiversity.

Gardening can be fun, good exercise, and many people find it gratifying to build something and see (and maybe taste) the results of their labors. Some of the things that draw people to our national parks stimulate people to work in the dirt: human curiosity and love of nature, enjoyment of the outdoors, a sense of peace or tranquility, and gardens are wonderful classrooms for children of all ages.

Courtesy Ted White

Why Native Plants?

Small birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish depend on insects for a significant portion of their diet. A baby bluebird for example relies on its mother to deliver bugs to the nest. Those bugs in turn depend on plants to transform the energy of the sun into something edible. Plants use an array of poisonous or nasty-tasting chemical defenses to avoid being consumed, so most insects have evolved specialized relationships with specific plants, tolerating and even benefitting from those chemicals.

It takes millennia for specialized insect-plant relationships to develop. A well-known example is the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and milkweed (Asclepias spp.). Monarch mothers only lay eggs on milkweed species because monarch caterpillars have evolved the ability over tens of thousands of years to digest poisonous milkweed leaves other insects cannot eat. Replacing milkweed with day lilies for example, or another introduced plant, and expecting monarchs to evolve the ability to eat that instead is like expecting your cat or dog to suddenly evolve wings and fly. Adaptation in nature takes time.

Introduced plant species contribute almost nothing to the food web. Much of the exotic greenery we see in our residential areas provides as much nutrition as concrete or asphalt. The most visible example: replacement of native plants with 40 million acres of turf nationwide has led to a significant amount of habitat loss over the last couple centuries of our history.

Courtesy Ted White

Rebuilding Biodiversity

The good news is it’s reversible: even a small number of native plants makes a visible difference. Restoring native species to your property generates rapid results in terms of the number and diversity of wildlife you see. Plant it and they will come!

Courtesy Ted White

Plant a Park! Your Adventure Awaits

People go to national parks for adventure, beauty, relaxation, and the sense of wonder of visiting a pristine natural area. Planting a tiny “national park” in your yard can bring those benefits home for you and your family to enjoy year-round. If Americans were to replace only half their lawns with native plants, we could build a 20-million-acre network of habitat!

Courtesy Ted White

Case Study: One Park Ranger’s Story

Ted White is a park ranger who’s worked in Arizona, New Mexico, Massachusetts, California, and Washington, DC. He and his spouse purchased a home in suburban Maryland in 2014 when their first child was born. As a ranger and steward to some of the nation’s most treasured natural resources, White was interested in restoring some of their 1/6-acre property to a natural state as a traffic-free means for the growing family to experience nature.

The Idea

White drew initial motivation from childhood experiences learning about plants and visiting national parks with his father, and as with many people, gardening was a way of remembering and connecting with a parent now gone. He was also inspired by the work of a biologist couple he’d met in California who’d restored their suburban property in Lawndale with dramatic results. They’d made it look easy and fun.

Courtesy Ted White

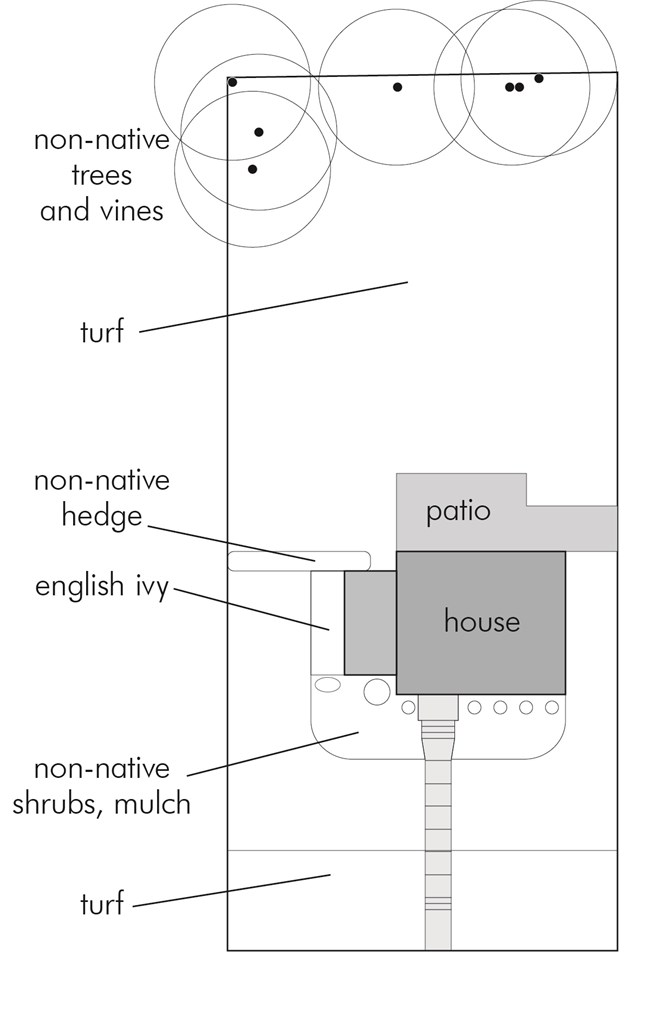

The Yard

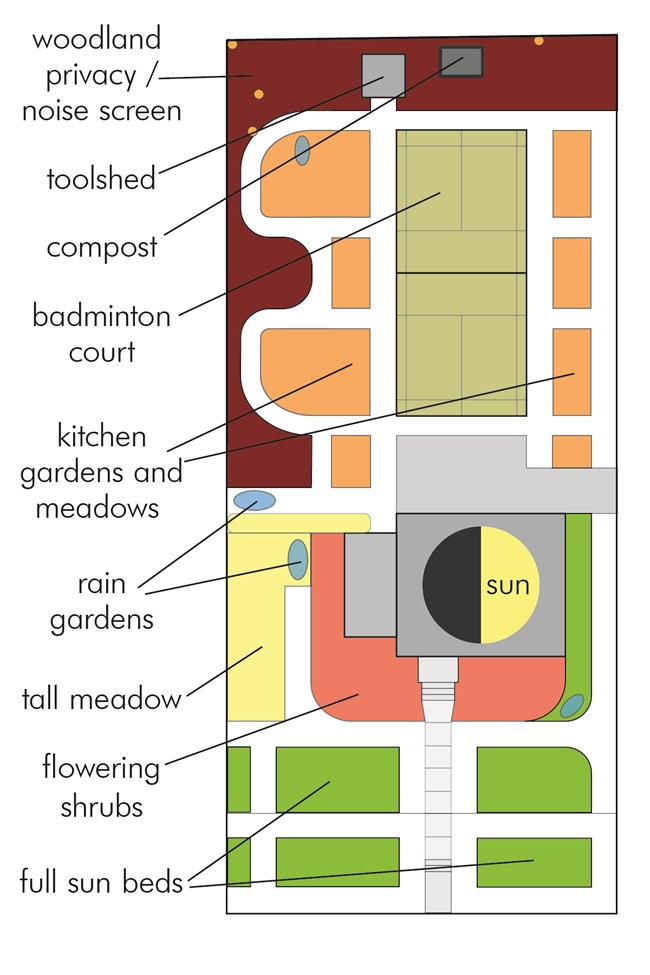

The property was almost entirely turf with a handful of introduced trees, shrubs and vines. The first summer after moving in, the Whites saw little more than mosquitos flying around their yard. Starting from scratch, White removed invasive species, and over the next four years, re-introduced over one hundred species of plants native to the mid-Atlantic Piedmont.

Bees and butterflies returned immediately, and biodiversity increased steadily. During the summer of 2019, White observed 17 species of native butterflies and 22 species of native birds. White now has a daughter as well, and says, “Every day we go outside we see something new. The kids have shown me bugs I’ve never seen before, and I grew up in the Northeast.”

NPS / Ted White

Making a Plan

“What should I plant?” is probably the most frequently asked question for beginning native plant gardeners. Here are twelve general steps to help you get started:

1. Your Yard is Your Refuge

Consider how you want to use your yard. Do you have children? A dog? Do you like to sit outside? Play sports? Your yard is habitat for you, so make sure your gardening doesn’t conflict with your household wishes and needs.

2. Know Your Yard

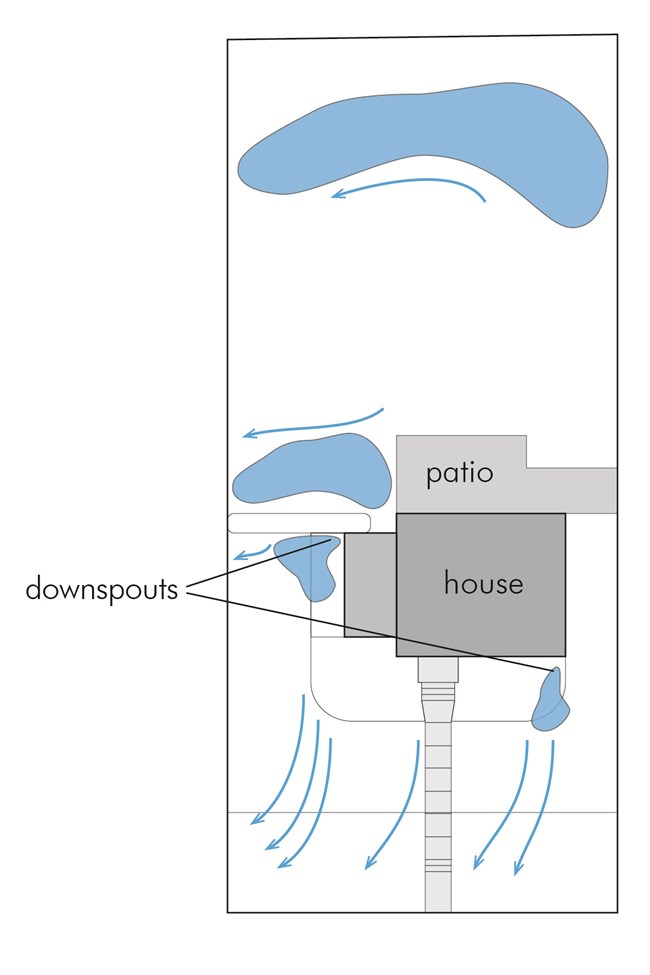

Document existing conditions. Have fun learning what’s already growing: use a service like iNaturalist to get the whole family involved in citizen science! Watch and see where the rain goes when it falls. What areas have sun versus shade? What kind of soil do you have? What’s under the ground? Make a map. You can use online satellite mapping and digital illustration tools. You can also use pencil and paper. Local university extension services and native plant societies are two other great resources for learning to identify local plants.

NPS / Ted White

3. Experience Your America

Find out what belongs and does not belong by getting to know your local ecoregion. Then you can narrow your list to the most appropriate plants for your area. The Pollinator Partnership has developed 32 region-specific planting guides. Our national parks and public lands are great resources, as they showcase functioning ecosystems. Visit Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area to learn what grows naturally in the Los Angeles area, or Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area to see some of the native flora of the Southeast, to name two examples. In addition, numerous state and local parks actively teach visitors about the native plants of their specific area.

4. Zip Code Matters

Use a service like the National Wildlife Federation or Audubon Society plant finders, which produce lists of native plants suitable for your area. The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center lists native plants by state. Develop lists of local plants that benefit wildlife, and decide what is most appropriate for your yard.

5. Conditional Love

Double check plants you like against your site conditions. The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center is also an excellent nation-wide one-stop-shop for learning about native plant characteristics such as requirements for light, moisture, and soil, how big a plant gets, when it blooms, what color the flowers or foliage will be, and what wildlife benefit from it. Your local area or native plant society may have even more detailed resources.

NPS / Ted White

6. Think 3D

Consider the different layers of vertical space in nature, looking to fill your yard in a visually attractive manner, and fill niches that might otherwise be occupied by invasive plant species:

a. Canopy

b. Understory

c. High Shrubs

d. Low Shrubs

e. High Plants

f. Low Plants

g. Ephemerals

h. Ground Cover

i. Vines

j. Root Zone

7. Picture This

Sketch out a plan. Consider: recreational space; privacy; how you want things to look; what blooms when; growth habits; space for walkways; hardscape features; curb appeal. Get creative! Make different versions! The overall framework of your plan will keep you on course.

8. Slay Dragons

Remove harmful introduced plants. Check state and local resources for more information. Work safely and get help if you need it!

Courtesy Ted White

9. Brown is Beautiful

Dead flower stalks and leaves serve as winter habitat for numerous insects in their larval stages. If you’re getting rid of an introduced tree, consider girdling it and leaving part of the trunk standing. You will be amazed at what shows up!

10. Prioritize!

Think long term. You might want to add big things like trees and shrubs first if you have space for those, bearing in mind once your tree grows to 8o feet, you won’t want it over gas or water lines, next to wires, or right next to your house or driveway. If you have trouble with weeds, consider species that can hold ground. Think about which butterflies, bees, beetles, and beneficial wasps and flies you want to invite to your yard, and plant accordingly. They will come!

11. Share with the Neighbors

Build your gardening community. Your neighbors can be a fantastic resource you never knew about. It is helpful to join forces with other like-minded stewards to share knowledge, experiences, plants and seeds! The difference in beauty and biodiversity in your yard will likely inspire others.

12. Sit Back and Savor

Enjoy watching the wildlife that shows up in your yard! Restoring biodiversity to your property is one of the quickest ways to relish the fruits of your labors. As with most things, the fun increases exponentially when you learn from, share with, and teach others. Plant a Park!

Courtesy Ted White

Making a Difference

The National Park Service protects some of the remaining pristine natural areas in this country. However, a look at the National Park System map shows that our national parks are a widely spread chain of small islands. Parks by themselves are inadequate to protecting the great variety of species the food web requires. In order to accomplish the National Park Service Mission and protect biodiversity, we need your help. Restoring native plant species to your yard helps build valuable habitat and connectivity. It can make the difference in ensuring bugs, birds, and other wildlife have the sustenance they need to survive in the future.

Treating your yard like a “miniature national park” makes you and your family fellow caretakers of national treasures and teaches new generations and old to value nature. Your yard can be a place transformed, not just a yard, but a valuable piece of real estate that supports a diversity of life.